Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Also by Ross King

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Brunelleschis Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture

Michelangelo and the Popes Ceiling

The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism

Machiavelli: Philosopher of Power

Leonardo and the Last Supper

Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven

Florence: The Paintings and Frescoes, 12501743 (with Anja Grebe)

The Bookseller of Florence

The Story of the Manuscripts

That Illuminated the Renaissance

ROSS KING

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2021 by Ross King

Jacket design by Becca Fox Design

Jacket artwork: painting, portrait of Cardinal Bessarion by Joos (Justus)

van Ghent (c. 1435-c. 1480) and Pedro Berruguete (14501504)

RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NYl; hand-lettering by Rebeca Anaya;

spine Carolyn Jenkins/Alamy; back cover AF Fotografie/Alamy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

FIRST EDITION

Printed in Canada

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: April 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5852-9

eISBN 978-0-8021-5853-6

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Simonetta Brandolini dAdda

All evil is born from ignorance. Yet writers have illuminated the world, chasing away the darkness.

Vespasiano da Bisticci

Contents

Chapter 1

The Street of Booksellers

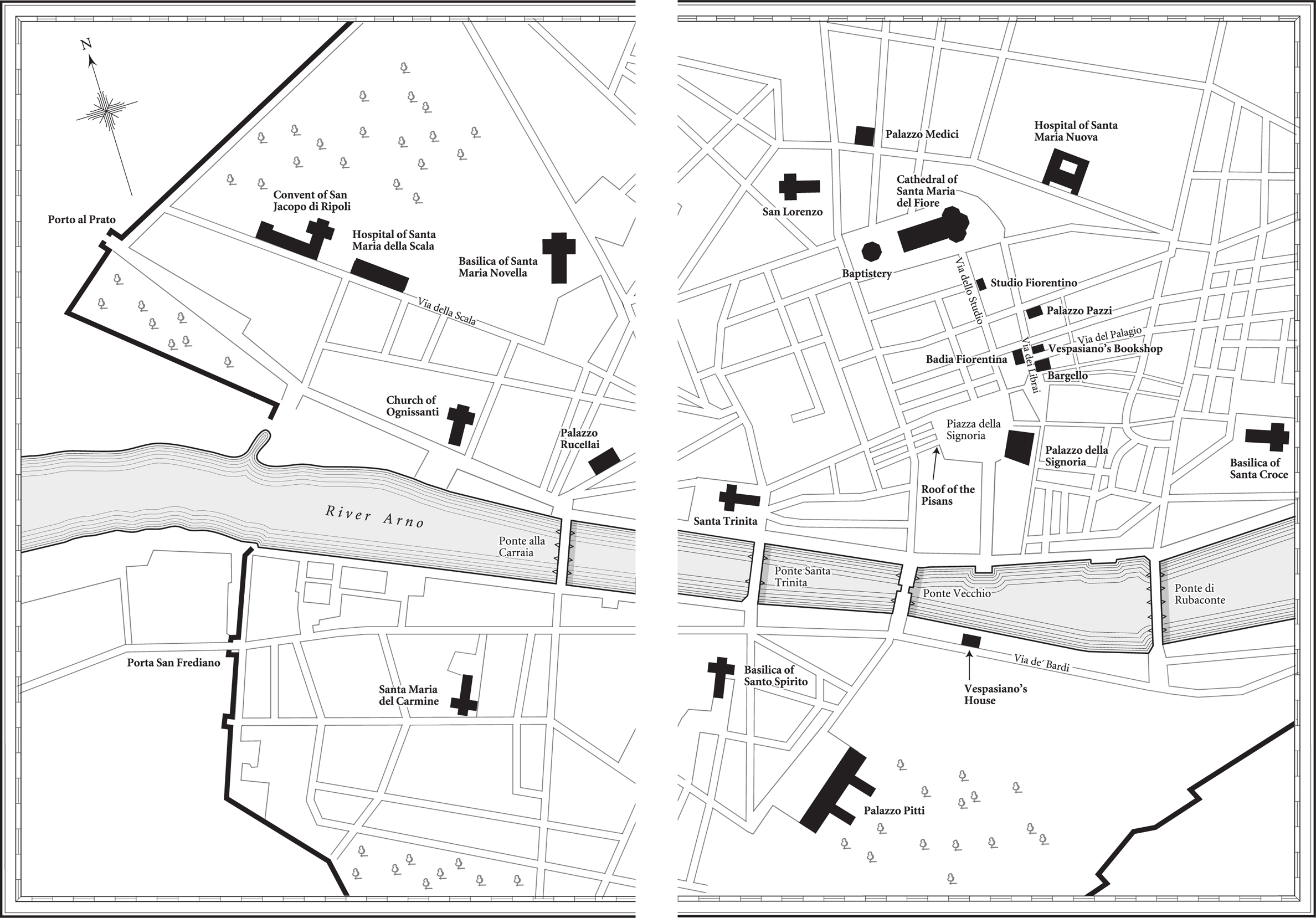

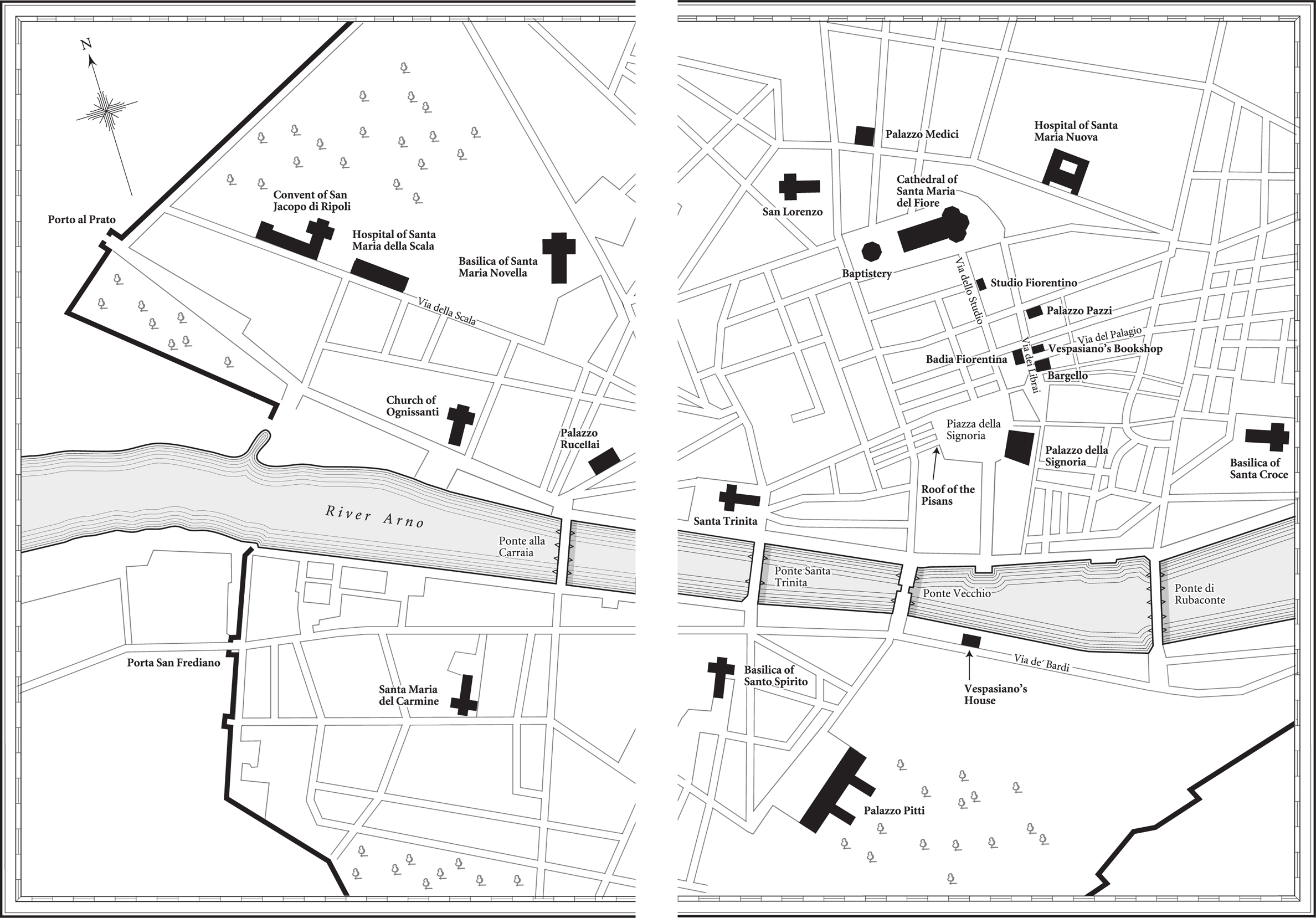

The Street of Booksellers, Via dei Librai, ran through the heart of Florence, midway between the town hall to the south and the cathedral to the north. In the 1430s the street was home to an assortment of tailors and cloth merchants, as well as a barrel maker, a barber, a butcher, a baker, a cheesemonger, several notaries, a manuscript illuminator, two painters who shared a workshop, and a pianellaioa maker of slippers. It took its name, however, from the shops of the many booksellers and stationers, known as cartolai, scattered along its narrow stretch.

