Contents

Guide

ALSO BY SAMANTH SUBRAMANIAN

This Divided Island: Life, Death, and the Sri Lankan War

Following Fish: Travels around the Indian Coast

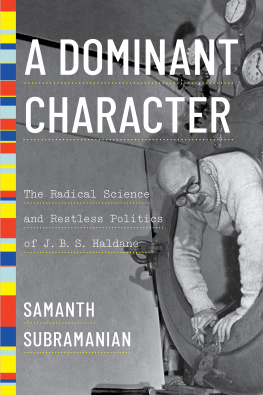

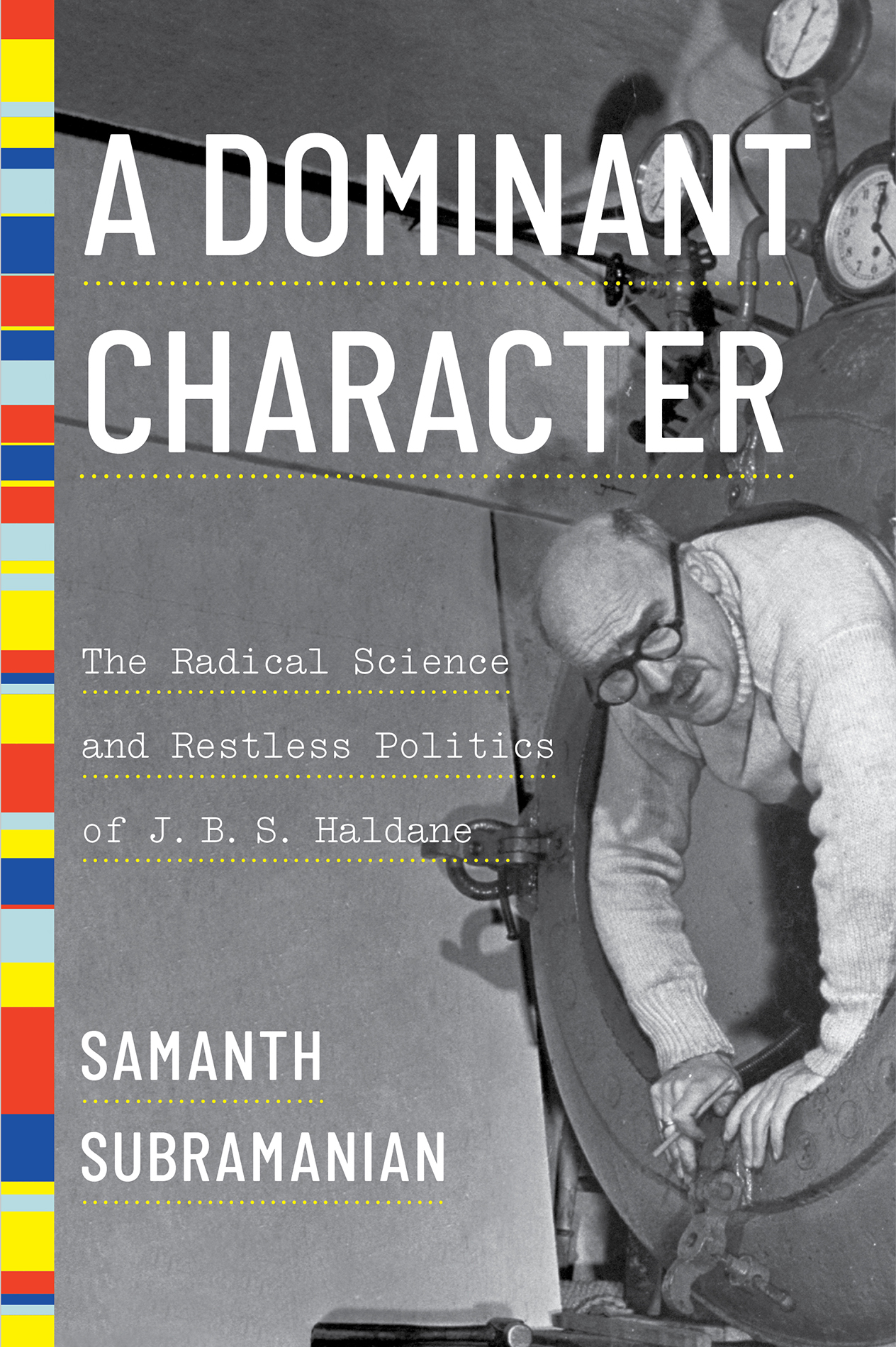

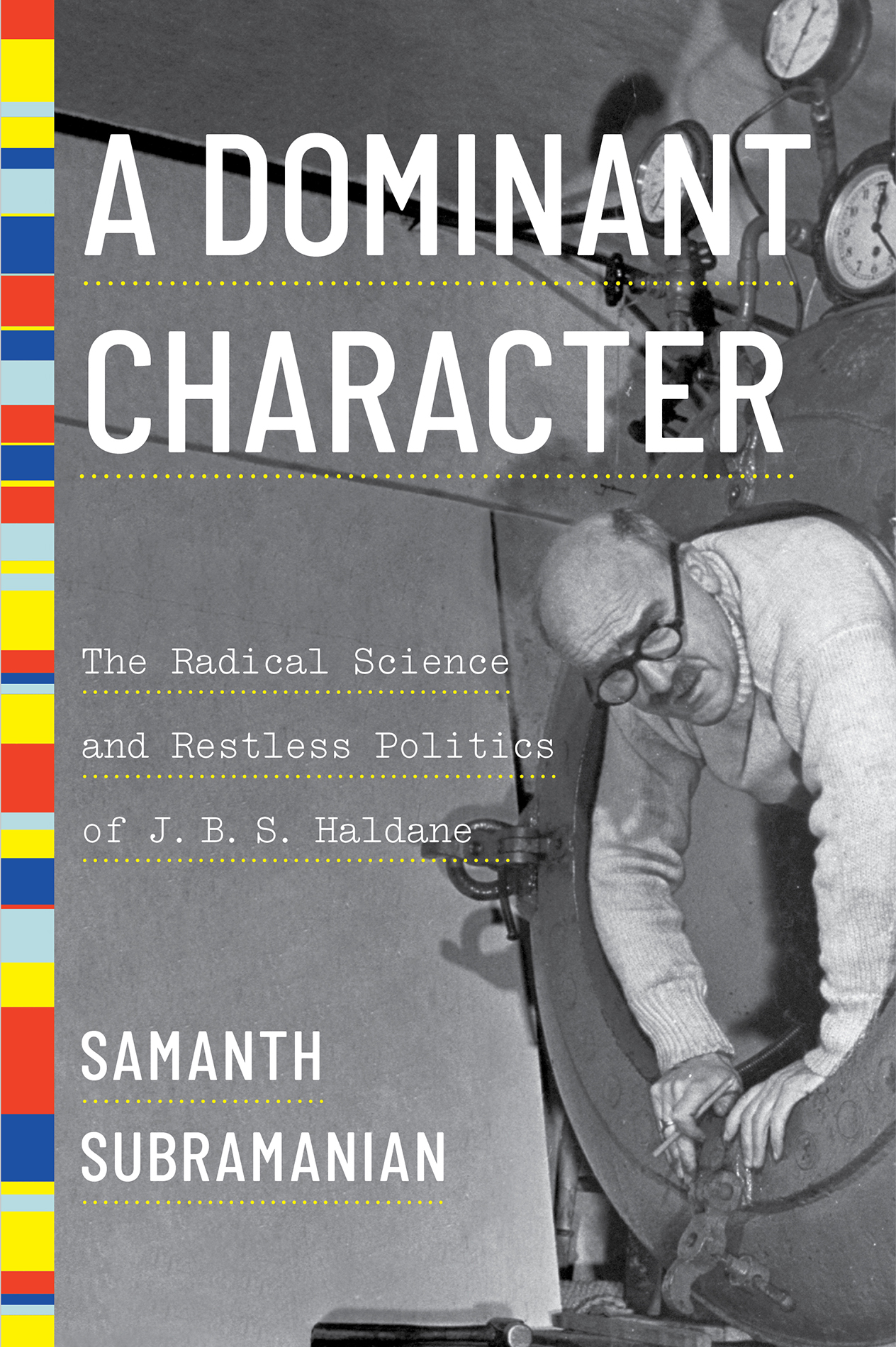

A

Dominant

Character

The Radical Science

and Restless Politics

of J. B. S. Haldane

Samanth

Subramanian

Copyright 2019 by Samanth Subramanian

First American Edition 2020

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Yang Kim

Jacket photograph: Hans Wild / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

Book design by Lisa Buckley

Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-0-393-63424-2

ISBN 978-0-393-63425-9 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Padma,

the most patient recipient imaginable

of a writers daily bulletins of torture

Suffer.

The family motto of the Haldane clan

Pathei-mathos (We suffer into knowledge).

Aeschylus, Agamemnon

Contents

A

Dominant

Character

The

Scientific

Method

1.

