The Works of

THOMAS CARLYLE

(1795-1881)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2014

Version 1

The Works of

THOMAS CARLYLE

By Delphi Classics, 2014

The Translations

Carlyles birthplace at Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire, Scotland

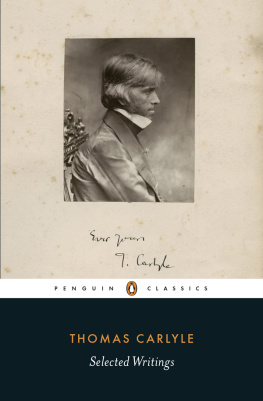

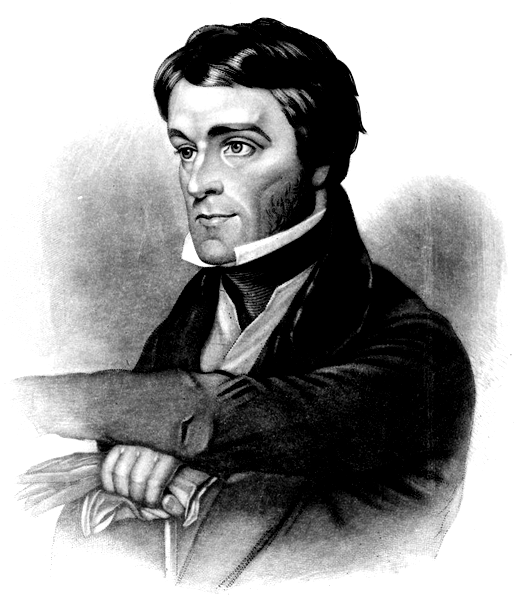

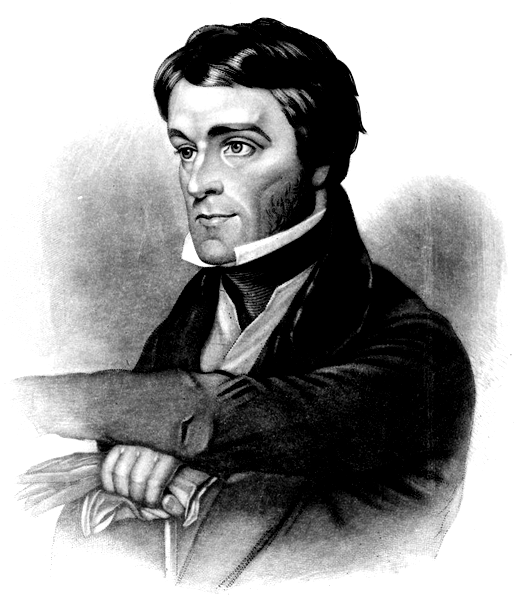

Carlyle as a young man, 1839

Carlyles wife, Jane Welsh Carlyle (1801-1866), a noted letter-writer and her husbands intellectual collaborator

WILHELM MEISTERS APPRENTICESHIP

This is a translation of the famous German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethes novel, Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (1795-96). Goethes novel pioneered the bildungsroman (a novel detailing an individuals education and development), which had a lasting influence on many major Victorian novelists, such as Charlotte Bront , William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens. It centres on the protagonists journey of self-discovery as he seeks to escape the emptiness of his life as a bourgeois businessman. In particular, it details Wilhelms discovery of Shakespearean drama, his newly-discovered love for the theatre and his dealings with the mysterious Tower Society.

Carlyles translation appeared in 1824. By this point in his career, Carlyle had attended Edinburgh University and been a mathematics teacher, but had given that up in order to write on a permanent basis. This was one of many German translations which he produced early in his writing career. He was introduced to German literature through a reading of Madame de Stals Germany , but the works of Goethe and the philosopher Friedrich Schiller would have the most influence on Carlyles later work and thought.

Title page of the original three-volume edition

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), whom Carlyle venerated and whose works he translated

