Table of Contents

SHOW TRIAL

FILM AND CULTURE SERIES

FILM AND CULTURE

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

For the list of titles in this series, see .

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54746-8

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-231-18778-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54746-8 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

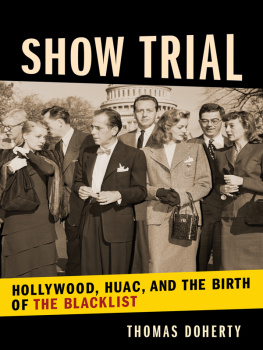

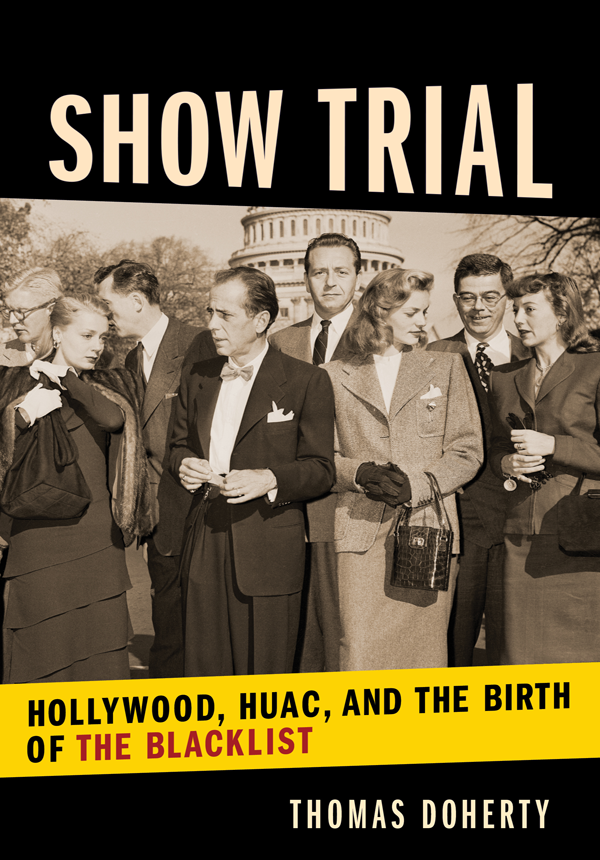

Cover image: (front) The Committee for the First Amendment arrives on Capitol Hill to protest the tactics of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, October 27, 1947. (Left to right) Richard Conte, Philip Dunne, June Havoc, John Huston, Humphrey Bogart, Paul Henreid, Lauren Bacall, Joe Sistrom, and Evelyn Keyes. Bettemann/Getty Images. (back) An anti-Communist pamphlet by friendly witness Oliver Carlson, published by the Catholic Information Society, 1947.

CONTENTS

I n 1947 the Cold War came to, or rather was declared on, Hollywood. The year would see a parade of stoic motion picture personalities trudging up Capitol Hill, testifying before hostile committees, and entering into the pages of the Congressional Record. When the power center that was Washington discovered the publicity magnet that was Hollywood, the resulting headlines could only cement the relationship.

Long anticipated and extravagantly hyped, the main event lived up to advance billing. Over nine days in October 1947, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), chaired by a dapper martinet named J. Parnell Thomas (R-NJ), held its soon-to-be notorious hearings into alleged Communist subversion in Hollywood. Officially dubbed Hearings Regarding the Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry, it was the first full-on media-political spectacle of the postwar era. Like the kickoff for a successful franchise, it spawned like-minded sequels, but the first episode attracted the widest publicity and left the harshest legacy. Subsequent versions were low-energy imitations; the original was the high-intensity template.

The compulsion to render the politics as performance was understandable: the hearings boasted all the trappings of a gala Hollywood premiereglamourous stars, colorful moguls, emotional outbursts, and wide-eyed looky-loos, all recorded under the hot lights of the newsreel cameras and broadcast over radio. The capitals biggest show of the year opens this morning when the House Committee on Un-American Activities, probing Communist influences in Hollywood, calls the first of 50 gilt-edge names as witnesses, ran the front-page notice in the Hollywood Reporter. Despite the stage being Washingtons largest hearing room, space for the public will be SRO, and then only for the first few able to squeeze in.

