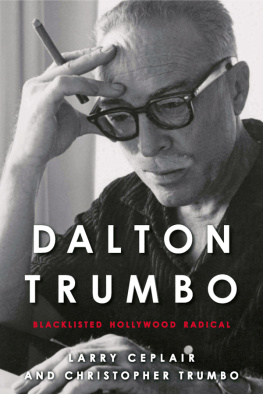

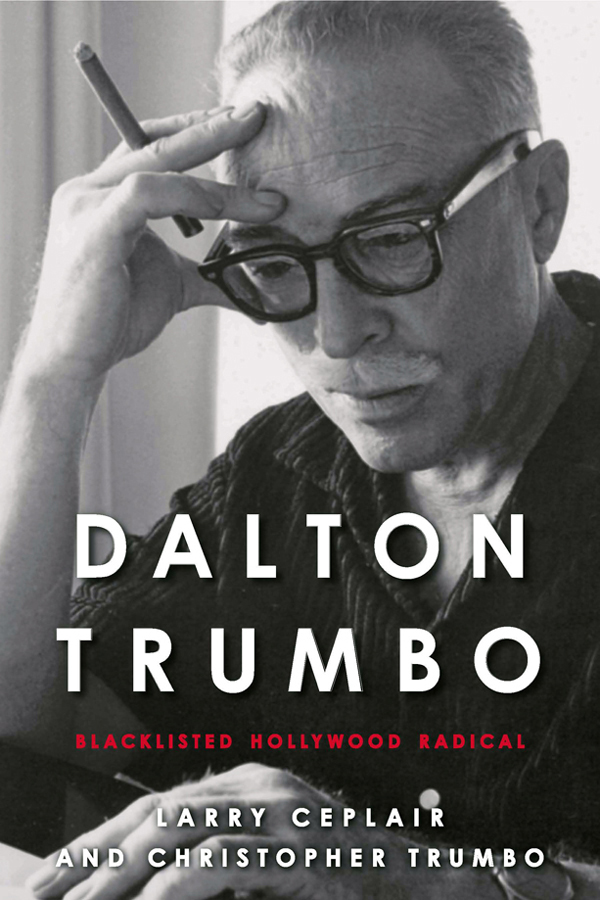

DALTON TRUMBO

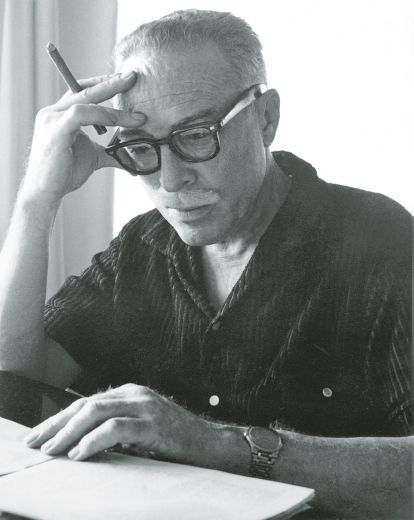

Dalton Trumbo, 1959. Photograph by Cleo Trumbo.

DALTON TRUMBO

Blacklisted Hollywood Radical

Larry Ceplair

and

Christopher Trumbo

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2015 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Frontispiece: Dalton Trumbo, 1959. Photograph by Cleo Trumbo.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4680-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4681-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4682-9 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

To Mitzi Trumbo and Nancy Escher, for their unstinting support; and to Christine Holmgren, for her unwavering love.

Introduction

For the only thing

That makes sense in life

Is Struggle!

