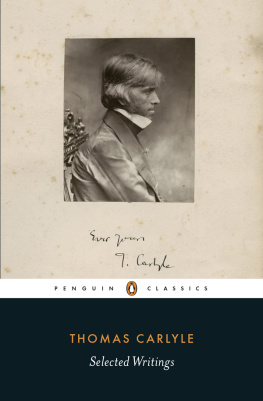

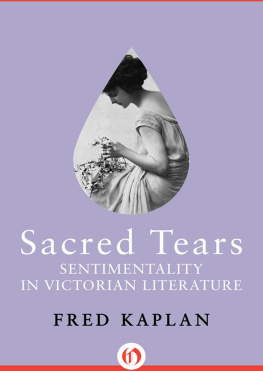

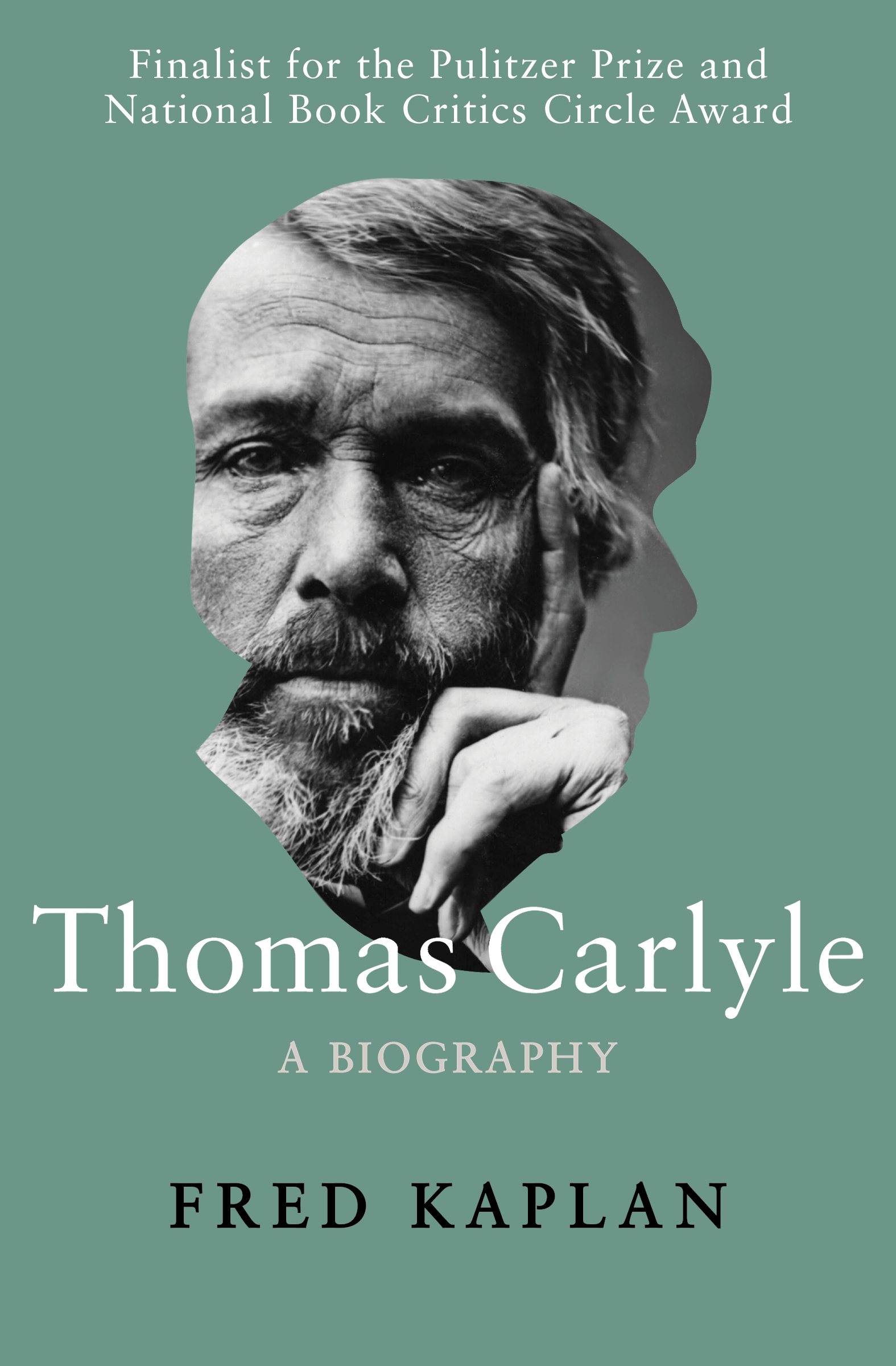

Thomas Carlyle

A Biography

Fred Kaplan

To Gloria

[1]

The Pursuer

17951816

In the quiet twilight the hoarse cawing of the rooks over Ecclefechan filled the young boy with sensations of mystery and beauty. The birds circled and returned to the Hill of Woodcockair two miles away, mysterious to me as the home of the rooks I saw flying overhead. Ecclefechan in southwestern Scotland was the spot on earth his feelings and imagination most identified with throughout his life. Deeply a man of place, he hated wanderers and wandering, the nomadic obsession. In his mind and in his words he strained always to reproduce the movement of the rooks whose great circles gave form to mystery and established boundaries to the place he called home.