CONTENTS

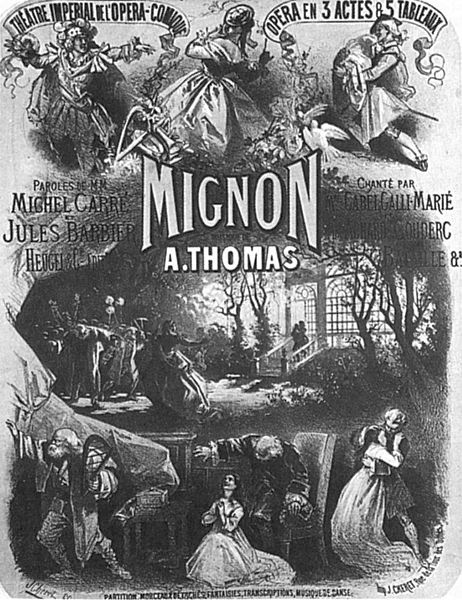

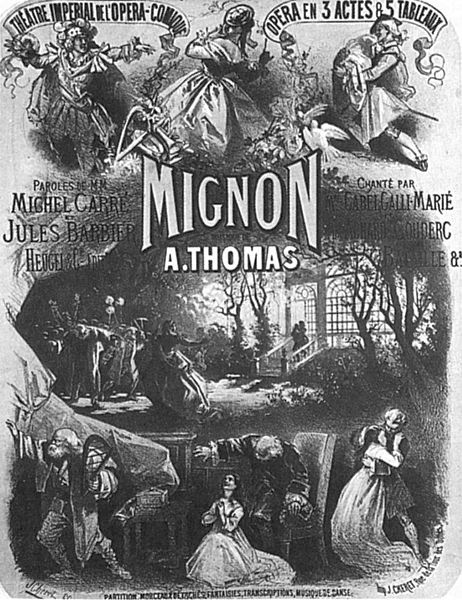

Mignon, an opra comique by Ambroise Thomas, which was inspired by Goethes second novel

Goethe, close to the time of publication

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

Whether it be that the quantity of genius among ourselves and the French, and the number of works more lasting than brass produced by it, have of late been so considerable as to make us independent of additional supplies; or that, in our ancient aristocracy of intellect, we disdain to be assisted by the Germans, whom, by a species of second sight, we have discovered, before knowing any thing about them, to be a tumid, dreaming, extravagant, insane race of mortals, certain it is, that hitherto our literary intercourse with that nation has been very slight and precarious. After a brief period of not too judicious cordiality, the acquaintance on our part was altogether dropped: nor, in the few years since we partially resumed it, have our feelings of affection or esteem been materially increased. Our translators are unfortunate in their selection or execution, or the public is tasteless and absurd in its demands; for, with scarcely more than one or two exceptions, the best works of Germany have lain neglected, or worse than neglected: and the Germans are yet utterly unknown to us. Kotzebue still lives in our minds as the representative of a nation that despises him; Schiller is chiefly known to us by the monstrous production of his boyhood; and Klopstock by a hacked and mangled image of his Messiah, in which a beautiful poem is distorted into a theosophic rhapsody, and the brother of Virgil and Racine ranks little higher than the author of Meditations among the Tombs.

But of all these people there is none that has been more unjustly dealt with than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. For half a century the admiration we might almost say the idol of his countrymen, to us he is still a stranger. His name, long echoed and re-echoed through reviews and magazines, has become familiar to our ears; but it is a sound and nothing more: it excites no definite idea in almost any mind. To such as know him by the faint and garbled version of his Werther, Goethe figures as a sort of poetic Heraclitus; some woe-begone hypochondriac, whose eyes are overflowing with perpetual tears, whose long life has been spent in melting into ecstasy at the sight of waterfalls and clouds, and the moral sublime, or dissolving into hysterical wailings over hapless love-stories, and the miseries of human life. They are not aware that Goethe smiles at this performance of his youth, or that the German Werther, with all his faults, is a very different person from his English namesake; that his Sorrows are in the original recorded in a tone of strength and sarcastic emphasis, of which the other offers no vestige, and intermingled with touches of powerful thought, glimpses of a philosophy deep as it is bitter, which our sagacious translator has seen proper wholly to omit. Others, again, who have fallen in with Retschs Outlines and the extracts from Faust, consider Goethe as a wild mystic, a dealer in demonology and osteology, who draws attention by the aid of skeletons and evil spirits, whose excellence it is to be extravagant, whose chief aim it is to do what no one but himself has tried. The tyro in German may tell us that the charm of Faust is altogether unconnected with its preternatural import; that the work delineates the fate of human enthusiasm struggling against doubts and errors from within, against scepticism, contempt, and selfishness from without; and that the witch-craft and magic, intended merely as a shadowy frame for so complex and mysterious a picture of the moral world and the human soul, are introduced for the purpose, not so much of being trembled at as laughed at. The voice of the tyro is not listened to; our indolence takes part with our ignorance; Faust continues to be called a monster; and Goethe is regarded as a man of some genius, which he has perverted to produce all manner of misfashioned prodigies, things false, abortive, formless, Gorgons and hydras, and chimeras dire.

Next page