Contents

Thomas Carlyle

SELECTED WRITINGS

Edited and with an Introduction and Notes by

ALAN SHELSTON

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection first published in the Penguin English Library 1971

Published in Penguin Classics 1980

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 2015

Introduction and Notes copyright Alan Shelston, 1971

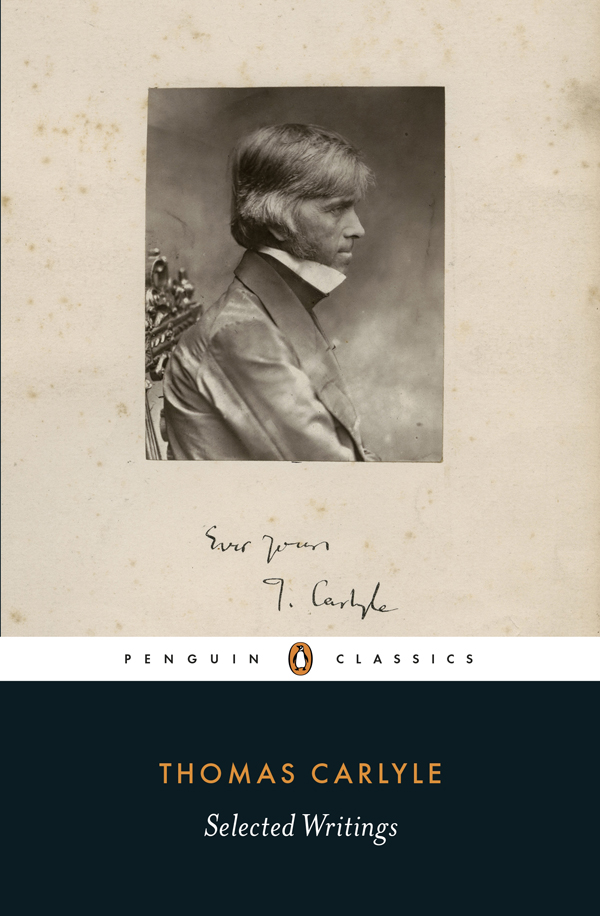

Cover photograph: Thomas Carlyle by Robert Scott Tait, 1854 National Portrait Gallery, London

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-241-20549-5

PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

THOMAS CARLYLE: SELECTED WRITINGS

THOMAS CARLYLE was born in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, in 1795. Intended by his family to become a Presbyterian minister, he was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment while at the University of Edinburgh and became a teacher instead. He later turned to literary work, publishing a life of Schiller and translations of Goethe in the 1820s. He married Jane Welsh in 1826; for a while they were forced to live in her remote farm to save money, but he began to publish his long series of major works with Signs of the Times in 1829 and Sartor Resartus in 18334. By the time his first truly successful book, The French Revolution, was published in 1837 (completely rewritten after John Stuart Mill had accidentally burnt the only copy of the manuscript), the Carlyles lived in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, and he became known as the Sage of Chelsea. Later important works included Chartism (1839), On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (1841) and Past and Present (1843). Carlyle was greatly admired by Ruskin and William Morris at this time, but his increasingly authoritarian and anti-democratic views also attracted a good deal of criticism. He published an edition of Cromwells letters and speeches, and biographies of his friend William Sterling and Frederick the Great. In 1866 he was heartbroken by his wifes death and, in his guilt that he had been a far from perfect husband, got his friend J. A. Froude to publish a very frank account of their life together which broke all the conventions of Victorian biography. He died in 1881.

ALAN SHELSTON was Senior Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Manchester until retirement in 2002. He has edited a number of Gaskells works including The Life of Charlotte Bront (1975) and North and South (2005), and was joint editor with John Chapple of The Further Letters of Mrs Gaskell. He has published a selection of Hardys poetry and written on a number of nineteenth-century authors including Dickens and Henry James.

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

For my Mother and Father

Introduction

In his biography of Carlyle, published only a year after the death of its hero, J. A. Froude reprinted a letter written to Carlyle by an unknown fellow-countryman in 1870. After making the usual apologies for intruding upon greatness, the writer goes on to justify himself:

You know that in this country, when people are perplexed or in doubt, they go to their minister for counsel; you are my minister, my honoured and trusted teacher, and to you I, having for more than a year back ceased to believe as my fathers believed in matters of religion, and being now an enquirer in that field, come for light on the subject of prayer.

(Thomas Carlyle: A History of the First Forty Years of His Life, London, 1882, Vol. II, Ch. 1.)

The writer was one of the millions of Carlyles readers who, according to Froude, have looked and look to him not for amusement but for moral guidance, and his letter confirms Froudes emphasis on this aspect of Carlyles reputation when he wrote that

Amidst the controversies, the arguments, the doubts, the crowding uncertainties of forty years ago, Carlyles voice was to the young generation of Englishmen like the sound of ten thousand trumpets in their ears.

(Thomas Carlyle: A History of His Life in London, London, 1884, Vol. I, Ch. 11.)

For his own generation Carlyle was not simply a contributor to the Victorian social and intellectual debate, and not simply a particularly dramatic historian, he was a prophetic voice crying out with clarity and conviction amidst the apparent confusion of an age of change. John Stuart Mill, for example, while he became increasingly disenchanted with that Carlylean voice, nevertheless paid tribute to its force in words that emphasize its visionary quality:

I felt that he was a poet, and that I was not; and that as such, he not only saw many things long before me, which I could only when they were pointed out to me, hobble after and prove, but that it was highly probable he could see many things which were not visible to me even after they were pointed out.

(Autobiography, London, 1873, Ch. 5.)

There is a subconscious irony in the last part of that judgement, and Mill is very careful to distinguish between the kind of Carlyles appeal, and its actual content, but it comes with particular force from the inheritor of utilitarianism, the creed that Carlyle most detested. Almost all of Carlyles contemporaries seem to have acknowledged his significance: Alton Locke, the hero of Kingsleys novel, pays tribute to the general effect which his works had on me the same as they have had, thank God, on thousands of my class and of every other; Dickens described him as a man who knows everything, while George Meredith, with rather more discrimination, referred to him as the greatest of the Britons of his time Titanic not Olympian: a heaver of rocks, not a shaper. The more fastidious of the Victorians tended to hedge their bets thus Hopkins called him morally an imposter, and a false prophet, before conceding that I find it difficult to think there is imposture in his genius itself, while Matthew Arnold went so far as to describe him as a moral desperado but they were never able to ignore the message that was uttered with increasing urgency from his Chelsea retreat.

Initially Carlyles reputation survived his death in 1881: in 1900 alone nine separate editions of Sartor Resartus were published, and when cheap reprints of the classics became popular at the beginning of this century his works figured prominently amongst them. Much of his appeal, like that of Ruskin, was to the self-educated: there is an interesting testimony to this effect from Yeats, who in his

CLASSICS

CLASSICS