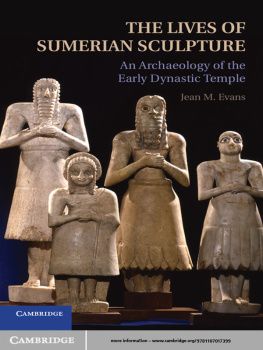

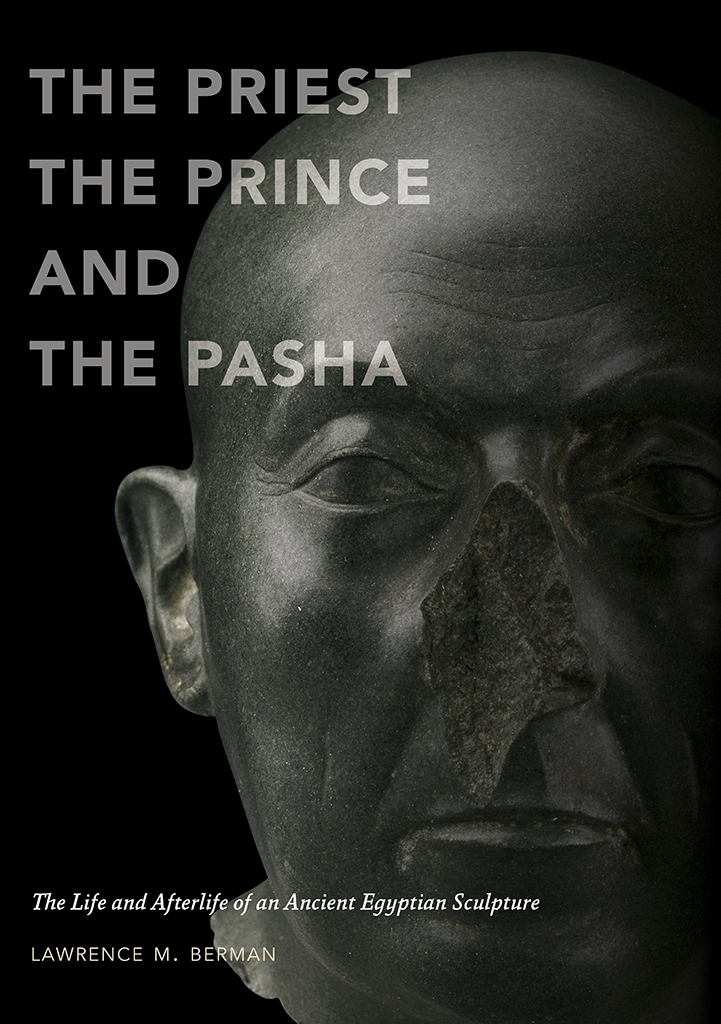

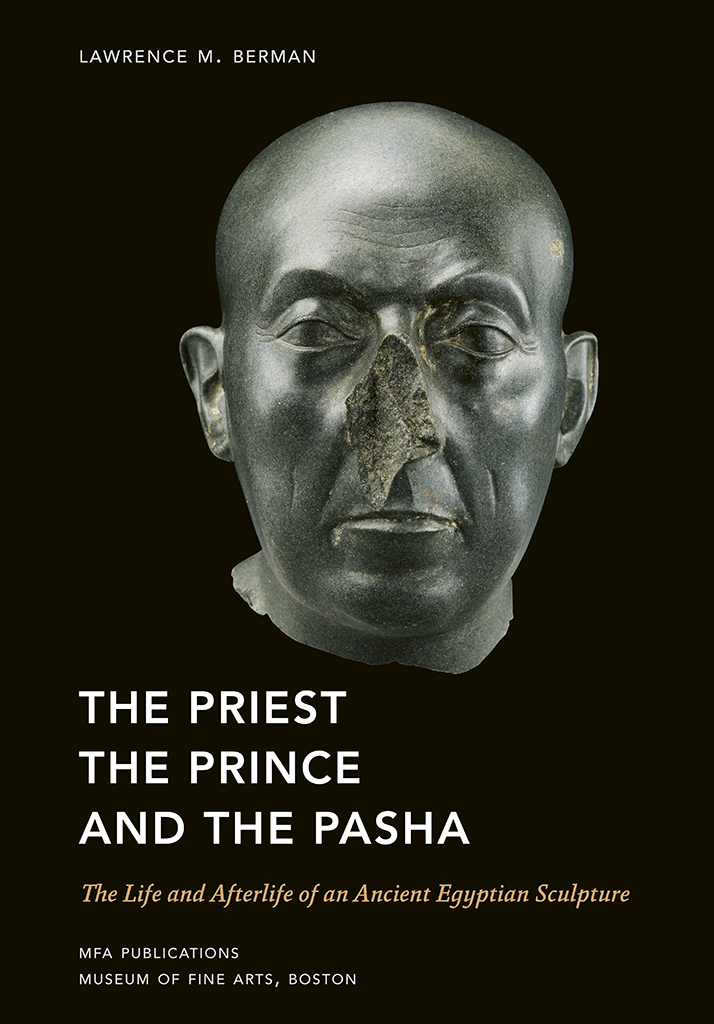

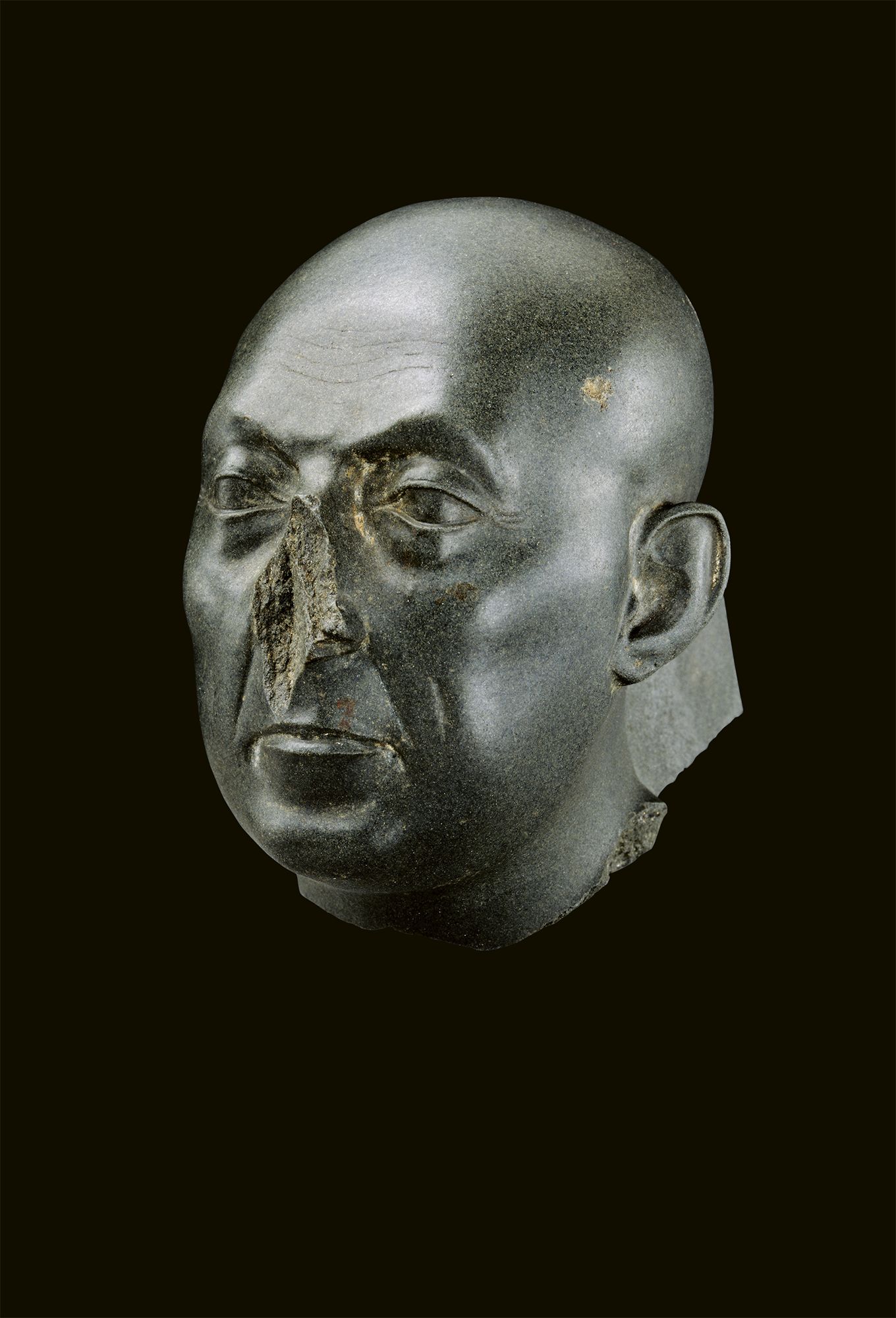

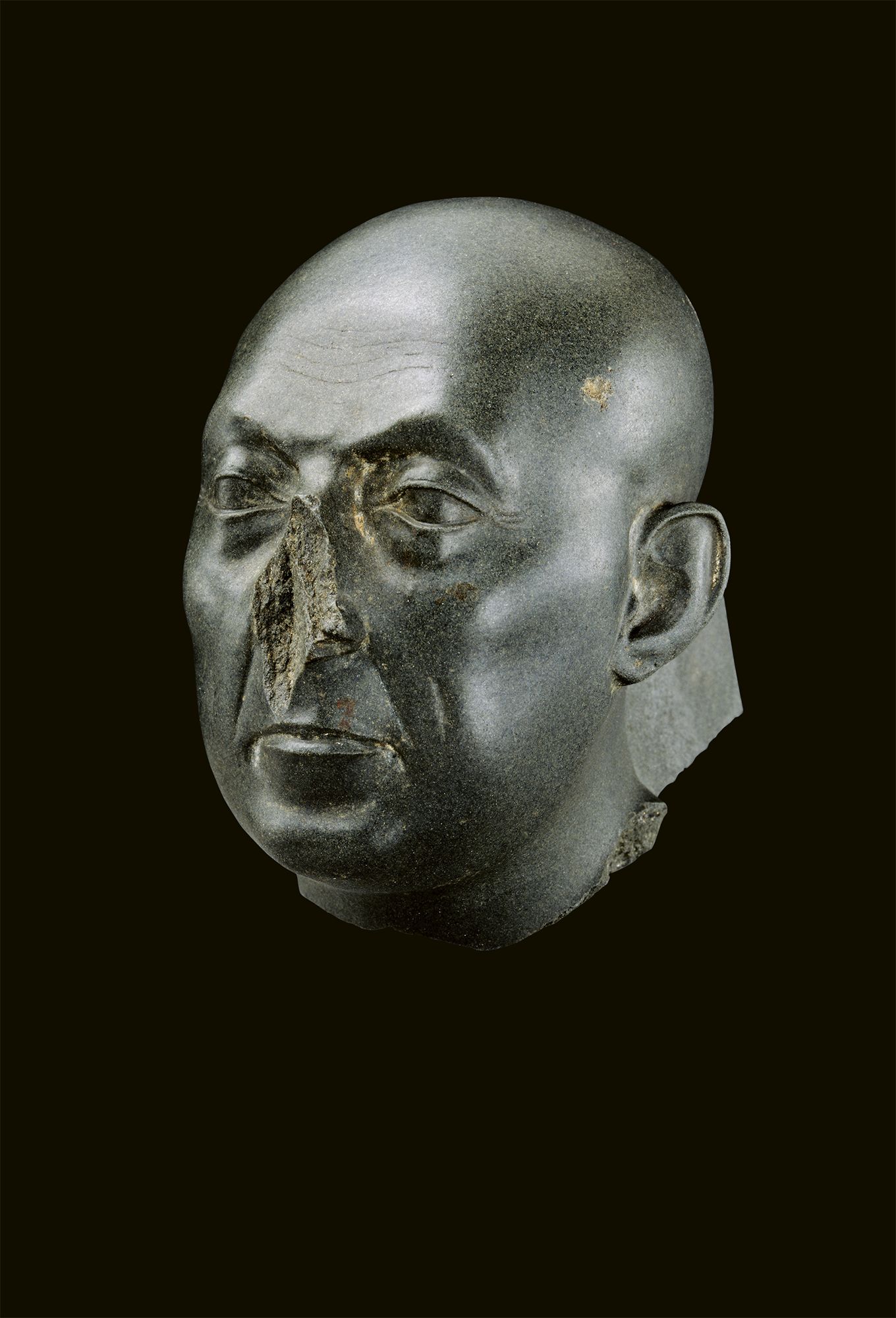

1. Head of a Priest (The Boston Green Head).

In 1904, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, acquired a small portrait head of an old man, broken off from a statue, in fine, hard, dark gray-green stone. The head is a masterpiece, beautifully carved, the features wonderfully lifelike and individual. Parallel light wavy lines indicate the furrows of the mans brow, and crows feet radiate from the outer corners of his eyes. The top of his nose has a pronounced bony ridge. The nose itself is gone. From the spring at the bridge, it clearly must have been a large and prominent featurea pity, as its loss is