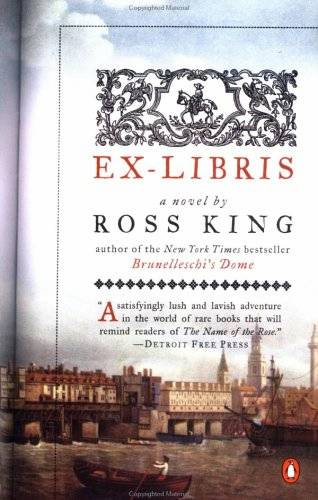

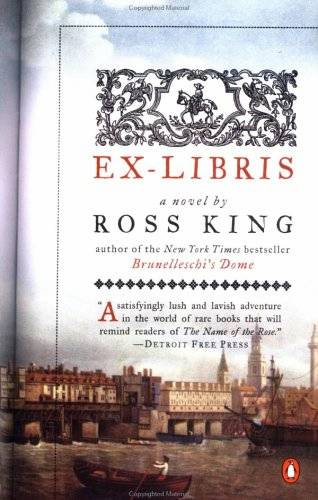

I am grateful to Dr. Bryan King for his assistance with matters alchemical and astronomical.

Me, poor man, my library

Was dukedom large enough

Shakespeare, The Tempest

Anyone wishing to purchase a book in London in the year 1660 had a choice of four areas. Ecclesiastical works could be bought from the booksellers in St. Paul's Churchyard, while the shops and stalls of Little Britain specialised in Greek and Latin volumes, and those on the western edge of Fleet Street stocked legal texts for the city's barristers and magistrates. The fourth place to look for a book-and by far the best-would have been on London Bridge.

In those days the gabled buildings on the ancient bridge housed a motley assortment of shops. Here were found two glovers, a swordmaker, two milliners, a tea merchant, a book binder, several shoemakers, as well as a manufacturer of silk parasols, an invention that had lately come into fashion. There was also, on the north end, the shop of a plummassier who sold brightly-coloured feathers for the crowns of beaver hats like that worn by the new king. Most of all, though, the bridge was home to fine booksellers-six of them in all by 1660. Because these shops were not stocked to suit the needs of vicars or lawyers, or anyone else in particular, they were more varied than those in the other three districts, so that almost everything ever scratched on to a parchment or printed and bound between covers could be found on their shelves. And the shop on London Bridge whose wares were the most varied of all stood halfway across, in Nonsuch House, where, above a green door and two sets of polished window-plates, hung a signboard whose weather-worn inscription read:

NONSUCH BOOKS

All Volumes Bought & Sold

Isaac Inchbold, Proprietor

I am Isaac Inchbold, Proprietor. By the summer of 1660 I had owned Nonsuch Books for some eighteen years. The bookshop itself, with its copiously furnished shelves on the ground floor and its cramped lodgings one twist of a turnpike stair above those, had resided on London Bridge-and in a corner of Nonsuch House, the most handsome of its buildings-for much longer: almost forty years. I had been apprenticed there in 1635, at the age of fourteen, after my father died during an outburst of plague and my mother, confronted shortly afterwards with his debts, helped herself to a cup of poison. The death of Mr. Smallpace, my master-also from the plague-coincided with the end of my apprenticeship and my entry as a freeman into the Company of Stationers. And so on that momentous day I became proprietor of Nonsuch Books, where I have lived ever since in the disorder of several thousand morocco- and buckram-bound companions.

Mine was a quiet and contemplative life among my walnut shelves. It was made up of a series of undisturbed routines modestly pursued. I was a man of wisdom and learning-or so I liked to think-but of dwarfish worldly experience. I knew everything about books, but little, I admit, of the world that bustled past outside my green door. I ventured into this alien sphere of churning wheels and puffing smoke and scurrying feet as seldom as circumstances permitted. By 1660 I had travelled barely more than two dozen leagues beyond the gates of London, and I rarely travelled much within London either, not if I could avoid it. While running simple errands I often became hopelessly confused in the maze of crowded, filthy streets that began twenty paces beyond the north gate of the bridge, and as I limped back to my shelves of books I would feel as if I were returning from exile. All of which-combined with nearsightedness, asthma and a club foot that lent me a lopsided gait-makes me, I suppose, an improbable agent in the events that are to follow.

What else must you know about me? I was unduly comfortable and content. I was entering my fortieth year with almost everything a man of my inclinations could ask for. Besides a prospering business, I had all of my teeth, most of my hair, very little grey in my beard, and a handsome, well-tended paunch on which I could balance a book while I sat hour after hour every evening in my favourite horsehair armchair. Each night an old woman named Margaret cooked my supper, and twice a week another poor wretch, Jane, scrubbed my dirty stockings. I had no wife. I had married as a young man, but my wife, Arabella, had died some years ago, five days after scratching her finger on a door-latch. Our world was a dangerous place. I had no children either. I had dutifully sired my share-four in all-but they too had died from one affliction or another and now lay buried alongside their mother in the outer churchyard of St. Magnus-the-Martyr, to which I still made weekly excursions with a bouquet from the stall of a flower-seller. I had neither hopes nor expectations of remarriage. My circumstances suited me uncommonly well.

What else? I lived alone except for my apprentice, Tom Monk, who was confined after the conclusion of business hours to the top floor of Nonsuch House, where he ate and slept in a chamber that was not much bigger than a cubbyhole. But Monk never complained. Nor, of course, did I. I was luckier than most of the 400,000 other souls crammed inside the walls of London or outside in the Liberties. My business provided me with 150 per year-a handsome sum in those days, especially for a man without either a family or tastes for the sensual pleasures so readily available in London. And no doubt my quiet and bookish idyll would have continued, no doubt my comfortable life would have remained intact and blissfully undisturbed until I took my place in the small rectangular plot reserved for me next to Arabella, had it not been for a peculiar summons delivered to my shop one day in the summer of 1660.

On that warm morning in July the door to an intricate and singular house creaked invitingly ajar. I who considered myself so wise and sceptical was then to proceed in ignorance along its dark arteries, stumbling through blind passages and secret chambers in which, these many years later, I still find myself searching in vain for a clue. It is easier to find a labyrinth, writes Comenius, than a guiding path. Yet every labyrinth is a circle that begins where it ends, as Boethius tells us, and ends where it begins. So it is that I must double back, retrace my false turns and, by unspooling this thread of words behind me, arrive once again at the place where, for me, the story of Sir Ambrose Plessington began.

***

The event to which I refer took place on a Tuesday morning in the first week of July. I well remember the date, for it was only a short time after King Charles II had returned from his exile in France to take the throne left empty when his father was beheaded by Cromwell and his cronies eleven years earlier. The day began like any other. I unbarred my wooden shutters, lowered my green awning into a soft breeze, and sent Tom Monk to the General Letter Office in Clock Lane. It was Monk's duty each morning to carry out the ashes from the grate, brush the floors, empty the chamber-pots, cleanse the sink and fetch the coal. But before he performed any of these tasks I sent him into Dowgate to call for my letters. I was most particular about my post, especially on Tuesdays, which was when the mail-bag from Paris arrived by packet-boat. When he finally returned, having dallied, as usual, along Thames Street on the way back, a copy of Shelton's translation of Don Quixote, the 1652 edition, was propped on my paunch. I looked up from the page and, adjusting my spectacles, squinted at the shape in the doorway. No spectacle-maker has ever been able to grind a pair of lenses thick enough to remedy my squinch-eyed stare. I marked my place with a forefinger and yawned.

Next page