Also by Nick Bunker

An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America

Making Haste from Babylon: The Mayflower Pilgrims and Their World

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by Nick Bunker

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

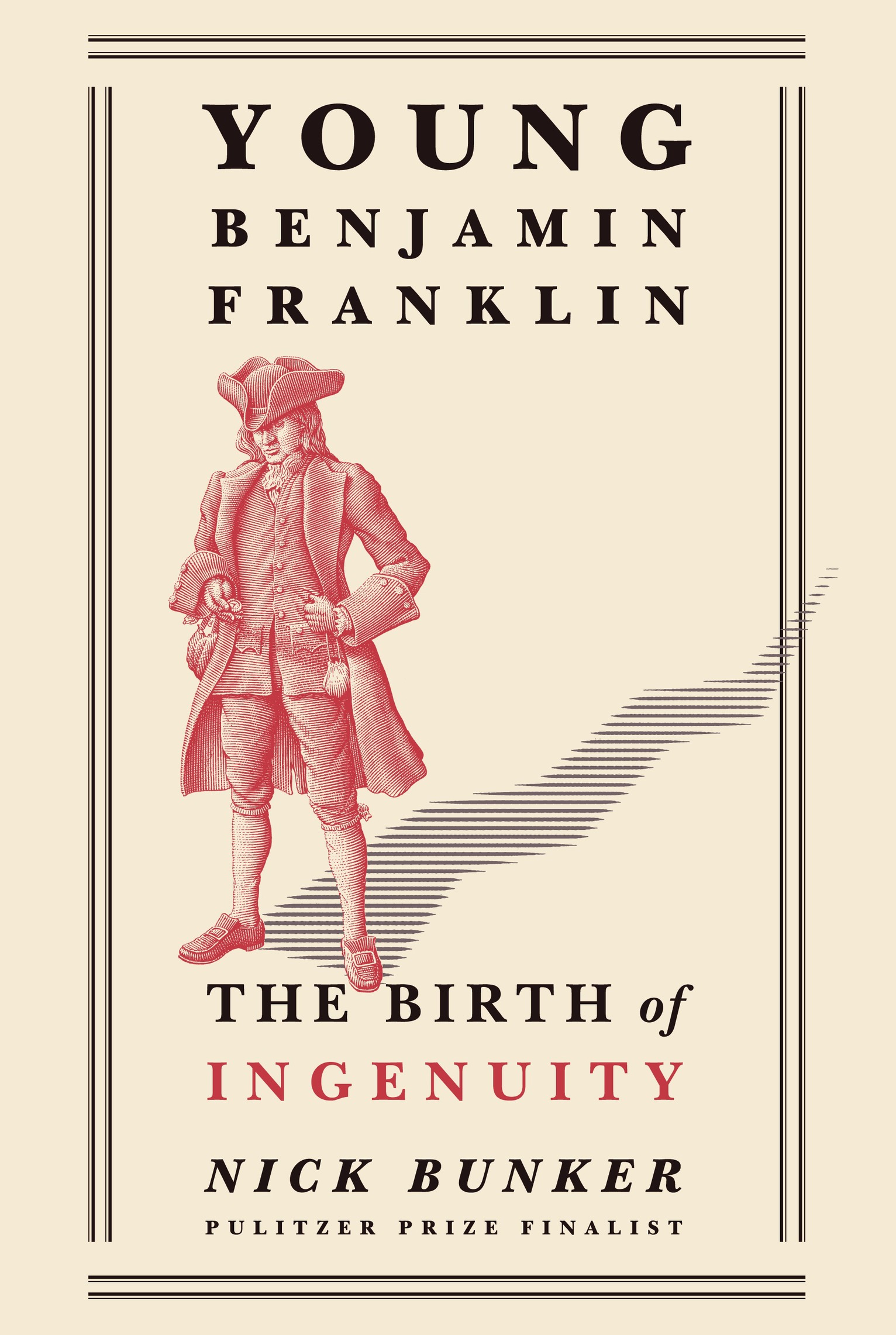

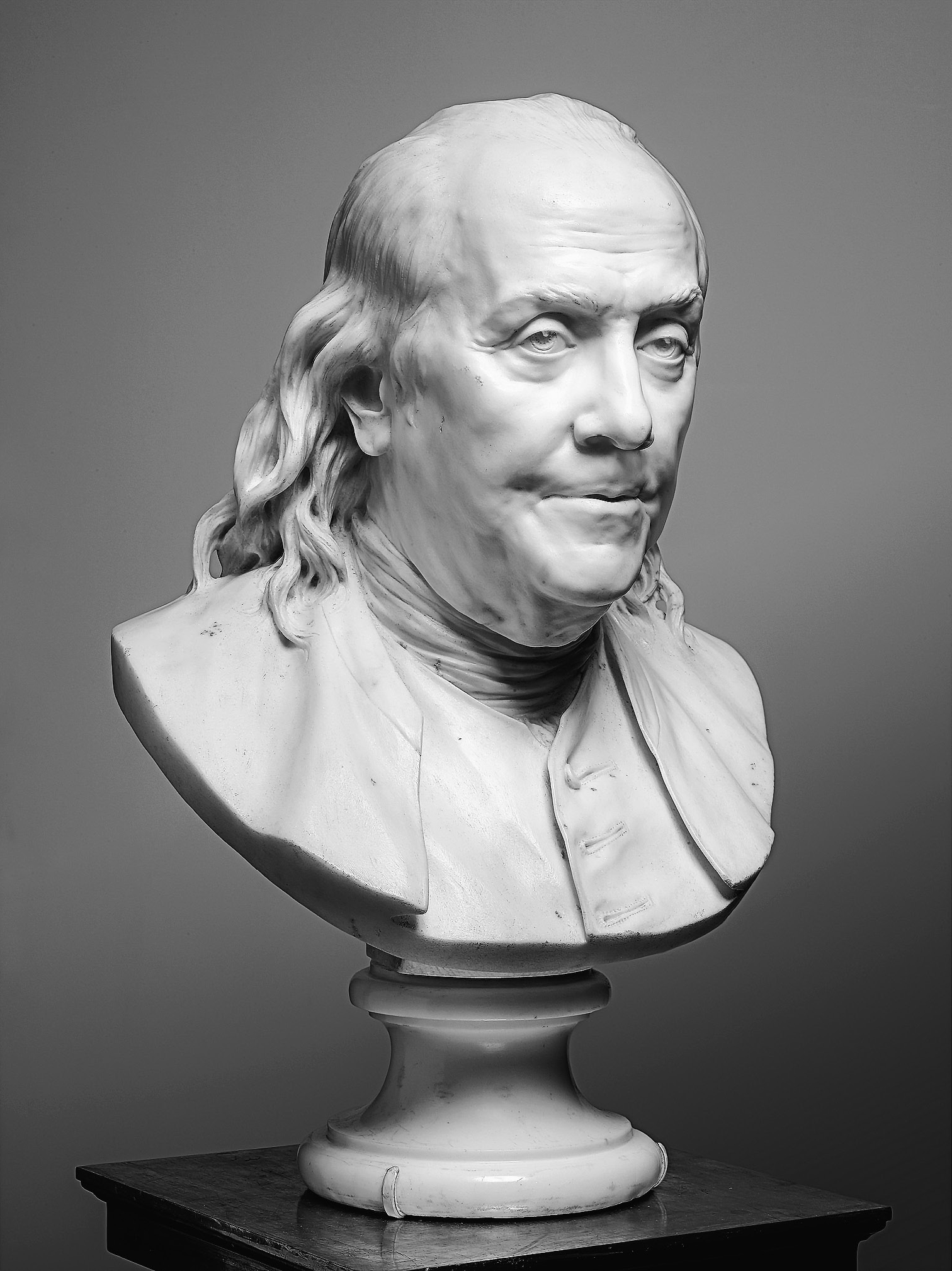

Jean-Antoine Houdons marble portrait bust of Benjamin Franklin at the age of seventy-two, made in Paris in 177879. Philadelphia Museum of Art: see .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bunker, Nick, author.

Title: Young Benjamin Franklin : the birth of ingenuity / by Nick Bunker.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2018. | A Borzoi Book.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017057711 | ISBN 9781101874417 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101874424 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Franklin, Benjamin, 17061790Childhood and youth. |

StatesmenUnited StatesBiography.

Classification; LCC E302.6.F8 B8833 2018 | DDC 973.3092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017057711

Ebook ISBN9781101874424

Cover illustration by Michael Halbert

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v5.3.2

ep

In Memory of Henry Chapman Mercer (18561930)

Founder of the Mercer Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

An ingenious American

Contents

Prologue

T HE E NIGMATIC S EER

Behold, all alive, one of the ancestors of modern America!

