For Ella

I am absolutely enchanted in all senses of the word by passion. It is what guides us through the unknown like an experienced commander; angry seas never scare us when we face them with the madness of love. Of all nations, none has a people that loves and falls in love more than mine. We are surrounded by exaggeration, happiness, spontaneity and creation. The expression of hope on our faces is the trademark even of those who have never received the tiniest advantages of society. We devotedly believe in the new world and in the beautiful humanity we know we will construct, without the muzzle that can take our freedoms away or the whips that try to frighten us. Without the ignorance that would lead us to the stupor of an empty cocoon.

Our populace that was born enslaved frees itself every day with a soaring voice in search of the truth. Its truth. That which bases its strength in an irremovable culture because it comes from the soul, from the aura, from the smile, and where whites and Indians, blacks and the poor, migrants and the young delight in lifes pleasures. And what pleasures! A people who know what they really want even though they dont recognise how. Or do they?

The answers that we search for require special care and attention.

We are a people of a thousand faces and gestures. A people fighting to preserve our history against everything and against all the evidence and possibilities. A shrewd, vain and happy people who make good use of our natural wonders with the naturalness of the carefree. A people who love everything around them and who know how to extract the wisdom of a lifetime from every second. And a people who love football.

Football is a sport made from spontaneity and discernment, luxury and freedom, and one that, I believe, is part of our most primitive genome, like dance. But football should also be a type of dance. A dose of peace.

Alex Bellos, with the characteristic patience of a sage and the charmed curiosity of a scientist, shows us, with irrefutable clarity, our face and our soul. Just like a life theatre in which we watch and discuss our daily lives without getting involved with its banality, our enchanted and enchanting neobrazilian travels across our immensity to discover who we are and why we are. And achieves this, with discernment and a rare sensibility.

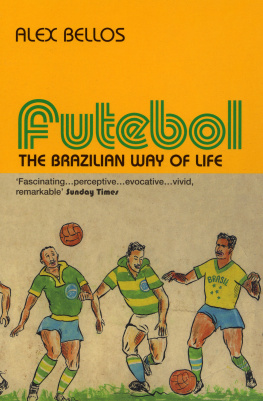

Futebol was originally published in 2002. Updates are included at the end of individual chapters, and a new postscript appears at the end of this edition.

London

January 2014

Football arrived in Brazil in 1894. The violent British sport did unexpectedly well. Within decades it was the strongest symbol of Brazilian identity. The national team, as we all know, has won more World Cups than anyone else. The country has also produced Pel, the greatest player of all time. More than that, Brazilians invented a flamboyant, thrilling and graceful style that has set an unattainable benchmark for the rest of the world. Britons call it the beautiful game. Brazilians call it futebol-arte, or art-football. Whichever term you choose, nothing in international sport has quite the same allure.

I arrived in Brazil in 1998. I didnt do badly, either. I became a foreign correspondent. It was a job Id always coveted and, journalistically speaking, Brazil is irresistible. The country is vast and colourful and diverse. Among its 170 million population there are more blacks than any other country except Nigeria, more Japanese than anywhere outside Japan, as well as 350,000 indigenous Indians, including maybe a dozen tribes who have not yet been contacted. Brazil is the worlds leading producer of orange juice, coffee and sugar. It is also an industrialised nation, curiously one of the worlds leading aeroplane-makers, and it has an impressive artistic heritage, especially in music and dance.

And, of course, theyve got an awful lot of football.

Soon after I arrived I went to see the national team play. It was at the Maracan, the spiritual home of Brazilian ergo world football. When the players filed on to the pitch, we jumped and cheered. The noise was like an electric storm, a rousing chorus of firecrackers, drumming and syncopated chants. It crystallised what I already knew; that the romance of Brazilian football is much more than the beautiful game. We love Brazil because of the spectacle. Because their fans are so exuberantly happy. Because we know their stars by their first names as if they are personal friends. Because the national team conveys a utopian racial harmony. Because of the iconic golden yellow on their shirts.

We love Brazil because they are Braziiiiiiiiiil.

As a sports fan, I immediately took an interest in the domestic leagues. I read the sports pages, adopted a club and regularly went to matches. Following football is perhaps the most efficient way to integrate into Brazilian society.

As a journalist, I became increasingly fascinated with how football influences the way of life. And if football reflects culture, which I think it does, then what is it about Brazil that makes its footballers and its fans so... well... Brazilian.

Thats what this book is about.

I first wanted to know how a British game brought over a little over a century ago could shape so strongly the destiny of a tropical nation. How could something as apparently benign as a team sport become the greatest unifying factor of the worlds fifth-largest country? What do Brazilians mean when they say, with jingoistic pride, that they live in the football country?

If football is the worlds most popular sport, and if Brazil is footballs most successful nation, then the consequences of such a reputation must be far-reaching and unique. No other country is branded by a single sport, I believe, to the extent that Brazil is by football.

The research took me a year. I flew, within the countrys borders, the equivalent of the circumference of the world. I interviewed hundreds of people. First, the usual suspects: current and former players, club bosses, referees, scouts, journalists, historians and fans. Then, when I really wanted to get under the countrys skin: priests, politicians, transvestites, musicians, judges, anthropologists, indian tribes and beauty queens. I also interviewed a man who makes a living performing keepie-uppies with ball bearings, rodeo stars who play football with bulls, a fan who is so peculiar-looking that he sells advertising space on his shirt; and I discovered a secret plot involving Scrates and Libyas Colonel Muammar al-Gadaffi.

I was not interested in facts, like results or team lineups. Brazil is not big on facts anyway; it is a country built on stories, myths and Chinese whispers. The written word is not yet as trusted as the spoken one. (One of the countrys more infuriating customs, especially if you are a journalist.) I was interested in peoples lives and the tales they told.

The result, I hope, is a contemporary portrait of Latin Americas largest country seen through its passion for football.

Brazil is the country where funeral directors offer coffins with club crests, where offshore oil rigs are equipped with five-a-side pitches and where a football club can get you elected to parliament.

I started my research in mid-2000, exactly half a century after the World Cup was held in Brazil and thirty years after Brazil won, so spectacularly, the title for the third time. It was a convenient starting point for reflection on the legacy of futebol-arte.

Next page