In those days the Street of Booksellers was home to eight cartolai. They took their name from the fact that they sold paper (carta) of various sizes and qualities, which they procured from nearby papermills. They also stocked parchment, made from the skin of calves or goats and prepared by parchment makers, many of whose workshopswith their hides festering in wooden vatscould be found in neighboring streets. But cartolai offered far more extensive services than just selling paper and parchment: they produced and sold manuscripts. Customers could buy secondhand volumes from them or hire them to have a manuscript copied by a scribe, bound in leather or board, and, if they wished, illuminateddecorated with illustrations or designs in paint and gold leaf. Cartolai were at the very center of Florences manuscript trade, serving as booksellers, binders, stationers, illustrators, and publishers. An enterprising cartolaio might deal with everyone from scribes and miniaturists to parchment makers and goldbeaters, and sometimes even with authors themselves.

Bookmaking was a trade in which, like wool and banking, the Florentines excelled. The cartolai found a buoyant local market because many people in Florence purchased books. In Florence, more than anywhere else, large numbers of people could read and write, as many as seven in every ten adults. The literacy levels of other European cities, by contrast, languished at less than 25 percent.

One of the larger bookshops stood toward the north end of the Street of Booksellers, at its intersection with Via del Palagio, where the grim wall of the palace of Florences chief magistrate faced the elegant facade of an abbey known as the Badia. Since 1430 Michele Guarducci, the proprietor, had rented the premises from the abbeys monks for fifteen florins Each morning many of Florences most brilliant minds gathered on the corner beside this palazzo, only a few steps from Guarduccis shop, to discuss philosophy