A UGUSTE R ODIN, 1910, ON THE BUST OF F RANKLIN BY J EAN- A NTOINE H OUDON

Before we share the story of his origins and early years, we begin with a glance at the man as he was late in life: Benjamin Franklin, the affable sage, in the Paris where he played the role of diplomat. With his long hair, his paunch, and his spectacles, he delighted his hosts in France with a manner that conveyed serenity as well as charm. Some of us can do gravitas, and some of us can do joie de vivre, but the Franklin of 1780 could do both. It was a rare combination, and all the more exceptional because it seemed to come so easily.

As Americas envoy to the court of Versailles, Franklin could hush the chatter in a salon merely by pausing for a long while before he replied to a question. An oracle at peace with himself, or so it seemed, Franklin was always friendly and polite but also rather distant and reserved. Here was a sage who could be funny when he chose, but somehow never lose his aura of gentility.

Partly the secret lay in his build, stricken though he was by arthritis and the gout. In his prime, Franklin had been broad-shouldered and muscular, an inch or two under six feet tall. Even now at seventy, leaning on a cane, he struck one French observer as a very big man with an excellent figure. Although Franklin would lounge for hours over breakfast, reading the news from the war with the British, the long legs that stretched out across the floor were still firm and shapely: a very handsome leg, one visitor recalled.

Besides the long pauses, which made the big American seem so august and sublime, Franklin had another way to be inscrutable. Unlike most public men of advancing years, he rarely bored his listeners with tales of past achievements, and least of all did he speak about his boyhood and his youth. This was true of his correspondence as well as his conversation. When we turn to his letters, surviving in the thousands, we meet a Franklin who took the utmost pride in his grammar, his spelling, and the rhythm of his prose, but we will mostly search in vain for intimate details of his early years. Instead they show us a practical, up-to-date Franklin, for whom historyincluding his ownalways seemed to matter far less than the future.

And so besides the dignity and the gravitas, Franklin also had a touch of mystery. By saying so little about his past, he maintained his aura of reserve, and he did it so well that it has endured until the present day. After a lifetimes study of the man, scholars sometimes come away feeling that Franklin will always slip through our fingers. He kept a kind of inner core of himself intact and unapproachable, wrote Edmund Morgan, the historian from Yale, in one of the finest books about him. In Franklins own era, those who tried to grapple with the sage often found him even more elusive. Whether they loved or hated Dr. Franklin, they could simply never pin him down.

Where had he come from? That they knewfirst Boston, and then Philadelphiabut it was hardly much to go on. What were his origins? Who were his family? How had he become the genius he was? Today when we look for answers to these questions we simply open his autobiography, written in fits and starts over the space of twenty years. There we find a very different Franklin, a man who loved to delve into his roots; but in his lifetime he chose to keep the book from the public eye. Not until 1791, the year after his death, did the first edition of his memoirs appear in print. Even then it was only a French translation and it was incomplete.

As far as the outside world was concerned, his career had begun with a flash and a bang in 1751, whenat the age of forty-fivehe published the first edition of his scientific papers, Experiments and Observations on Electricity, with his startling theory that electricity and lightning were identical. After that Franklin was rarely out of the news, as he played his many parts as scientist, politician, ambassador, and rebel. His earlier life was something else entirely: provincial, obscure, and all but impossible to reach.

In the Philadelphia of the Revolution, there were aging citizens who remembered Franklin the printer, bent over the proofs of The Pennsylvania Gazette, but that was a very long time ago and the details were hard to recover. Three decades had gone by since he ceased to be the papers editor. Although everyone knew Franklin as the author of The Way to Wealth, with its maxims and its jokes culled from his annual, Poor Richards Almanack, even that was something whose origins were lost from view. In its heyday in the 1740s, the almanac had a circulation of ten thousand, but it was a product people kept for a few years and then discarded: how could they know that one day the author would be famous? As for his early journalism, written when he was a teenager in Boston, it had been forgotten long ago. Bylines had yet to be invented, and so his youthful columns disappeared into the archives, dusty and anonymous, to be rediscovered only in the nineteenth century.

With his memoirs still hidden away so discreetly, Franklins public image was very different from the picture we now have of him. For us he will always be the teenage runaway made good, a whimsical fellow with his gadgets and his jokes. In his lifetime, when they encountered the elderly Franklin what most people saw was a mountain of a man, whose sense of humor took a distant second place to his weighty achievements in science and public affairs. It was as if they had beheld another Moses: a prophet from Sinai, bearing his tablets of stone, wrapped in a cloud that concealed the sources of his energy.