Contents

Guide

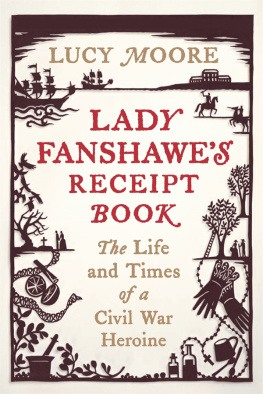

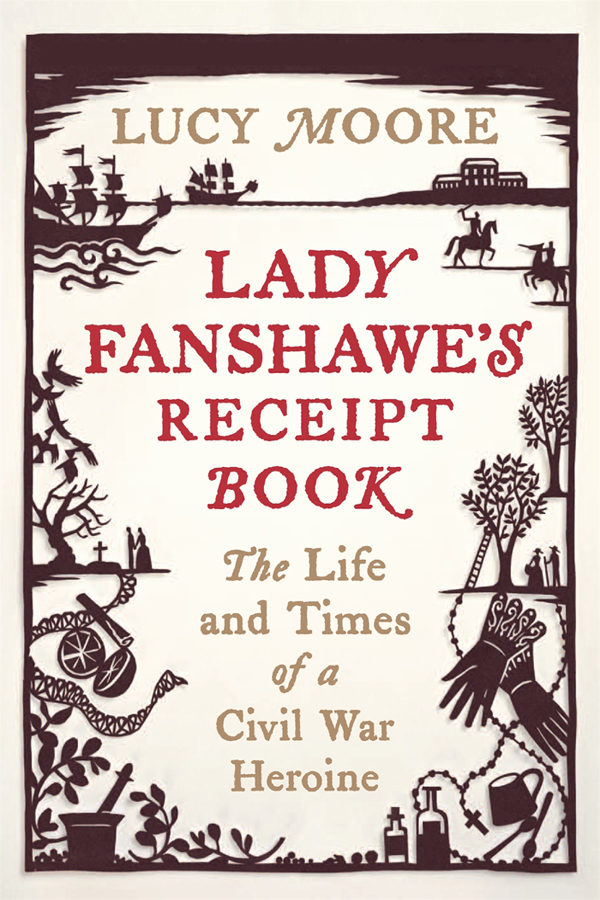

Lady Fanshawes Receipt Book

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Nijinsky: A Life

Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties

Liberty: The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France

Maharanis: The Lives and Times of Three Generations of Indian Princesses

Amphibious Thing: The Life of a Georgian Rake

The Thieves Opera: The Remarkable Lives and Deaths of Jonathan Wild, Thief-Taker, and Jack Sheppard, House-Breaker

Con Men and Cutpurses: Scenes from the Hogarthian Underworld

Lady Fanshawes Receipt Book

The Life & Times

of a

Civil War Heroine

LUCY MOORE

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2017 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Lucy Moore, 2017

The moral right of Lucy Moore to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78239 810 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 811 0

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 812 7

Text design and typesetting by Lindsay Nash

Endpaper image: Anns instructions for preparing and distilling herbs (MS7113, Wellcome Library)

