Table of Contents

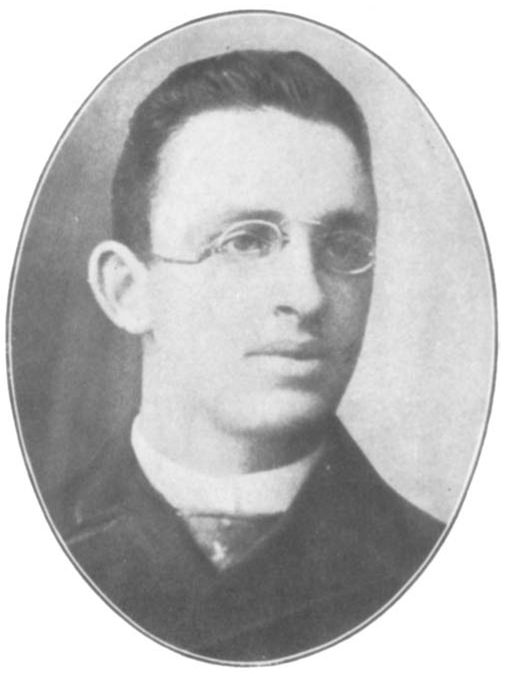

ALEXANDER BERKMAN At the time of the Homestead Strike

As for my fame (God help us!) and your infame, I would be willing to exchange a good deal of mine for a bit of yours. It is not hard to write what one feels as truth. It is damned hard to live it.

Eugene ONeill to Alexander Berkman

January 29, 1927

Foreword

We owe thanks to Gene Fellner for gathering in one volume the writings of that extraordinary American, Alexander Berkman. Yes, American, though Berkman might rebel at this description as he rebelled at almost everything, but though he was born in Russia and deported from this country in the wave of anti-radical deportations following World War I, his chief political activity was in the United States over a period of twenty-five years.

Our gratitude to Gene Fellner is in good part due to the fact that Alexander Berkman is one of those lost heroes of American radicalism, a rare pure voice of rebellion against the state, against capitalism, against war. To bring Berkman to public attention is to present to all of us, and especially to a new generation of young people looking for guidance in a chaotic world, an inspiring example of living an honest life, as well as a vision of a better society.

I doubt you will find the name of Alexander Berkman in any history textbooks used in American schools and colleges. In my many years of studying history, through college and graduate school, up through earning my doctorate at Columbia University in history and political science, I never read or heard the name of Alexander Berkman.

Nor, for that matter, did I hear the name of his life-long comrade, Emma Goldman. True, she is much better known today, since the womens movement of the Sixties resurrected her and brought her into the popular culture, to the point where she became a character in a Hollywood film (Warren Beattys Reds) and in a well-known novel (E.L. Doctorows Ragtime).

No such attention has been given to Alexander Berkman, though he and Emma Goldman were close associates through a number of remarkable events in American historythe attempted assassination of the industrialist Henry Clay Frick in 1892, the protests against American entrance into the first World War.

I did not get interested in Emma Goldmanthough I vaguely knew of her, until around 1970, when I met a fellow historian, Richard Drinnon, who told me about his biography of Emma Goldman, titled Rebel in Paradise. It was there, and in Emmas extraordinary autobiography, Living My Life, that I learned how important Alexander Berkman was to her, and how their lives intertwined over the years.

Berkmans Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist is surely one of the great works of prison literature, but it was long lost, out of print, and Gene Fellner here reproduces some of its most poignant and powerful moments.

When I began teaching political theory at Boston University in the 1960s, I became aware that the ideas of anarchism were missing from the orthodox histories of political philosophy. I knew that Berkman had written about anarchism, but I could not find any of his writings. However, I discovered that a small anarchist press in England had published a 100-page pamphlet by him, called The ABC of Anarchism.

After reading it, and deciding that it was the most concise and lucid presentation of anarchist philosophy I had come across, I ordered hundreds of copies to be shipped from England for my students to use. Gene Fellner, in this volume, gives us a substantial portion of that pamphlet. Reading it will be an eye-opener for anyone not sure of what anarchism is.

The most common error about anarchism is that it espouses violence. Berkmans discussion of violence, in The ABC of Anarchism is remarkable for its subtlety and sophistication. It is as persuasive as any argument I have seen on the subject.

Berkman and Goldman were disillusioned with the Soviet Union and its distortion of the communist idea long before that became clear to so many others on the Left. His writings about that, reproduced here, came from experiencing the early years of Lenins rule at first hand. What he had to say will be especially interesting today, after the collapse of the Soviet experiment.

In Europe one year, looking for material that would be useful in a play I was writing about Goldman and Berkman, I spent some time in the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. There I found the fascinating correspondence between Emma and Alexander, once lovers, always close friends, written during the years of their European exile, after deportation from the United States. I was happy to see a number of those letters reproduced in Gene Fellners volume.

Altogether, this anthology is a wonderful introduction to a much overlooked but extraordinary figure of recent history. It is also a welcome introduction to the ideas of anarchism, which appear more and more relevant in this era of bullying governments, corporate ruthlessness, and endless war.

Howard Zinn

Auburndale, July 2004

Introduction

My attitude, wrote Alexander Berkman to Emma Goldman in November 1928, always was and still is that anyone preaching an idea, particularly a high ideal, must try to live, so far at least as possible, in consonance with it. Berkman did exactly that from the time he was punished in school, at the age of 13 in 1883, for having written an essay entitled There Is No God to his death, by suicide, in June 1936. He was a remarkable figure, determined, committed, and fearless; a brilliant organizer and a compelling writer. He suffered prison, torture, sickness, deportation and statelessness because of his political beliefs, but nothing was able to break his spirit or diminish his commitment to anarchism. Through it all he remained convinced that freedom of thought must never be subject to laws nor individuals subject to governments.

In 1892 Berkman was sentenced to 22 years for his bungled attempt on the life of Henry Frick, the labor magnate, during the Homestead Strike. He was convinced he was striking a blow for labor but failed to kill Frick, though he shot him at close range. When he was released, after 14 years, he wrote a compassionate and insightful book, Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist (1912), which documented his life behind bars and included not only accounts of torture and solitary confinement but also of sexual feelings within prison, including his growing love for a fellow inmate, and of the loneliness and desperation of prison life. During these years of confinement, Berkman remained active, publishing a clandestine prison newspaper, attempting a desperate escape, working to improve prison conditions, and coming to grips with the fact that not even the workers understood, much less supported, his attempt on Fricks life.

On his release from prison Berkman immersed himself in political activity, touring the country to lecture against restrictions on freedom and organizing among the unemployed. He edited Emma Goldmans Mother Earth and his own magazine, The Blast, despite constant harassment by the authorities. He coordinated demonstrations against the massacre of miners in Rockefellers mines in Ludlow, Colorado in 1913 and when a bomb, possibly intended for Rockefeller, exploded in the New York City tenement apartment of four anarchists, Berkman organized a public funeral for them in Union Square that was attended by 20,000 demonstrators. During this period Berkman founded the Anti-Militarist League and helped found the Ferrer Free School in New York City. When war fever began sweeping the country and the government cried out for U.S. citizens to be prepared to fight, Berkman became one of the most effective organizers against conscription. He spoke before tens of thousands of people about anarchism and the lunacy of war at a time when many were receptive to his message, when the government felt threatened by it, and when to speak against U.S. entry into World War I was to put your life in danger. It was due largely to his tireless efforts that Thomas Mooney, falsely convicted of throwing a bomb into the July 22, 1916 preparedness parade in San Francisco, was not executed.