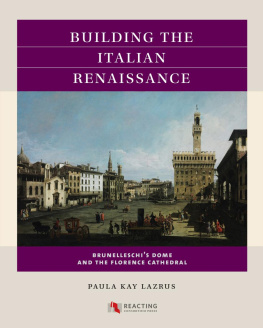

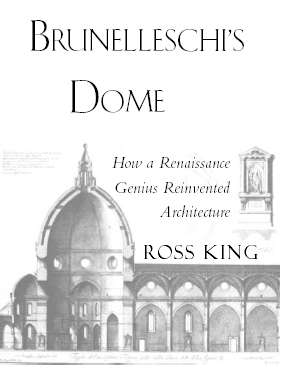

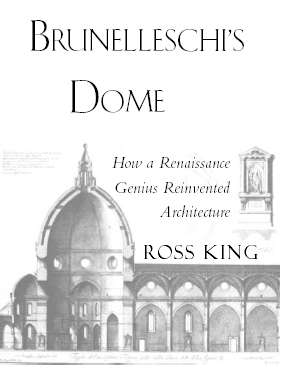

B RUNELLESCHI S

D OME

WALKER & COMPANY New York

Copyright 2000 by Ross King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in Great Britain in 2000 by Chatto & Windu

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA;

first published in the United States of America in 2000 by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Title page art is a section drawing of Santa Maria del Fiore by Giovanni Battista Nelli.

Brunelleschis dome: how a Renaissance genius reinvented architecture / Ross King.

ISBN 0-8027-9855-1

FOR MARK ASQUITH

AND

ANNE-MARIE RIGARD

C ONTENTS

I LLUSTRATIONS

The author and publisher are grateful for permission to reproduce illustrations in this book, and to Sarah Challis and Eugenio Battisti for their diagrams.

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to everyone who assisted with the research and writing of this book. I am indebted to Alta Macadam for reading the manuscript and sharing with me her encyclopedic knowledge of Florence, and to Sir Jack Zunz for his expertise in structural engineering and his understanding of the finer points of Brunelleschis technological achievement. A number of other people also read the manuscript in draft form and offered valuable advice: Mark Asquith, Ronald Jonkers, Sophie Oxenham, Anne-Marie Rigard, and Amir Ramezani. For help with translations I am grateful to Cristiana Papi and to my sister Maureen King. Thanks also to Maureen for tracking down a number of important periodical articles that would otherwise have been inaccessible to me. Sarah Challis executed diagrams for the text, while Margaret Duffy and Richard Mabey provided information in response to my queries. During the course of my research I was assisted on numerous occasions by the staffs of the British Library, the Bodleian Library, the London Library, and the Oxford University Engineering Science Library.

I also wish to thank my editors, Rebecca Carter and Roger Cazalet, both of whom saved me from errors in presentation and infelicities of style; my agent, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, whose steadfast support for the project was vital at every stage; and my German editor, Karl-Heinz Bittel, whose support has likewise kept the book afloat. Finally, I must record my thanks to the two people to whom the book is dedicated, Mark Asquith and Anne-Marie Rigard. I will always be grateful for their hospitality in London and companionship in Florence, but above all for their constant friendship.

B RUNELLESCHI S

D OME

A M ORE B EAUTIFUL

AND H ONOURABLE T EMPLE

O N A UGUST 19, 1418, a competition was announced in Florence, where the citys magnificent new cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore, had been under construction for more than a century:

Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome of the Cathedral under construction by the Opera del Duomo for armature, scaffold or other thing, or any lifting device pertaining to the construction and perfection of said cupola or vault shall do so before the end of the month of September. If the model be used he shall be entitled to a payment of 200 gold Florins.

Two hundred florins was a good deal of money more than a skilled craftsman could earn in two years of work and so the competition attracted the attention of carpenters, masons, and cabinetmakers from all across Tuscany. They had six weeks to build their models, draw their designs, or simply make suggestions how the dome of the cathedral might be built. Their proposals were intended to solve a variety of problems, including how a temporary wooden support network could be constructed to hold the domes masonry in place, and how sandstone and marble blocks each weighing several tons might be raised to its top. The Opera del Duomo the office of works in charge of the cathedral reassured all prospective competitors that their efforts would receive a friendly and trustworthy audience.

Already at work on the building site, which sprawled through the heart of Florence, were scores of other craftsmen: carters, bricklayers, leadbeaters, even cooks and men whose job it was to sell wine to the workers on their lunch breaks. From the piazza surrounding the cathedral the men could be seen carting bags of sand and lime, or else clambering about on wooden scaffolds and wickerwork platforms that rose above the neighboring rooftops like a great, untidy birds nest. Nearby, a forge for repairing their tools belched clouds of black smoke into the sky, and from dawn to dusk the air rang with the blows of the blacksmiths hammer and with the rumble of oxcarts and the shouting of orders.

Florence in the early 1400s still retained a rural aspect. Wheat fields, orchards, and vineyards could be found inside its walls, while flocks of sheep were driven bleating through the streets to the market near the Baptistery of San Giovanni. But the city also had a population of 50,000, roughly the same as Londons, and the new cathedral was intended to reflect its importance as a large and powerful mercantile city. Florence had become one of the most prosperous cities in Europe. Much of its wealth came from the wool industry started by the Umiliati monks soon after their arrival in the city in 1239. Bales of English wool the finest in the world were brought from monasteries in the Cotswolds to be washed in the river Arno, combed, spun into yarn, woven on wooden looms, then dyed beautiful colors: vermilion, made from cinnabar gathered on the shores of the Red Sea, or a brilliant yellow procured from the crocuses growing in meadows near the hilltop town of San Gimignano. The result was the most expensive and most sought-after cloth in Europe.

Because of this prosperity, Florence had undergone a building boom during the 1300s the like of which had not been seen in Italy since the time of the ancient Romans. Quarries of golden-brown sandstone were opened inside the city walls; sand from the river Arno, dredged and filtered after every flood, was used in the making of mortar, and gravel was harvested from the riverbed to fill in the walls of the dozens of new buildings that had begun springing up all over the city. These included churches, monasteries, and private palaces, as well as monumental structures such as a new ring of defensive walls to protect the city from invaders. Standing 20 feet high and running five miles in circumference, these fortifications, not finished until 1340, took more than fifty years to build. An imposing new town hall, the Palazzo Vecchio, had also been constructed, complete with a bell tower that stood more than 300 feet high. Another impressive tower was the cathedrals 280-foot campanile, with its bas-reliefs and multicolored encrustations of marble. Designed by the painter Giotto, it had been completed in 1359, after more than two decades of work.

Yet by 1418 what was by far the grandest building project in Florence had still to be completed. A replacement for the ancient and dilapidated church of Santa Reparata, the new cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore was intended to be one of the largest in Christendom. Entire forests had been requisitioned to provide timber for it, and huge slabs of marble were being transported along the Arno on flotillas of boats. From the outset its construction had as much to do with civic pride as religious faith: the cathedral was to be built, the Commune of Florence had stipulated, with the greatest lavishness and magnificence possible, and once completed it was to be a more beautiful and honourable temple than any in any other part of Tuscany. But it was clear that the builders faced major obstacles, and the closer the cathedral came to completion, the more difficult their task would become.