2019 Paula Kay Lazrus

All rights reserved

Set in Utopia and The Sans

by Westchester Publishing Services

ISBN 978-1-4696-5339-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-53402 (ebook)

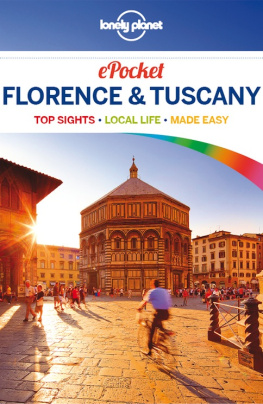

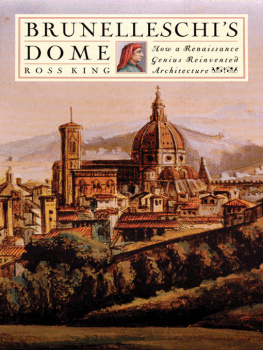

Cover illustration: Painting of the Piazza della Signoria in Florence by Bernardo Bellotto (17211780), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest (Photo by Web Gallery of Art).

Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press

116 South Boundary Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808

www.uncpress.org

Introduction

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE GAME

This game focuses on the competition to complete the final phase of construction on the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence in 1418. It was the great challenge of a generation of workers to figure out how to execute the dome designed by Nero di Fioravanti, a project that consumed the lives of many of Florences citizens and that has provided food for thought and debate for many generations of Florentines, foreign scholars, and visitors. Throughout the nearly century and a quarter during which the cathedral was being built, Florence saw a period of enormous economic growth and prosperity, and with that came a desire to thank God for those riches through the construction of churches, chapels, hospitals, public civic buildings, and plazas filled with art. Sometimes these projects were little more than ways for the wealthy to display their power and intellectual bona fides. In other cases, works of art or buildings might demonstrate to the citizenship that a leader was grateful for his good fortune and/or to promote the ideals of the day. The distinctions we make today among disciplines as diverse as engineering and mathematics, philosophy and art were less acute during the period in question, one in which the basic concepts of what should be taught and what makes for a good citizen were in flux. The early Florentine projects represent the foundations leading to a flowering of art and culture that is known as the Renaissance, a period of intellectual and creative exploration that was grounded in an appreciation for human achievements, past and present, today referred to as humanism. The game will allow you to investigate the intersection of the creative ideas, practical skills, and ideas about applying past knowledge to current problem sets and their intersection with the newly articulated ideas about the development of a good society.

The early 1400s were a moment of scholarly ferment with new ideas emerging that were developed by intellectuals looking to understand how best to develop good citizens, citizens who are crucial to the healthy functioning of a republic that requires civic participation. Florence prided itself on the fact that it was an independent republic finding its roots in its original self-governing structure as a simple municipality in the twelfth century. It was proud of the fact that as it grew and prospered it did not fall to a prince or duke (at least until the sixteenth century), but rather remained independent, governed by its citizens even as it undertook to expand its territory to include other municipalities within the surrounding territory (such as Arezzo and Pisa).

This was also a time when many manuscripts from the Roman era once thought lost to common usage were beginning to come to light through chance discoveries in monastery libraries. They were being translated from Latin, Arabic, or Greek into Italian. Some of these challenged received wisdom from the past. Others provided information about methods and ideas that had vanished with time. In fact, several crucial ancient works had only just been rediscovered and made available for study at the time our game begins. A copy of Vitruviuss De Architectura ( On Architecture ) was uncovered in 1414 in Saint Gallen, Switzerland. It contained instructions for building the kinds of monuments that people could see (some in ruins) and marvel at. How, Florentines and others of the early Renaissance wondered, could the ancients have built these amazing structures? What tools did they use? It seemed almost impossible to some that people living so long ago could have constructed the immense temples and other buildings still visible in towns and in the countryside, and yet, there they stood for all to see. Today, we look back on the monuments of the past and think much the same thing. On the other hand, the new thinking of the period encouraged people to value and exalt the skills and creativity of past individuals and try to apply it to current projects. Vitruvius not only wrote of the great ancient monuments and their proportions, decorations, and settings but provided information on the technologies used to build them. It is a key text for this game, as are the challenges facing those who wanted to see the dome completed. Those who would attempt to understand what Vitruvius was aiming for and apply it in their own work would be acting within the world of humanistic ideals.

The game is set in the period that the ideas that would become known as humanism were first being explored. Some people date the beginning of these ideas to the works of Petrarch in the 1330s. He wrote to convince people of the value of classical thinking as opposed to the then common reliance on the direction and faith of the church. This was quite contrary to the common way of thinking that did not look to the individuals contributions and worth as something developed by the individual but rather given by God. Some of the texts written roughly within the time frame of the game (early 1400s) developed ideas concerning what made Florence unique, or what made for a good citizen or a good society. They questioned earlier interpretations and ideas about how Florence was founded and what made for a strong civic society and proposed new ones. This questioning of received knowledge becomes fundamental to humanist thinking. Works like those written by Leonardo Bruni and Petrus Paulus Vergerius, which are among the texts for this game, provide some of the fundamental ideas and mindsets of Florentines at this critical moment.

Florence also had citizens whom today we might consider more practical in nature, that is, the artisans and the merchants; yet they too wrote important works. They wrote about art and about perspective (how to give the illusion of space in a painting or building), and they wrote about business and trade and foreign relations. In fact, the things that concern them in some cases still concern us today. One significant difference is that Florentines in the early 1400s valued people with very broad skill sets. A businessman might also be a musician, or an artist, or if he were not so inclined, he might use his money to support the work of such people. Those who funded projects and commissioned art and architecture and music were patrons (supporters) of those fields. The artists themselves sought out these people in order to make a living. In sum, this idea that humans can contribute to the well-being of society from its social and economic foundations to its cultural expressions without divine intervention was fundamental to the new way of thinking.