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my sisters

Contents

Illustrations

COLOUR SECTION

BLACK AND WHITE ILLUSTRATIONS

Lady Fanshawes Receipt Book

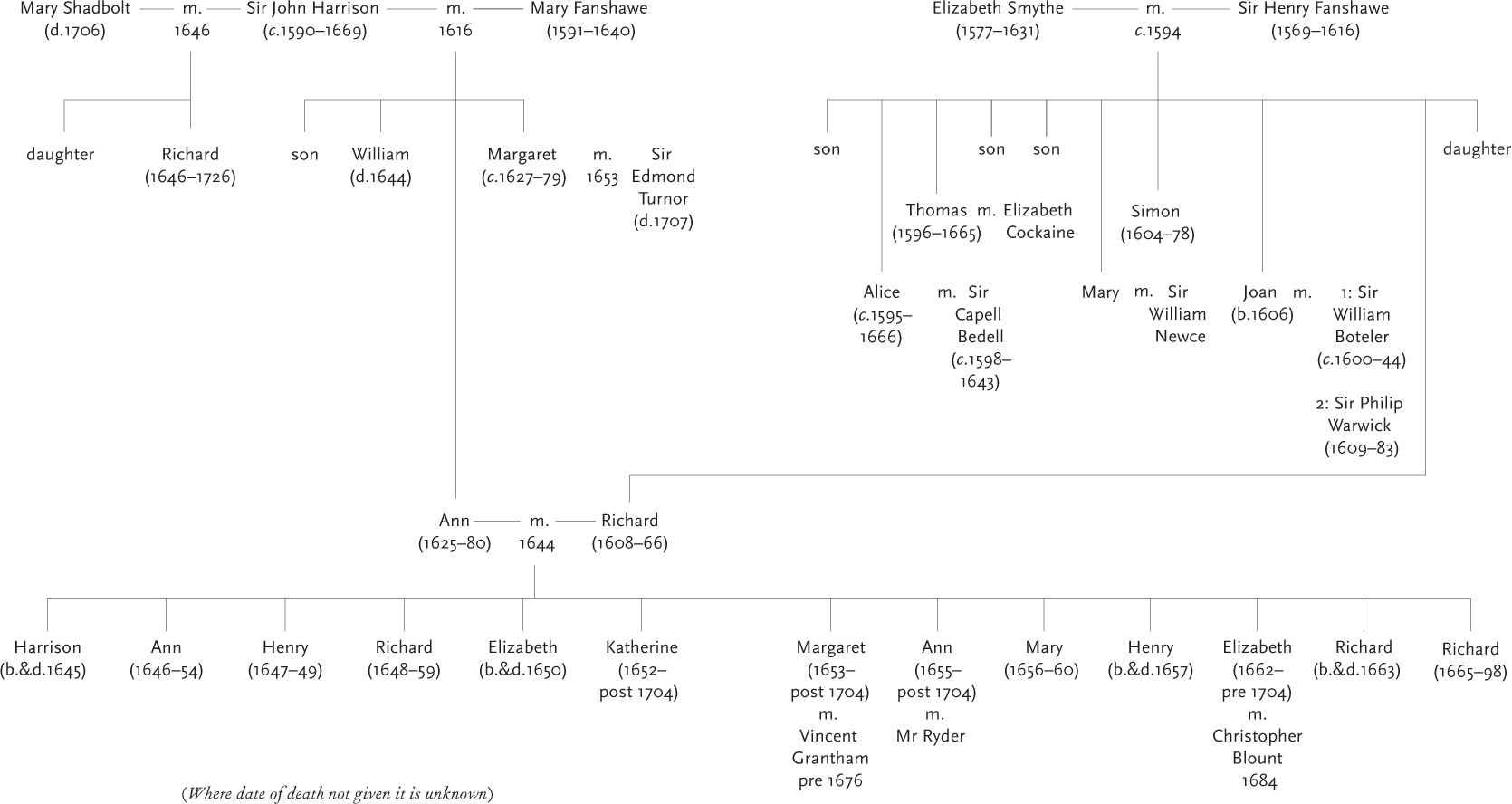

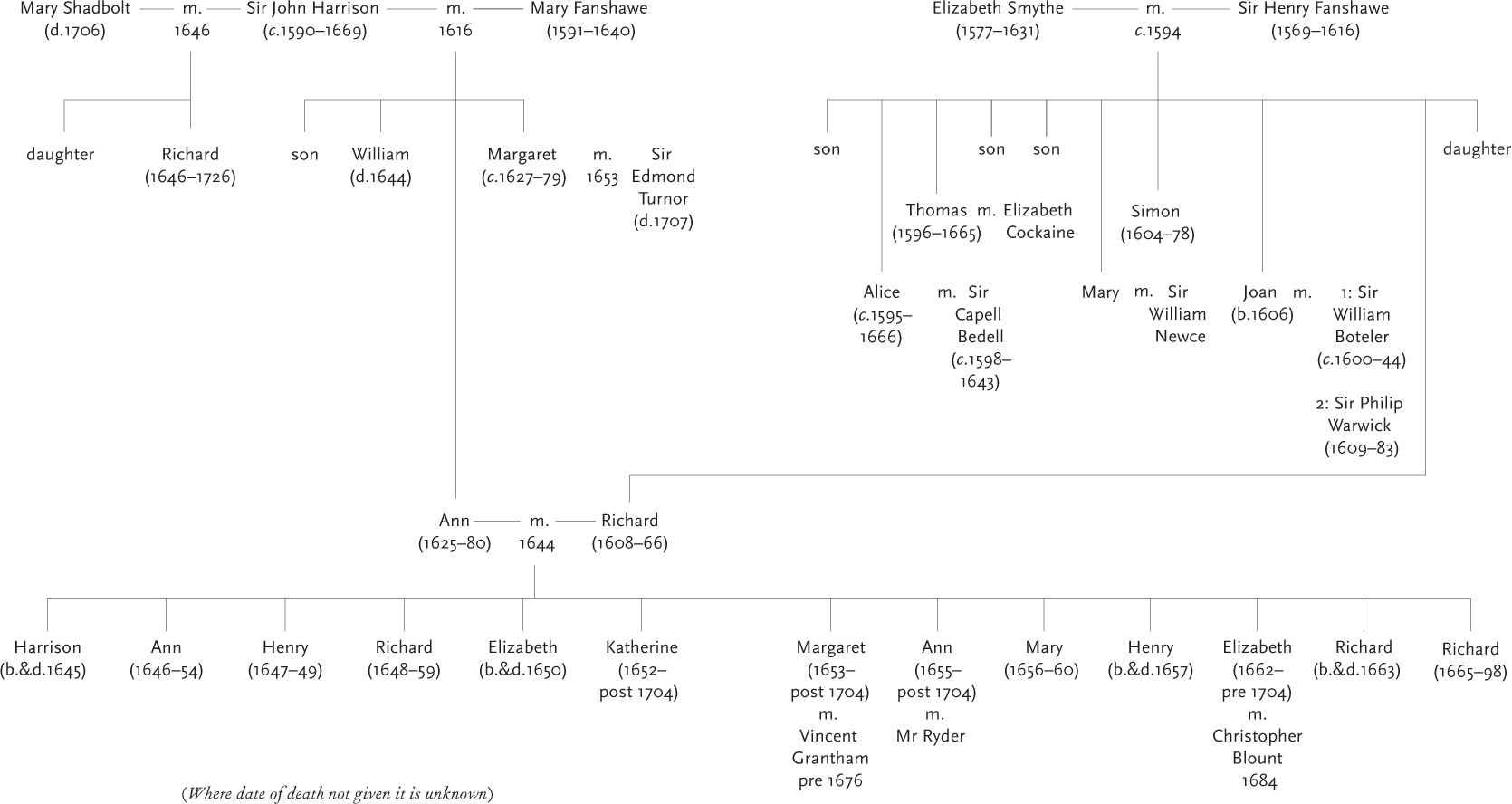

Lady Fanshawes Family Tree

Introduction

I n the seventeenth century a receipt book was not, as you might imagine, an aid to accountancy according to the OED, it didnt acquire that meaning for another century. Four hundred years ago, a receipt book was what today we would call a recipe book but containing medicinal remedies as well as culinary recipes, both referred to as receipts. It was the indispensable handbook for every woman who commanded a household, compiled by her from receipts given to her by friends and relations, her guide and manual as she travelled through life, wherever it might take her.

Ann Fanshawe, whose receipt book will serve as our guide to her life, was born in 1625, the daughter of a prosperous servant of the crown. Her father, Sir John Harrison, had arrived in London as a young man with 13 in his pocket and made a great fortune as a customs officer. He owed everything to the king. When they began, the civil wars spun the Harrisons world on its axis. A decade of dissastisfaction with Charles Is autocratic rule had turned much of the country and, significantly, a great proportion of his MPs against him. In January 1642, after the king ignominiously failed to force Parliament to charge its five leading critics of his rule with high treason, he fled London and began to gather his forces together, preparing for war.

At seventeen, taking flight from her home to join Sir John with Charles at his court-in-exile in Oxford the following winter, Ann brought with her only what she could carry on horseback: some clothes, quilted or fur-lined against the cold, and a sheaf of her mothers receipts that she had copied out as a childhood handwriting exercise, thrust into a cloak bag. Today, refugees carry their world in their mobile phone contacts, memories, plans and dreams. For Ann, the world she hoped to remember and recreate was in that slim bundle of papers.

