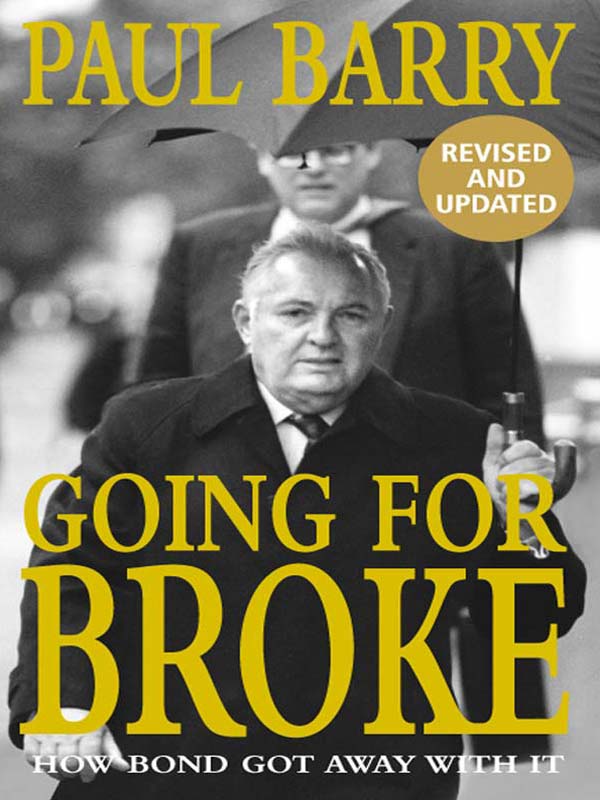

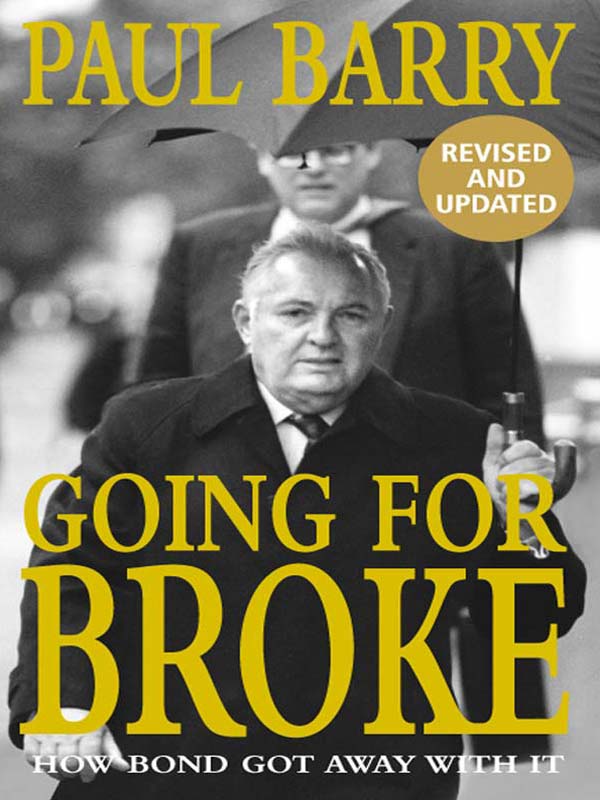

About the book

Everyone has a Bond story. This is the one you havent heard

Once upon a time Alan Bond was a hero - the man who won the Americas Cup for Australia, the poor immigrant turned sign writer who became a billionaire, the Aussie battler made good.

Then came a controversial expose by investigative journalist Paul Barry on ABCs Four Corners . This explosive portrait led to Barrys bestselling The Rise and Fall of Alan Bond and soon afterwards the house of cards collapsed, Bond was made bankrupt and sent to jail.

Now Bond is back, after spending less than three and a half years of his sentence for defrauding Bell resources of more than $1200 million - roughly one day in prison for every one million dollars shareholders lost.

In Going For Broke , Paul Barry does what no one else has been able to do: show how Bond stashed his fortune overseas, and prove that if your pockets are deep enough and your lawyers good enough, you can get away with almost anything - as long as you go for broke.

Going For Broke reads like a thriller, full of cloaks and daggers, car chases, courtroom dramas, larger than life villains and heroes - and its all true.

This is a story that had to be told. And no one else can tell it like Paul Barry.

Contents

For all honest Australians

Prologue

A rape, a rape,

You have ravished justice.

John Webster, 1612

3 May 1994

Its three years since Bonds business empire finally collapsed with debts of around $5 billion. And Alan has brought sandwiches for lunch.

Theyre in a green plastic bag he clutches in the dock. The press are impressed. Poor old Bondy.

Hes sitting like a zombie, staring into space, popping the occasional pill, as if hes nigh on brain dead. Were in the Federal Court in Sydney, and his interrogator is asking about bank accounts in Switzerland, companies in Panama and an accountants office in Jersey. He seems surprised that the questions are for him.

