Table of Contents

To Lydia Julianne Radike My war bride and lifelong companion

Praisefor ACROSS THE DARK ISLANDS

Highly recommended to anyone interested in the role of infantry in the Pacific Theater of WWII.

JOHN H. FOUSH, JR., D.B.A., Colonel AUS-Ret.

Radike can describe a battle with singular detachment and a few carefully chosen words that convey danger, death, and heroism without a hint of hyperbole.

Proceedings

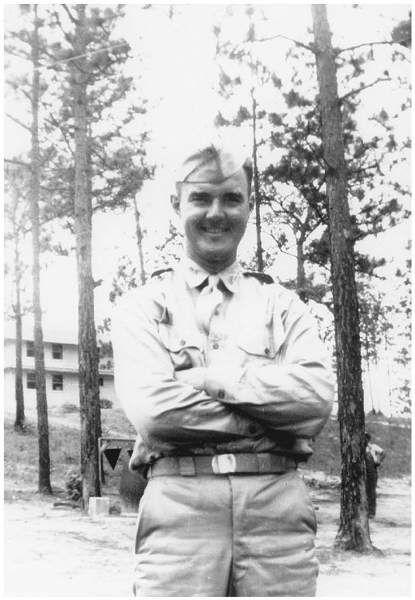

Floyd Radike, Fort Benning, Georgia, after the ceremony commissioning him as an officer on July 23, 1942.

INTRODUCTION

The Fork in the Road

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more.

We stood at the rail looking out in the darkness of Nandi Bay. There was no moon, but the light that flows back from the sky even on the darkest nights showed the ships of the convoy, like great sleeping cats resting on the smooth, unruffled waters.

Off to the east we could see the occasional flicker of light from the native huts on the shore. Every ship in the bay is blacked out, Obie said. Youd think the natives would be told to keep their lights under cover.

I had been thinking about something else, and only picked up some reference to natives in Obies remark.

What about natives? I asked. Obie pointed out into the darkness.

If theres an enemy submarine out there, he can tell there are ships in the bay by the way those lights are blacked out as he moves across the entrance.

That sounds a little far-fetched, I retorted. That destroyer screen we saw out there at sunset would keep them too far out for that kind of look-see. Besides, Im sure the Japanese know were here. They seem to know everything that goes in or out of Pearl.

And, I added as a clincher, those two calls to general quarters we had on the way here were for real, according to the navy guys we eat with.

We could hear the motor of an approaching navy launch. Looking over the side, we could see a blacked-out flashlight being swung back and forth as its owner looked for the gang-plank. He evidently found it because we heard a loud thud, the sound of voices from the launch, and the crisp bark from the deck officer to look sharp.

Several men debarked and ramped up the gangway, including the owner of the flashlight. We moved closer to see who was coming aboard. It was too dark to see the faces clearly, but one arrival had the cotton uniform of an army officer, while the other, surprisingly, was wearing shorts, knee-socks, and a large cap.

British, Obie whispered.

Or colonial, I replied.

What? Obie questioned.

ColonialAussie or New Zealander, I answered. We moved back to our former position. There was a lot of activity on the ship. Men passed us and clattered down the iron ladders. Others clattered up the ladders and moved in the opposite direction. Strangely, these travelers were silent. Usually you could pick up a conversation as they moved along slowly in the dark. By the time they had passed out of ear-shot, you knew what the topic of their conversation was.

Something must be up, Obie said.

You mean, because nobodys talkin?

Thats right, Obie continued. I havent heard so much silence since that sub scare off the Horn Islands.

We each settled back into our thoughts. I began reviewing the events of the past week.

The departure from Pearl had been an event. It took place on the first anniversary of the sneak attack. There were ceremonies all over the place, bands playing, Taps being sounded on a half-sunk battleship, and overflights of navy fighters. But our interest was elsewhere, the harbor being full of troopships, cargo carriers, tankers, and destroyers.

Before noon, we had upped anchor and joined the long line going through the submarine nets at the harbor entrance.

Several hours out we picked up some big stuff, a cruiser, a carrier, and a battleship. We were positioned midway in the convoy, and this gave us a seat on the fifty-yard line: in every direction we saw the evidence of resurgent military and naval power. It was comforting to see this much hardware, after the horror stories wed heard on Oahu of the poor shape we were supposed to be in.

The next several days were uneventful. Our quarters below-decks were the navy version of the Black Hole of Calcutta: the bunks were stacked five high, the top bunk had eighteen inches of vertical spaceand you knew that every guy you saw with a bruise on his forehead slept in a top bunk.

The bottom bunk was six inches off the deck, which ensured your being stepped on or kicked by someone blundering along in the light from a single bulb. It was hot, humid, and without any possibility of fresh air, and it stank of all the unwashed, perspiring, and seasick inmates of this bedlam.

Despite all the nagging shortcomings of heat, crummy chow, crowding, and smell, the men soon settled into a routine. The American soldier is the most adaptable of men. Within a few hours, no matter how crude the environment, he will have mastered his surroundings and be prepared to go on for days with his pattern of accommodation.

The day was divided into three partsbreakfast, lunch, and dinner. Each meal called for an hour in the steam room the navy facetiously called a mess. After each meal some time was passed on deck reveling in the fresh air and sunshine, then it was below-decks for sack time until the next Now hear this... announced the next punishing ritual in the steam room.

Such activities, desperate and meaningless as they were, could lead to a parallel condition of thought known as coming apart at the seams. But this was forestalled by the glue, the adhesive if you will, that bound everyone together, gave them social cohesion and purposethe rumor.

We didnt know where we were going, the vast majority of us, that is. And that meant that positive information had to be supplanted by pulling together chance remarks, the appearance of strangers, the slowdown in mail, and the propaganda blandishments of Tokyo Rose.

It is hard for anyone outside the service to understand the power and pervasiveness of the rumor. Office gossip, back-fence conversation, the ritual coffee clique, the informal channel of communicationnone of these civilian counterparts, no matter how frequently used, or how freighted with purported significance, can hold a taper to the military rumor.

It is the nature of service life that you never know what will happen next. The ostensible purpose of keeping the troops in the dark is to prevent the enemy from finding out what is in the works. But nature abhors a vacuum, we are told, and in the void created by his masters the soldier creates his own scenario. No intelligence service is more rigorous in examining every happening for a clue to the future, because a good rumor must always begin with, A guy over at who works for G said. The blanks can be filled in with any reasonable place or name that seems to enhance the validity of the rumor.

For one to be called in to see a field-grade officer, to be engaged in an eyeball-to-eyeball conversation with a ships first mate, to meet a bustling lieutenant coming out of the communications shackany of these will prompt our friends to inquire, Whats the latest rumor?

Next page