Paul Robert Walker - The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World

Here you can read online Paul Robert Walker - The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti

Changed the Art World

A mia zia Sonja e alla famiglia Italiana che mi ha dato: Jens, Giuseppina, Alessandro, e Sonja; Dorian, Gianfranco, Pippo, Papik, e Paolo.

To my Aunt Sonja and the Italian family she gave me:

Jens, Giuseppina, Alessandro, and Sonja;

Dorian, Gianfranco, Pippo, Papik, and Paolo.

Only the artist, not the fool

Discovers that which nature hides.

Filippo Brunelleschi, 1425

Epigraph

Preface

1. Plague of the Bianchi

2. Competition for the Doors

3. Beautiful Works

4. The Committee

5. Two Fathers

6. The Fat Woodworker

7. Speaking Statues

8. Ingenious Man

9. Competition for the Dome

10. The Art of Building

11. Excellent Master

12. Sonnet Wars

13. Big Thomas

14. The Catasto

15. Flood of Lucca

16. Bad Acts

17. All of Tuscany

18. Filippo Architetto

19. At the Mirror

20. I, Lorenzo

Epilogue

Authors Note

Source Notes

Bibliography

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Paul Robert Walker

Copyright

About the Publisher

The world having for so long been without artists of lofty soul or inspired talent, heaven ordained that it should receive from the hand of Filippo the greatest, the tallest, and the finest edifice of ancient and modern times, demonstrating that Tuscan genius, although moribund, was not yet dead.

Vasari, Lives of the Artists

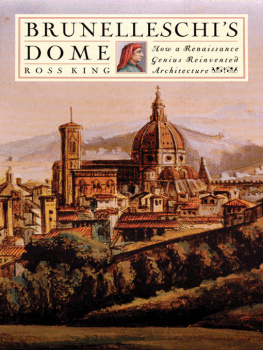

SOMETHING HAPPENED in Florence six hundred years ago, something so unique and miraculous that it changed our world forever. We call it the Renaissance, a rebirth of ancient art and learning. Yet it was more than a rebirth or rediscovery of ancient secrets; it was a first birth, the beginning of a modern consciousness, a modern way of seeing and representing the world around us. It was the defining moment for the societal role we call the artist. It was the beginning of Art with a capital A.

There had been art and artists before, of course: great lyrical, naturalistic art in ancient Greece and Rome; evocative, if limited, art in the Byzantine Empire and medieval Europe; a rough yet brilliant grasping for ancient lyricism and naturalism in the early 1300s. But what happened in Florence between 1399 and 1452, the first half of what the Italians call the Quattrocento, was nothing less than an artistic revolution. And the men who fired the first shots and led the charge for half a century were Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Their pupil Donatello marched beside them, and soon took the lead in his own chosen field, while a younger man called Masaccio later joined them and took the lead in his. Together, these four artists laid the groundwork for all who came after them, creating a new art with little to build upon except shadows of the past and the brilliant striving of their own creative spirits.

Hordes of tourists visit Florence every year, and it is safe to say that every one of them gazes in wonder at Brunelleschis dome: eight white marble ribs arching impossibly toward heaven, eight massive sections of masonry faced with red terra-cotta tile, topped with an elegant marble lantern against the pale blue Tuscan sky. They gather in front of the nearby church of John the Baptist, the Baptistery, and admire Ghibertis famous Paradise Doors, not knowing perhaps that the shiny panels are imperfect replicas. They search out Donatellos sculpture and perhaps they cross the Arno to see Masaccios frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel. Ironically, many miss Ghibertis other set of doors, on the north face of the Baptistery, for these are real, not so shiny, and still used as doors rather than displayed as art. Yet it was these doors and the competition to create them that gave birth to the Renaissance.

The idea of the competition as a turning point in the history of art was expressed by Lorenzo himself in the Commentaries, the first self-analytical literary work by a visual artist in the postclassical world. Lorenzo won the competition, so it was natural for him to see it as a defining moment, but even so, he was right and few critics in the last 550 years have challenged the fundamental idea. The real question is, to whom did this moment belong? Was it Lorenzos moment, as he maintained? Or did it rightfully belong to his rival, the man who didnt make the doorsFilippo Brunelleschi?

This latter idea was expressed in The Life of Brunelleschi, an extraordinary biography written during the 1480s, four decades after Brunelleschis death. The first full-length biography of an artist since Roman times, the Life, or Vita, is attributed by most scholars to Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, a mathematician who as a young man knew Brunelleschi as an old man. Manetti saw the competition as a youthful disappointment that forced Brunelleschi to follow a new and higher destiny as an architect and the leading force of the artistic Renaissance. It is Manetti who first sets forth the idea of a lifelong conflict between Filippo and Lorenzo, beginning with the competition for the doors, continuing through their work on the dome and beyond. For Manetti, Brunelleschi is a man who lost the battle but won the war. And with this, too, most modern critics would agree.

Manettis purpose is polemical, an attempt to defend his heros architectural style against what the author believed to be a compromise of Brunelleschis pure classicism. The Vita is full of detailed analysis of buildings, carefully pointing out those parts that can be attributed to Brunelleschi and those parts that were ruined by errors made by men who either were unable to understand the masters intentions or arrogantly thought they had better ideas. These passages are essential to the architectural historian, and they are generally quite accurate, for Manetti dabbled in architecture himself and saw these buildings under construction, a process that continued well after Brunelleschis death.

At the same time, the Vita is full of stories, wonderful tales that reveal much about Brunelleschis personality and the dynamics of the Florentine artistic scene in the early Quattrocento. Certain details of Manettis stories are contradicted by the documentary record, and this caused a backlash for a time, with scholars denigrating the biographical importance of the Vita. In recent decades, however, as more documents have come to light and more careful study has been applied to the buildings, it has become apparent that the essence, if not the details, of Manettis stories rings true. In a sense, the Vita is the Gospel of Brunelleschi, and Manetti saw his hero as a savior who rescued the artistic world from the depths of Gothic doldrums and gave it new life with a style alla Romana or allantica. This interpretation had as much to do with the values of Manettis time as it did with the reality of Brunelleschis art, but the stories have a more personal truth beyond such interpretation.

In 1550, almost seventy years after Manetti and over a century after the events he described, Giorgio Vasari included biographies of Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, and Masaccio in his first edition of Lives of the Artists. Considered the first artistic historian, Vasari is, in many cases, our earliest source for the life of a given artist. For Brunelleschi, however, Vasari essentially rewrote the Vita in more graceful narrative form, adding a few intriguing details that contain a kernel of truth and others that are patently absurd, while filling out the stories with invented dialogue and a new thematic emphasisthe idea of the artist as a pure being infused with God-given talent above the limits of everyday experience. Vasari drew this idea from personal contact with his own hero, Michelangelo, but he saw Brunelleschi, born a century before the brilliant sculptor, as cast in a similar mode, endowed with geniusso commanding that we can surely say he was sent by heaven to renew the art of architecture. Praising Brunelleschis contemporaries as well, Vasari saw them rightly as a generation of giants.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World»

Look at similar books to The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.