These remedies and recipes were the core of what would become Anns large (20 by 32 cm) book, thick cream pages handsomely bound in gold-tooled brown leather and written out in sepia ink probably mixed by Ann herself from copper sulphate, oak-galls and gum. (Her book does not contain instructions for making ink, but many did.) There are remedies from society doctors and one from a London apothecary; one medical recipe comes from an advertisement, torn out of a news-sheet and stitched into the pages. Although most entries are undated, the earliest is marked 1650, when Ann was a young wife and mother aged twenty-five, and the last was added long after her death, indicating that her daughter, to whom she left the book, continued using it for many years. (What happened to it next we dont know: Anns daughter was unmarried and didnt have a daughter of her own to hand it on to.) Other surviving receipt books, like commonplace books, contain evocative extraneous material: lines of poetry, snippets from the Bible, shopping lists, pressed flowers and leaves, shaky letters of the alphabet in a childs hand, rough copies of correspondence, scrawled accounts, sketches, prayers. They are maps of their owners worlds, records of their hopes, demonstrations of wealth or poverty, culture and social ties, witnesses to joy, failure and despair.

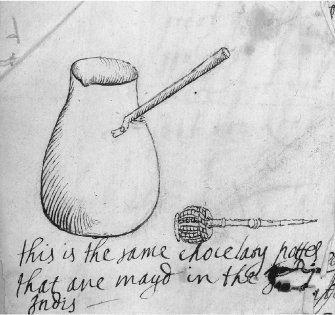

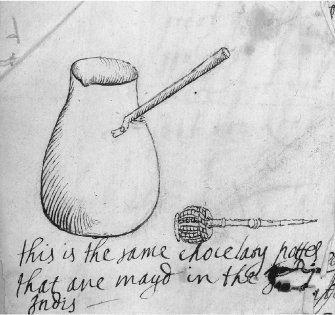

Except for chocolate from the Indies, she noted with characteristic attention to detail, the best was made in Seville.

I have concentrated on the medicinal receipts, using one to introduce each chapter. Usually placed at the front of receipt books, the remedies were at the heart of this type of book, vital for the basic survival of every family. At a time when there was only one licensed doctor at work in the entire county of Shropshire, for example, a woman of status, as Ann was, would be depended upon to dispense medicine and nursing advice not just to her own family but to the families of her dependents and neighbours of all classes. In the absence of hospitals as we know them today women attended each other in childbirth and nursed even the mortally sick in their own homes. Whatever medical knowledge they had gleaned from their mothers, friends or doctors over the years might well turn out to be the difference between life and death for themselves or their loved ones.

Anns sketch of a chocolate pot, used for making the fashionable new drink of chocolate, and its molinillo, or whisk.