the sole significant damage the head has suffered. Deep creases run from the edges of his nose to the corners of his mouth. Thin lips and a downturned mouth impart a feeling of strength and determination. Details such as the slight wart on his left cheek and a second, shorter crease below it further enhance the realism of the features. Most remarkable of all is the sense of skin and bone, the bumps and shallows of the skull, the heavy arched brows, and roundness of the eyeballs set deep in their sockets, the delicacy of the lids, the prominent cheekbones, hollow cheeks, and slightly saggy jowls.

So lifelike is the artists rendition that it is natural to assume that the portrait faithfully captures the subjects distinctive facial features. In truth, we will never know. The ancient Egyptians did not make statues just to admire them as works of art. Statues served a specific religious purpose in tomb or temple, as places where the gods and the spirits of the dead could reside. The ritual of opening of the mouth, in which a priest wearing a leopard skin touched the statue with a carpenters adze, brought the statues senses to life and enabled the spirit inside to receive offerings of food and drink in perpetuity. The same ceremony was performed on statues of deities and on wrapped mummies. This religious function did not preclude portraiture. The Egyptians seem to have been capable of making individual portraits and in some periods this was considered desirable, even mandatory. Statues of King Menkaura (reigned 24902472 BC) are a case in point. The king is consistently shown with bulging eyes, puffy cheeks, a bulbous nose, and drooping lower lip.

The remains of the back pillara peculiar feature of ancient Egyptian sculpturewith hieroglyphic inscription leaves no doubt about the Egyptian origin of the piece. The stone itself tells as much. Often misidentified as basalt, schist, or slate, it is in fact graywacke from the Wadi Hammamat quarry in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, about halfway between Koptos and Quseir along one of the main routes from the Nile to the Red Sea.

It was immediately apparent that the head dated to the Late Period, but it has been placed in various eras during that seven-hundred-year span from the Kushite invasion to the end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty: the Saite Period (7th6th century BC), Dynasty 30 (4th century BC), and the mid-Ptolemaic Dynasty (late 3rdearly 2nd century BC).