On occasion, he pauses for a minute, then asks for the question to be repeated. Hes trying hard, but he keeps on losing the plot. The trouble is he cant recall. There were so many companies, it was so long ago, and hes not been well.

He shuffles out of court, a small figure in a crumpled raincoat, bent and pale. A shadow of his former self.

Round a couple of corners, hes out of sight of the pursuing press. He steals a look, straightens up and tosses the bag away.

Later, hes at the Sheraton Wentworth, making the phones run hot. Hes calling Switzerland, Singapore and the USA. Dealing, dealing. Doing business.

The next day, I decide to test his memory. Surely no man can forget whether he has millions of dollars overseas. Surely this is an act?

I catch him walking up the street to the Federal Court and hand him a business card. Im Paul Barry from Four Corners . Remember me? He stamps on it, dances on it, grinds it into the pavement, and tells me to keep away. Keep right away.

So you do remember me, I say, you do remember me.

Back in the court, the questions continue. Bank accounts in London in the name of A. Bond, transfers to Switzerland in 1989, a few million dollars here, a few more million there. No. It doesnt ring a bell to Bondy. He cant recall a thing.

15 April 1995

One year later, and its just like old times. Australias greatest salesman is back with his 10,000 kilowatt smile. His skin is glossy, and hes rude with health. Hes plump, shiny and prosperous in white tie and tails. Hes puffed up with pride like a black-and-white bullfrog.

If he ever had brain damage, hes forgotten it now.

Outside Sydneys Museum of Contemporary Art, crowds of reporters, photographers and camera crews push and jostle to get close to Alan Bonds new bride. He is marrying a beautiful woman sixteen years younger than him. He has escaped from bankruptcy with the bulk of his fortune intact.

He has a second marriage, a second chance, a second coming. Good ol Bondy is back in business. Hes a winner again.

One has to say, he looks better in this role than when hes being hounded by those reptiles of the press. Adulation suits him so much more. He has always been puzzled by criticism, pained by the barbs of those who dont believe. Its been one of his greatest assets, the unshakeable conviction that hes done nothing wrong.

It can be hard not to admire someone so utterly devoid of guilt and shame, so completely unstoppable in the face of adversity, so consummately good at getting away with it. And as he likes to tell everyone, at least he stayed to face the music.

But there is another view of what Bond has achieved by his remarkable escape from the wreckage of his empire. And it is this. He has made a monkey out of the law and brought the legal system into disrepute. He has shown in the most public way possible that if your pockets are deep enough and your lawyers good enough, you can tie the system in knots forever, or at least until the most tenacious and bloody-minded pursuers give up. Nerve, stamina, self-belief, and access to a stash of cash, are all it takes. As long as you go for broke.

This is the story of how the bankruptcy laws of Australia failed to get hold of Alan Bonds fortune. And how they will always fail to catch people like Skase and Bond.

Its also a story about a man whose incredible resilience is, sadly, far greater than his respect for the truth.

Oh Lucky Man

If the bankrupt be convicted, he shall be set upon the pillory in some public place for the space of two hours, and have one of his ears cut off.

Bankruptcy Act 1623

Alan Bond is lucky he didnt go bust 150 years ago, because creditors in those days had the right to lock debtors in jail and throw away the key. The rules then were simple. If you borrowed money, you had to pay it back. Full stop.

There were no compromises, no settlements, no lengthy court battles, and no living high on the hog while debts remained unpaid. And the mere fact that court proceedings had started was enough for a creditor to have the debtor arrested by the sheriff, so that he did not abscond.

Londons notorious Newgate prison was full of such wretched people who often rotted inside for years over debts as small as a few shillings. Sometimes they died there, because if they couldnt pay what they owed, they stayed behind bars until their creditors decided to release them if they ever did.

Once jailed, there was also no guarantee that these poor debtors wouldnt starve to death, as an English judge once reminded an unfortunate subject in passing judgement:

Neither the plaintiff nor the sheriff is bound to give him meat or drink If he has no goods, he shall live off the charity of others, and if others give him nothing, let him die in the name of God for his presumption and ill-behaviour brought him to that imprisonment.

It was all a world away from our current lax attitude to credit. In those days, people who ran up debts that they couldnt pay were regarded quite simply as criminals.

Conditions in the jails were horrendous, with no attempt to segregate by sex or by gravity of the crime. And since many prisons were owned privately and run for profit, they typically demanded payment from their inmates for the most basic comfort. At Newgate, for example, there was an entrance fee of three shillings, a weekly rent of two shillings and sixpence, and a further weekly payment of one shilling and sixpence to share a straw mattress with another prisoner. In the debtors section, where by definition no one had money to purchase such things, you fought for floor space and scraps of food with murderers, rapists, footpads and anyone else who happened to be there. The inmates at Newgate called the debtors section Tangier, because it was reminiscent of the suffering inflicted on British sailors by Arab pirates off the Barbary Coast.