In all, forty-one witnesses were calledstudio executives, official representatives of the motion picture industry, producers, directors, screenwriters, actors, critics, investigators, and lawyers. The first week was given over to witnesses mainly sympathetic to the committee, or at least not openly hostile, and were called friendly witnesses, collectively Friendlies. The recalcitrantsnineteen in allwere dubbed unfriendly and embraced the tag as a badge of honor. The Unfriendly Nineteen were whittled down during the hearings to the Unfriendly Ten, or the Hollywood Ten, although at the time Hollywood wanted no part of them.

The declaration marked the formal onset of the blacklist era, a two-decade long purgatory during which political allegiances, real or suspected, determined employment opportunities in the entertainment industry. At the studios and the networks, hundreds of artists were shown the dooror had it shut in their faces.

But if the investigation destroyed careers, it also made them: three of the friendly witnesses ascended to pinnacles of power in the city they had come to under subpoena: the actors Robert Montgomery, who went on to serve as chief media advisor to president Dwight D. Eisenhower; George Murphy, who served as senator from California (19661971); and Ronald Reagan, who served two terms as governor of California (19671975) and president of the United States (19811989). Among the professionals on the dais, ironically, only one made serious political capital out of his HUAC service: Richard M. Nixon, then a freshman congressman from California, who leapfrogged from the House of Representatives to the U.S. Senate (19501953) and thence to the vice presidency (19531961) and presidency (19691975). Though not as upwardly mobile as Nixon, one of the ex-FBI men working for the committee, investigator and occasional interrogator H. A. Smith, also used his congressional sheen to move into a bigger chair, in Congress in fact, as a representative from California (19571972).

Convinced that Hollywood was a breeding ground for a pestilent ideology, HUAC set aside labor unions, government agencies, and the U.S. military to allocate enormous investigatory resources to a site devoted to the construction of dream castles. Were the congressmen cynical pols dragging Hollywood through the mud to grab headlines or noble sentinels flushing out a clear and present danger? Even W. R. Billy Wilkerson, the fervently anti-Communist editor-publisher of the Hollywood Reporter, suspected motives that were less than civic minded. How better can the committee grab front page space, how easier can the personnel of that committee get their names in print, than by an attempted shakedown of motion pictures and their personalities? he asked, knowing the answer.

Rivaling the metaphors of showbiz razzamatazz, a more haunting parallel, dredged up from the dark recesses of American history, made the rounds: the witch hunt. To the men brought before the tribunal, the hearings were courts of Oyer and Terminer convened to condemn them as malefactors. Having prejudged the case, the presiding magistrates were not seeking justice but staging a show trail to accuse, indict, and punish. In truth, in the next decade, the HUAC hearings evolved into a quasi-religious ritual of confession, contrition, and self-flagellation in which the accused were to acknowledge their sins, seek forgiveness, and perform penance. In 1947, however, the cried-out-upon were proud heretics willing to go to the stake rather than deny the true faith. For the judges and the accused alike, the Hollywood hearings were truly a showa stage-managed production with a script already written.

Of course, no one was actually burnt, or hanged, or pressed to death with stones for practicing the black arts of Soviet subversion. No matter how hysterical the rhetoric on both sides, what happened in America in 1947 was not the Salem Witch Trials, still less a Stalinist purge or Nazi blood bath. All the accused retained legal representation, exercised freedom of speech, and received due process in the courts. The Unfriendlies may not have been allowed to read their defiant statements before the committee, but they were hardly muzzled: the group handed out copies of their statements, published ads in newspapers, exhorted supporters at rallies, and produced fund-raising films. Most were wordsmiths by trade and incapable of shutting up.