and literature. Florence was celebrated in those days for its writers, especially for its literary scholars and philosophers (from philosophos, lover of wisdom): men who expertly sifted and scrutinized the accumulated wisdom of the ages, especially the works of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Many of these texts, lost for centuries, had recently been rediscovered by Florentines such as Poggio Bracciolini, who, amid much rejoicing, had recovered long-lost works by Roman writers such as Cicero and Lucretius.

The Street of Booksellers, today part of Via del Proconsolo. The Bargello, with its tower, is on the left, and the entrance to the Badia is on the right.

Poggio was one of the lovers of wisdom who gathered on the street corner beside Guarduccis shop. Though he and his friends naturally browsed the shops of the cartolai in search of manuscripts, few of them, in the early 1430s, might have found much to tempt them in Guarduccis premises. He kept a talented illustrator on staff, but his lease described him as cartolaio e legatore, stationer and bookbinder, and he specialized not in obscure and enticing Greek and Latin works but, rather, in the humbler trade of binding manuscripts. Besides paper and parchment, his shop was therefore well supplied with clasps, studs, wooden boards, hammers, and nails, as well as piles of calfskin and velvet. The barking of hammers, the coughing of sawssuch were the sounds greeting anyone who entered his shop.

Things were about to change. In 1433 Guarducci hired a new assistant, an eleven-year-old boy named Vespasiano da Bisticci. So began Vespasianos long and astounding career as a maker of books and a merchant of knowledge. Soon Florences men of letters would be gathering inside the bookshop, not outside on the street corner. For in the world of the cartolai, of parchment and quills, of scribes hunched over writing desks, of elegant libraries with hefty, portentous tomes chained to benches, Vespasiano was destined to become what one lover of wisdom called