Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

Email:

Website: www.helion.co.uk

Twitter: @helionbooks

Visit our blog http://blog.helion.co.uk/

Published by Helion & Company 2013

Designed and typeset by Farr out Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Cover designed by Paul Hewitt, Battlefield Design (www.battlefield-design.co.uk)

Printed by Gutenberg Press Limited, Tarxien, Malta

Text Estate of Erwin Bartmann/Derik Hammond 2013

Photographs Estate of Erwin Bartmann 2013

Maps as individually credited

ISBN 978 1 909384 53 8

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 910294 27 7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of Helion &

Company Limited.

For details of other military history titles published by Helion & Company Limited

contact the above address, or visit our website: http://www.helion.co.uk.

We always welcome receiving book proposals from prospective authors.

Contents

List of photographs

List of maps

Acknowledgements

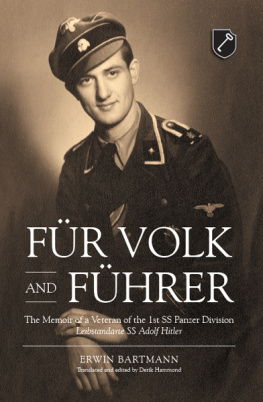

M y thanks must go to Mr. Derik Hammond of Broughty Ferry, without whom this memoir would never have been written. I first encountered him on the Forum der Wehrmacht, a meeting place on the internet for those interested in the history of the Second World War. When I discovered he lived just over an hours drive away, I invited him to visit my home in Mid Calder, near Edinburgh. After chatting with him at length about what it was like for me growing up in Berlin under Hitler, and my experiences as a Leibstandarte soldier, he suggested it might be worthwhile assembling the many episodes I had already written down in German, into a publishable memoir in English. During monthly visits lasting six hours at a time and stretching over two years, he probed every corner of my memory to reveal details hidden by the passage of time. Also, a recent minor stroke had left me unable to use a keyboard, so the task of preparing the manuscript was left entirely to him. The end result is an account that follows the major events in my early life, from the day I witnessed Horst Wessels funeral until my release from a POW camp in Scotland in 1948.

Introduction

M y name is Erwin Walter Bartmann. My parents married on 14 February 1914, a romance that produced four sons. Tragedy visited their young lives when their first born, Hubert, died of a lung infection. My brother Horst was born in the summer of 1920 and little Heinz soon followed but, at the age of just eighteen months, he too died and was buried beside Hubert, in Schlochaus Waldfriedhof. As the youngest of the four boys, I only know Heinz and Hubert through photographs and the wistful reminiscences of my mother.

We left Schlochau in 1927 and moved to Berlin where my parents rented a room from a Jewish family. Then my father, who had retired from the Post Office on medical grounds, came up with the idea of opening a fruit and vegetable business and we moved to a tiny flat in Liebig Strasse where he set up shop. Every morning with his squeaking handcart, he brought produce from the market hall on Alexanderplatz for Mother to sell from a stall at the roadside. The business failed, compelling my father to abandon his dream of self-employment. To make ends meet, he took a job in a grocers shop on Lichtenberger Strasse and, just as he had done when he had his own business, set off early each morning for the same market hall on Alexanderplatz to load up a cart with fruit and vegetables. Eventually, he saved enough money to enable us to rent a two-roomed flat at 38 Strausberger Strasse, in the Friedrichshain district and a little closer to the city centre. An iron stairway, its handrails worn thin and brown, led to our new flat, which shared a toilet in the stairwell with three other families, including a Jewish family who lived next door on the same landing. There were two girls in this family, one about my age, the other a little older. By the end of 1929 my father lost his job. To supplement our meagre family income my mother, a seamstress by profession, made blouses for well-to-do ladies and scrubbed the stairs of the apartment block to earn a reduction in rent.

I attended the local Volksschule, which lay almost directly across the street from our flat. From the outset Herr Werth, the headmaster, was my class teacher. A small man with a great love of music, he told us of his boyhood ambition of becoming a musician and encouraged us not to repeat his mistake. Always follow your dream, he advised. He was eternally cheerful and helpful to his pupils, characteristics that made it impossible for me not to hold him in high regard. During his frequent departures to attend to official duties in his office, the presence of volunteers aunts or mothers of fellow pupils, and the promise of corporal punishment for any boy who overstepped the bounds of acceptable behaviour maintained class discipline.

Hitler came to power shortly after my ninth birthday. As I grew into my teenage years I watched with admiration Hitlers personal guard, the Leibstandarte, parade the streets of Berlin. Immaculate in their black uniforms and shining helmets, their ranks marched in precise step a sight that made my boyish heart race with pride.

In the streets, in the media, the voice of the German people rang with optimism. Everyone around me was happy. A rising mood of confidence overwhelmed my world and I felt secure, valued. As a young Berliner too young to have an interest in politics what could be more honourable than aspiring to join the elite, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler? That the situation was not as idyllic as it appeared was something I had yet to learn.

This is neither a tale of the mechanisms of war nor of great strategic manoeuvres. This is my story memories from my youth and the time I served as a soldier of the Leibstandarte. The events I describe are those experienced from my own perspective as an ordinary soldier. With pride, nave pride perhaps, I took my oath to Hitler and swore, gehorsam bis in den Tod (obedience unto death).

Most of those I write about are now long dead; Kameraden upon whom my life once depended, officers who won the devotion of their men and townspeople and farmers of the lands we occupied in our fight against Bolshevism. In a very few instances I have taken the liberty of changing a name to protect the identity of an individual. The reader should also bear in mind that the dates I give for particular episodes in my life at the Ostfront, unless they relate to some personally significant event like a birthday or anniversary, or a highpoint in the calendar, are either approximate or taken from reliable published works such as Rudolf Lehmanns series The Leibstandarte. An ordinary soldier of the Leibstandarte was not permitted keep a diary that an enemy might use to gain useful intelligence. Furthermore, keeping a record might well have brought accusations of spying.

At the age of 88 years, I am, in the words of the song of our Pionierkorps, zur Himmelstr (at heavens door). I have nothing to gain by misrepresenting the truth. My aim is simple: to give the reader an insight into the life of a boy who grew up to become a soldier in Hitlers elite division, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler.

A Diary of Indoctrination

Saturday 1 March 1930

A chill mist saturated the air over Berlin but even the worst weather could not dampen my fathers passion for walking. Are we going to the park

Next page