THE LETTER ARRIVED UNSOLICITED, like thousands of others. A retired chemist in Surrey had taken up plant genetics and set himself an immodest task: to improve the yield of his plants by a process that could then be applied by any farmer anywhere in the world. Now, in July 1948, he thought hed cracked it. His flax plants were producing 12 or 14 seeds in each pod, instead of the usual 10a bumper strain for flaxseed oil. The results seem beyond doubt, he wrote in his letter, after two and a half pages of jumbled description. He had read J. B. S. Haldanes essay Scientific Research for Amateurs. Would Haldane, as a renowned geneticist, be interested in this radical piece of amateur research?

Haldane wrote back. He nearly always did, even though he hated to be bothered by correspondence. His letters piled up around his various offices over the years: in Cambridge in the 1920s, in University College London until the 1950s, in Calcutta and Bhubaneswar thereafter. Some letters went missing, sinking under the flotsam that occupied these offices: notebooks, journals, Haldanes own papers on genetics and biometry, reprints of papers by other scientists, pamphlets, issues of the Daily Worker . If the letters bobbed back up to the surface, they were rescued. Haldane would first scrawl his response, often on some piece of paper on which he had been working out equations. Then his secretary typed it up. Which was just as well, because his handwriting resembled ants somersaulting through snow.

Dear Sir, Haldane wrote, Thank you for your letter. The chemists results seemed striking, but Haldane needed more: fuller details of the techniques he used and the results he obtained. You will realise that an account is useless unless it is so worded that others can repeat the work. This forms the kernel of the scientific method: that researchers elsewhere be able to replicate experiments and derive identical results. Science is held up by principles, and these principles have to be inherent in every place, not just in an amateur horticulturists patch of Surrey earth.

Haldane never shrank from exalting the scientific method, even in casual correspondence. Science advances by successive improvements in former theories, he wrote once to a man who sent him a hollow hypothesis about how thoroughbred racehorses inherited their coat colors. If they are wrongthe former theories, he meantthe reasons for rejecting them should be stated. If they are right, this should be acknowledged. To a W. Hague of Kingswood Cottages, London, who wished to alert the world to his discovery of a new law of nature, Haldane replied: The test for a new law of nature is this. Does it enable you to predict or control events which could not be predicted or controlled before? What is wanted... is a set of repeatable experiments which will go one way if it is true, and another way if it is not. The custom of accuracy in statement is essential, Haldane thought; it is, in fact, desirable to be pedantic. A scientist no doubt needed imagination to sense what nature hides, but when it came time to test and publish, Haldane considered it wise to heed Francis Bacon, to buckle and bow the mind to the procedures of science.

Restraint was not Haldanes style. He was a man armed with infinite provocations, and a grouch besides, his bluntness shading quickly into rude hostility. A journalist described him as a large woolly rhinoceros of uncertain temper. Even with friends, Haldane could be pungent in his remarks if something smelled like bad science. In 1953, Hans Kalmus sent Haldane a manuscript of his new book on human genetics. Kalmus was a longtime colleague and a protg of sorts, a Czech refugee who had, with Haldanes help, found work at University College just before the Second World War. None of these personal ties softened Haldanes assessment of the manuscript: It ought not to be published. He listed some errors, then added: I could go on indefinitely. The proposed book would not only harm Kalmus but the science of genetics itself. You would be better advised, if this is possible, to go back to experimental biology, he wrote, rather than to continue to work in human genetics.

If Haldane was merciless with others, he demanded similar rigor of himself. His career overlapped tidily with the bloom of genetics as a field of study and with the effort to discover the role of the gene in Charles Darwins theory of evolution. Genetics grew severally studded with Haldanes contributions. He demonstrated, for the first time in mammals, the mechanism of genetic linkage, by which two genes that reside near each other on a chromosome tend also to be inherited together. (He wrote up parts of this paper while serving in the trenches during the First World War.) He mapped the genes for hemophilia and color blindness. He introduced a theory for how life began on Earth. His speculations on ectogenesis forecast the development of in vitro fertilization.

His most important work came in a series of 10 papers, written between 1924 and 1933, in which he subjected evolution to the unflinching stare of statistics. The papers modeled the processes of natural selection and estimated rates at which gene mutations develop and spread through a population. He was gaining the measure of life itself. The stringency of statistics delighted Haldane. Everyone should know more mathematics, he always thought. Numbers were so satisfyingly precise, equations so universal. How well they ministered to the scientific method!

Had Haldane done just this and little else, he would have been an important scientistnot as revolutionary as Einstein, perhaps, and not associated for perpetuity like Watson and Crick with a single, shining discovery, but certainly among the few who altered their field beyond recognition, pushing it forward paper by paper. This is how science progresses most of the time, after all: through the accretive power of daily work, through meat-and-potatoes research. What made Haldane one of the most famous scientists of his age, though, was not just his science but also his writing and his politicsthe first clear and illuminating, the second unbending and forthright, both deeply attractive during a time of shifting, murky moralities.