To my mother, Rose; my sisters, Ann and Theresa; my father, Vernon; my aunts, Nicey and Mary; Mr. Sam; my grandmother, Mom; my cousins, Joe, Bobby, Jimmy, and Margie; my heart, Marita; my children, Sandy, Rodney, Danielle, and Maya; my grandchildren, Harvey (Champ), Carlia, Darian, and Monroe; and my relatives, the Allens, the Halls, and the Chapmans

Earl Monroe

To Margaret Porter Troupe

Quincy Troupe

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

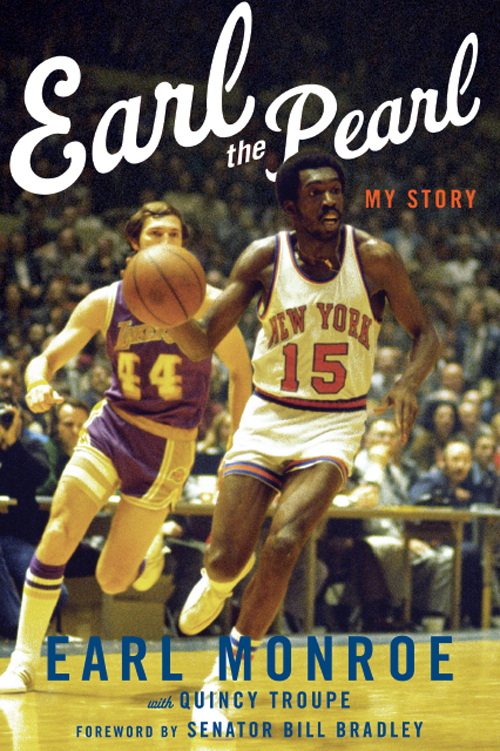

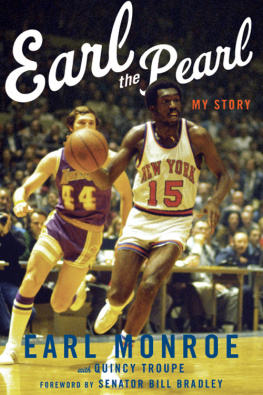

THERE HAS NEVER BEEN a basketball player like Earl Monroe. He wasnt the quickest guy in the league or overpowering physically, standing six foot three with a minimum of musculature on his frame, yet he was a uniquely great player. What set him apart was his control of the ball, his sense of the court, and his uncanny ability to gauge the distance between himself and anyone who could block his shot. When he had the ball, each part of his body seemed to move independently, controlled by a single command center. Among his manifold skills, his spin move became unstoppable. He drove toward the defensive man only to turn his back on him at the last possible second before collision, pivot with his left foot, and head away at a forty-five-degree angle. What was different from any other players spin was Earls one-handed control; it was as if the ball were attached by a short string to his fingers. When he was in a playful mood, he spun, let the ball hang suspended in air, crossed his hands like an umpire calling a runner safe, looked one way and touch-passed it in the opposite direction. At such moments, a murmur would ripple through the crowd and burst into an explosion of shouting, clapping, laughing, and stamping of feet. It was thus that Earl became The Pearl, and, more appropriately, Black Magic, because he made things happen with the ball that defied explanation.

Someone once asked Earl how he decided what to do on the court. He replied that he didnt know what he was going to do until hed done it. Like a great jazz artist, he created in the moment.

When Earl was traded from Baltimore to New York in the early seventies, people said that the Knicks would need two basketballs to satisfy the scoring ambitions of its new backcourt duo, Earl Monroe and Walt Frazier. It didnt turn out that way. What people didnt know was the strength of Earls dedication to winning. In New York Earl changed his game. In a sense, he sacrificed superstardom for his team. He learned to play within a much more structured offense and demanding team defense. He never complained; he made himself fit in. Still, there were nights when the magic could not be contained.