Although only ten-and-a-half centimeters high (a little more than four inches), the head makes a monumental impression. When complete, the figure was probably standing or kneeling. Most Egyptian statues in the Late Period were made to be placed in temples rather than tombs. Our man was probably shown holding an attribute appropriate to the temple setting such as a statue of a deity, or a naos , or shrine, containing the image of a deity, as an emblem of his piety. If standing, the figure would have been about 71 centimeters (28 inches) high; if kneeling, about 44 centimeters (17 inches) high, to which one would have to add up to 2 inches for the height of the integral base.

Our only clue to our subjects identity is his coiffure, or rather, the lack of one. Egyptian priests were required to shave their heads for reasons of ritual purity. Although not all priests appear shaven-headed in Egyptian sculpture, most statues of shaven-headed men represent priests. The trapezoidal top of the back pillar preserves the name of a funerary deity worshipped in Memphis, Ptah-Sokar, the beginning of a prayer that would have continued down the pillar to the base of the statue. The complete inscription would have included, at the very least, the subjects name and occupation. The base might also have been inscribed with another prayer, perhaps including additional titles, the name of a family member, orif we were luckyeven a snippet of historical information. If he was holding a naos , that too may have been inscribed. As it is, for lack of anything better, the piece is known worldwide as the Boston Green Head, after the color of the stone and the place where it now resides. Under that name it has become world famous.

The head has, moreover, a fascinating modern history. It was discovered in 1857 by Auguste Mariette at the Saqqara Serapeum. Just seven years earlier, the young French Egyptologist had discovered the tombs of the sacred Apis bulls, one of the most sensational discoveries in the history of Egyptology. Its first modern owner was the notorious Prince Plon-Plon, nephew of Napoleon I and first cousin of Napoleon III, who kept it in his Pompeian House in Paris. It came to the MFA via Edward Perry Warren, a Bostonian expatriate collector who transformed the museums holdings of classical art from an assembly of plaster casts to Americas premier collection of Greek and Roman originals. Through these and other individuals, the story of the Boston Green Head reaches back to the beginnings of Egyptian archeology. The successive stages of that history reflect the reception of Egyptian art in the modern era. That story is the subject of this book.

THE ARCHAEOLOGIST

2. Portrait of Auguste Mariette by Thodule Charles Devria, 1859. The archaeologist, 37 years old at the time of this drawing, had recently been appointed director of Egyptian antiquities.

On October 2, 1850, a young French Egyptologist named Auguste Mariette disembarked at Alexandria. He was twenty-nine years old. The French Government had commissioned him to visit the Coptic monasteries of Egypt and make an inventory of the manuscripts preserved in their libraries. It was his first visit to Egypt, and he was supposed to stay six months. Mariette returned to France four years later a famous man, having made one of the greatest finds in the history of Egyptology: the Serapeum of Memphis and the catacombs of the sacred Apis bulls. He sent back to France some six thousand objectsstatues, steles, bronzes, jewelry, funerary equipmentdating from the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic Dynasty. These and other discoveries would ultimately lead to Mariettes appointment as Egypts first director of antiquities. Along the way he would also discover a small head of a priest in green stone.

Franois Auguste Ferdinand Mariette was born at Boulogne-sur-Mer, on the English Channel, on February 11, 1821. As a youth he showed a talent for drawing; in 1839, at the age of eighteen, he went over to England, where for a year he taught French and drawing and then tried his hand at making designs for a ribbon manufacturer in Coventry. In 1841 he returned to Boulogne to resume his education, and in six months received his bachelors degree with honors at the University of Douai. He then accepted a teaching position at his old middle school in Boulogne, where he put his artistic talents to use designing and painting scenery for school theatrical productions. But he was increasingly drawn to journalism and wrote on a variety of topics for the local press: literary sketches, reviews, investigations into local history, even poetry. He became the editor of a local newspaper, LAnnotateur boulonnais .