Born on December 4, 1795, in the Arched House, Ecclefechan, a building designed and constructed by his father and uncle, Thomas Carlyle soon discovered that his parents world was circular, enclosing home, fields, family, meetinghouse, the rural arches of Christian Annandale, the interwoven community of Presbyterian Scotland. For generations the pattern had seemed to be permanent, but as he became a young adult it was his misfortune to find that his consciousness was the center of a circle that was collapsing. At its center was the new Victorian consciousness, crying like an infant in the night.

He was born long and lean to thickset parents. From the very beginning his fragility and his differentness made him a subject of concern. When he was two, however, the birth of a brother distracted parental attention, and in the years that followed he was able to explore Ecclefechan with other preschool children: the smoke and manure of a small market village; rural peace and isolation alternating with market-day

Growing up in the shadow of the local meetinghouse, the young boy was taught to repress physical instincts. His parents Burgher-Secession affiliation focused on the small, elite community that in his childhood built its own meetinghouse in Ecclefechan, found leadership in the Reverend John Johnstone, and became famous throughout Annandale for pious sincerity. Too young to attend worship, he followed the well-beaten path between his home and the meetinghouse both in his circular imagination and in the religious routines of his family. Hearing the frenzied barking of a neighbors dog locked indoors, he took the familiar path to the open meetinghouse door and called out, Matty, come home to Snap. The subliminal voice of his parents community told him, among other things, that physical instincts came from the devil, not from God.

He sought two avenues of escape from the conflict that he began to feel between the restrictions of his parents community and his own and soon he discovered the ancient remains of the Roman occupation. In his excited imagination the Anglo-Saxon tower of Repentance Hill became a physical representation of that heroic period that had witnessed the creation of the tribal designations of the nation. As a young man, he read Wordsworth, Southey, and the other Lake poets. When he raised his eyes, the sunlit view across the Solway Firth to the Cumberland Hills and the Lake Country took on an additional soft resonance.

Birthplace of Thomas Carlyle, Ecclefechan. Photograph by J. Patrick. By permission of the Edinburgh University Library.

The same glow that illuminated the natural landscape connected it with the world of the only human community he knew in his childhood years. Strategically located and large enough to maintain a number of rural industries, Ecclefechan provided the surrounding farmers with a busy market. The young boy explored its commercial life, curious about people and their activities, apparently a familiar observer, particularly on weekly market days and at the frequent cattle fairs. Ecclefechan drew cattlemen, traders, merchants, and entertainers from all over southern Scotland, as well as the Italian with his mirrors and

James Carlyle was shaped by neglect. Food had been a luxury and self-help a necessity in his small but noncohesive family. As an adult, he reacted against this boyhood isolation, working with his second wife, Thomas mother, to make his own family into an intensely tight, self-sustaining unit. Whereas his father had been self-indulgent, lax, and undisciplined, James Carlyle became willful, purposeful, and defiant, the strongest-minded man his son ever knew. Whereas his grandfather cared little for religion, his father became a model of religious commitment.

It is doubtful that any single incident motivated James Carlyles turn to religion. Instead, he felt a gradually increasing sense of the sinful nature of all men and the uselessness of all activities that interfered with the acceptance of oneself as a sinner who could be saved by Gods grace. James Carlyle had ample evidence that he was a sinner, for he had inherited, among other qualities, the Carlyle family temper. As young men he and his brothers were notorious for their brawls, among the best drinkers and best headsplitters at the annual fairs of the village. Pithy, bitter-speaking bodies, and awfu fighters.

Silhouettes of James and Margaret Carlyle. Reprinted from Thomas Carlyle, Reminiscences, edited by James Anthony Froude (London, 1881).

But there were countervailing models to the anarchic, uncontrollable temper. The tradition of the Covenanters was strong in Annan-dale, the Secession Church had been formedthere was the Bible to read. Becoming grimly religious, he attempted to live every moment of his life as if salvation, the most important aim of mans existence, were to be approached only through a complete fulfillment of the rules and spirit of the Burgher Seceder Church.

Each day James Carlyle read the Bible to himself and his family. Calvin he knew indirectly through the Confession of Faith and the catechisms, Knox through the covenant and through echoes of The Book

The third but more shadowy avenue of escape for the bright young boy led into the schoolroom. His first schoolrooms were extensions of his parents world, combining both scholarly and religious values under the tutelage of young divinity students. No subject, not even mathematics, was unrelated to the religious view of the universe. But to the young student that connection did not have nearly the force of the actual body of knowledge that he had to master through study and memory. An alert student, capable at everything, he was motivated by approval to excel in those subjects, such as mathematics and Meetinghouse and schoolroom were interwoven.

The possibility that meetinghouse and schoolroom might not always be reconcilable, however, awakened his mothers anxieties. She trained his heart to the love of all truth and virtue. To this good being, intellect, or even activity, except when directed to the purely useful, was no all-important matter; for her soul was full of loftiest religion, and truly regarded the glories of this earth as light chaff. So Carlyle characterized the mother of Wotton Reinfred, his unfinished portrait of the artist as a young man. Training Toms heart in the values of the meetinghouse was his mothers highest priority. Intellect and activity were only of value insofar as they were practical necessities, and overwork was a threat to the health. Margaret Carlyle judged religious and moral habitudes of far more consequence than learning.