I remember a game against Milwaukee in the 19721973 season. The Knicks were behind by 19 points with about 6 minutes to go. The fans were already starting to leave Madison Square Garden. Then suddenly Earl took over the game and scored repeatedly. At one point in those closing minutes, he jumped, changed the position of the ball three times, and floated it over the outstretched hand of Milwaukees center, seven-foot-two Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. On his next two forays he drove directly at his man, then spun left, took two more dribbles, and made each shot from the baseline. The same thing happened in the final game of the 1973 NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. When our stalwart forward, Dave DeBusschere, went down with a badly sprained ankle, Earl would not let us lose. We took energy from his play and elevated our game that night down the stretch, winning our second NBA title in four years and giving Earl what every player, deep down, yearns fora championship.

For all of Earls athletic achievements, what sets him apart is his character: He grew up in a tough Philadelphia neighborhood, but without becoming a tough himself; he encountered persistent racism, but he never turned bitter; he was well aware that he had special basketball skills, but he never gave in to arrogance. There is a remarkable peace at the core of his personality. The flamboyance of The Pearl exists right alongside the gentleness of off-court Earl. People are always glad to see him. He never complains. He smiles easily. Even as he went through five hip operations, five back operations, eleven sinus operations, and countless stomach problems from all the ibuprofen he took in his playing days, he exuded his own brand of joie de vivre. His quiet strength made him unselfish as a player and continues to make him cherished as a friend. In my twenty years in politics, I asked Earl to come to many of my political events and share the memory of his magic with my supporters. He never once refused.

At the end of the day, Earl seems to know that kindness is more important than on-court heroics and that those who love him count for more than those who applauded him. He accepts lifes ups and downs; neither overwhelm him. Balance on the court and balance in lifethis seems to be his motto. In Earl the Pearl, you will read his story in his own voice. The quiet man has finally spoken. It is a story worth reading, as his life has been a life worth leading.

Bill Bradley

New York City

PROLOGUE

WHEN I WAS 17 YEARS OLD, during the summer of 1962, after my senior year at John Bartram High School, there was a certain guy a couple of years older than me that I played against in a one-on-one game for the title of best young basketball player in all of South Philadelphia.

During my junior year in 1961, Matt Jackson, a senior at Bok Technical High School, was considered hands down the top basketball player in the city. That year he was the top high school scorer in all of Philadelphia, and after graduating he left the city to go play at South Carolina State College. Matt was a forward with a great bodyabout six feet five, six feet six inches tall and 220 poundsa close-cropped, quo vadis haircut, and a light brown complexion. He was what some would call a classic basketball player, you know, because he would back you down, shoot a turnaround jump shot over his opponent, or a little right-handed or left-handed hook shot in the lane or on either side of the basket. Though he wasnt fast or quick, he was a deadly shooter when he got his shot off, and he looked like a pro when he played the game.

On the other hand, I was six three and skinny, had long arms, and weighed around 170 pounds. My game was honed in the schoolyard, playground style, you know. I had slick moves and a crossover dribble in my bag of tricks, plus a pretty good jump shot from anywhere on the floor from 20 feet in and a lightning-quick spin move that got me anywhere on the floor and to the rim for layups or for tricky spin shots high off the backboard. But I had a game in the paint, close to the basket, too, because I played center, with my back to the basket, in high school. I had learned and honed my craft on playgrounds with the best opponents Philadelphia had to offer, and I felt I was ready to play anyone from anywhere, any place, anytime. In other words, my confidence level was very high at this time.

But my confidence hadnt always been this great. In fact it was during the summer before this showdown, in 1961, that I began to put the building blocks into place that would help me elevate my game to another plateau. At first, when I was growing up, I was a baseball and soccer player. Basketball didnt become my great love until I was 14 years old, when I was attending Audenried Junior High School. I was already six three by then, and I started playing with a group of guys from Audenried that included Steve Smitty Smith, George Clisby, Leaping John Anderson, Ronald Reese, and Edwin Wilkie Wilkinson. Later, on the 30th and Oakford Street playground, we formed a team called the Trotters. Not that we played like the Globetrotters, because we actually fashioned our team game style after the Boston Celtics.

![Monroe - The summers end. [Bk. 3]](/uploads/posts/book/221395/thumbs/monroe-the-summer-s-end-bk-3.jpg)