Dalton Trumbo

This was supposed to be Christopher Trumbos book. He (and his two sisters, Nikola and Mitzi) knew Dalton Trumbo best. They experienced the blacklist periodtheir fathers inquisition by the Committee on Un-American Activities, his imprisonment, the familys sojourn in Mexico, and fourteen years of aliases and fronts. Christopher had studied and thought about the subject for many years and had amassed a prodigious amount of research data, but the fates did not allow him the time he needed to complete the project. In December 2010, knowing he did not have much longer to live, he asked me to finish the book for him. He died a few weeks later, on January 8, 2011.1 Thus, this has become my book, and he has become a reader over my shoulder.2

Christopher had been the subject of many interviews; in addition, he had recorded many of his ideas and thoughts, made copious notes, and composed a series of extended commentaries. He is quoted extensively throughout this book, and for the sake of clarity, his words are presented as quotations. What follows is an approximation of what he might have written by way of an introduction:

For a long time, I stayed on the sidelines of the history of the blacklist. But in 1995 I decided I had better start taking charge of this, mostly because there was a lot that I knew that other people didnt, and I knew that my experience of the blacklist period was unique. My ideas first took shape in the form of a play I wrote to help raise money for a First Amendmentblacklist sculpture.3 [That play, Trumbo: Red, White and Blacklisted, was first performed on November 24, 1997. Six years later it opened in New York City, directed by Peter Askin. Askin then adapted it for his documentary film titled Trumbo. Christopher worked closely with him on both projects.]4

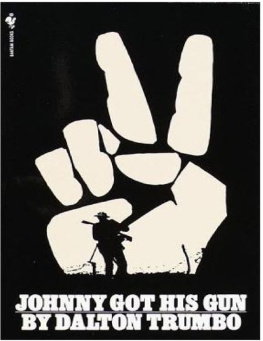

The play succeeded in telling a particular kind of story, or the story in a particular way and had a particular kind of effect. The documentary film, though it covered the same time period, had a very different effect. You can do things with a documentary film that you cant do with a play. The same is true of a book, and I think a book about my father will finish off a lot of what I think is worthwhile knowing about him.5 The book I have in mind will answer the questions people have about Trumbo, tell the story of his life, clear up the misconceptions, distortions, and lies that have accumulated over the years, and place him in proper context. It will straighten out the historical record, and it will include insights that can only be provided by somebody who knew him well. It will tell the story of a man who won a major book award [for Johnny Got His Gun], stood up to the House Committee on Un-American Activities, sacrificed a career for principle, gave to his foes as good as he got from them (and maybe then some), spent a year in prison for refusing to change his opinions, wrote the script [Roman Holiday] that would make Audrey Hepburn forever a princess in our minds, won two Academy Awards [Roman Holiday and The Brave One], and engineered the destruction of the Hollywood blacklist.

As he had done for the play, Christopher intended to use letters as the backbone of his book. The letters he used in the play were carefully selected to balance the defeats Trumbo suffered. That he was writing humorous and graceful letters at the same time as he was handling all that other stuff gave the audience a larger picture of what he was like. Dalton Trumbo loved letters, and he wrote thousands of them. They were, in effect, Trumbos journal, a means of keeping track of the important events and people in his life and the battles he fought. He kept copies of almost all those letters, and collectively, they provide the reader with an indelible image of Trumbos place in the world he lived in.

Letters were also, for Trumbo, a form of amusement, a way to acknowledge the absurdities he saw all around him. He said: If you can write an amusing letter, you know someone is going to laugh at it. And I like absurdity. And absurdity is rarely spontaneous. It takes constructing. Absurdity takes careful thought. My sense of the absurd is well developed.6 It is clear that everything Trumbo wrote was carefully thought out; his archive is filled with notes, drafts, and multiple rephrasings of his ideas. According to Mitzi, he never dashed off a letter, or even something as simple as a shopping list. Letters were for him an art form, a sort of haiku and performance. Indeed, from an early age, Trumbo consciously practiced language as performance.

The letters also provided him with a stage for his humor. He was, Christopher recalled, a very funny guy, and his was regularly the loudest voice in the room. People learned not to duel with him verbally, because he always put them away. His saving grace was that he was also very humorous about himself and his personal predicaments. (In an undated, handwritten note, Trumbo scribbled: God put me in a position to make a fool of myself, but no one expected me to take such glorious advantage of it.)7 Michael Wilson said at Trumbos memorial, One cannot understand the man unless one appreciates his mordant sense of humor.8

An understanding of Trumbo also requires an appreciation of the leitmotif of his adult life, which he identified in the cover letter that accompanied several dozen boxes of his papers he sent to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research in 1962:

Next page