Introduction

I had never planned a crime before. I usually arrive after, or during, the action.

Speed and surprise would be the most important elements: Strike swiftly, give witnesses no time to react. Dont seek approval from the people in chargeask bureaucrats for permission to do anything out of the ordinary and they either say no or launch meetings to consider the question until long past your deadline.

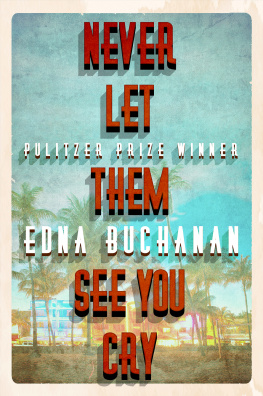

On a leave of absence from The Miami Herald to write two books, I had begun to teach a crime-reporting class at Florida International University. At first I was unenthusiastic about teaching. An accidental journalist who had never studied the subject or attended college, my only qualifications were a 1986 Pulitzer Prize, a book called The Corpse Had a Familiar Face, published in 1987 and now in use at some journalism schools, and thousands of stories on Miamis police beat. But the offer to teach was one I could not refuse. Journalism had been very good to me, and pay-back time had arrived.

The class took only one night a weekno problem, that would leave ample time to write my books.

Wrong.

I became hooked on teaching. The term was exciting, the students terrific. We dialogued with experts from the police beat and took a field trip to the county morgue. We posed with the chalk outline of a corpse, surrounded by police crime-scene tape, as Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Brian Smith shot our class picture.

And I plotted a perfect crime.

No guns, I decided. It was unlikely that any of my eager students would come to class armed, but this was Miami, a city like no other, unpredictable and stranger than fiction.

Ann and D.P. Hughes, the friends recruited to be the perpetrators in this piece of street theater, were uneasy. I dont want to have to hurt anybody, D.P. muttered. The tough and savvy chief of operations at the Broward County Medical Examiners Office, Daniel P. Hughes is also a lawyer and a certified police officer. Ann is his wife. Should you fall grievously ill or injured and spot her sweet face at your bedside, you are in serious trouble. In her soft and soothing southern accent she will talk you, or your next of kin, right out of your vital components. At the very least, she wants your eyes, skin and bones. Your heart, liver, lungs and kidneys would be ideal. Arranging the harvest of human organs and tissues is her job, for the University of Miami and Jackson Memorial Hospital. A woman who smiles freely and laughs often, Ann is dead serious about her work. She is as dedicated to tracking down the right parts for people who need them as D.P. is to investigating how and why some stranger died.

While we conspired, I pointed out to my uneasy friends that these college seniors were not aspiring cops or Marines but would-be journalists: At moments of high excitement they take notes, not action. But I promised to shout Nobody move! Stay in your seats, the moment D.P. burst through the classroom door. Dont worry, I insisted. It will all happen so fast, they wont know what went down. Theyll freeze in their seats.

Wrong again.

Midway through my lecture on good cops-bad cops, Ann made her entrance as planned, through a door behind me. She frantically scanned the students faces. Where is my son? Isnt this the journalism class? Youve got to help me. Theres been a terrible accident, I have to find my son and take him home.

She was good. Very good. Tearfully, she tugged at my arm, skillfully maneuvering me around, drawing me back toward the door she had entered. Remember, this is a woman who can talk you out of your vital organs. She was so convincing that even I, the architect of the scheme, was suckered in.

I missed my cue.

D.P. burst through another door, snatched my black leather handbag off the desk and took off running. I never saw him. By the time I turned around, he was out the door, two students in hot pursuit Scuffling sounds made me spin back toward Ann. She too had fledor tried to. Before she could escape, a petite woman student had seized her belt from behind and was now scaling her back like a Sherpa ascending Mt Everest.

Outside the classroom, D.P. reached for the police badge tucked in his belt. His pursuers momentarily fell back. Miamians, they assumed he was drawing a firearm. The rest of the class surged forward, a human tidal wave scattering furniture in its wake.

Finally I remembered my lines.

Freeze! Nobody move! I flung my arm at the wall clock. Youre on deadline. You have fifteen minutes. Write what just happened. Give me a lead, quotes and descriptions, height, weight, clothing.

Thirty-four astonished young men and women froze in disbelief. Nervous, adrenaline-charged laughter rippled through the room. Several students stared accusingly. They had been had. A burly young man, big as a linebacker, was too shaken to grasp a pencil.

The lesson, of course, was the fallacy of eyewitness identification, so beloved by juries, so consistently inaccurate.

The written accounts, from these alert young observers who saw everything under excellent conditions, were widely diver-gent.

Ann is lanky and fashion-model tall, with shoulder-length dark hair. She wore a green print jumpsuit. One earnest would-be reporter described her as a petite blonde in a mini-skirt. D.P.s height estimates ranged from five feet six inches to six feet two inches. Anns attire was described as a leopard print, D.P.s as a dark, FBI-style ensemble. Neither was correct.

An excellent lesson. Hopefully they will never forget it when encountering eyewitnesses. The experience was revealing. Two of the three students quick and courageous enough to chase the criminals were young women. That one of them put it together fast enough to pursue Ann without hesitation astonished me.

The students reactions demonstrated how violence and crime have changed people since I first began to cover the police beat two decades ago. We react faster and more aggressively. Perhaps that is why television shows on unsolved mysteries and wanted fugitives are so successful. Viewers jam telephone lines calling in tips, turning in their neighbors. We are all fed up with crimes unsolved and missing children never found.

Crime fighting has become a participatory sport.

A few years ago who would even have envisioned a journalism course specializing in crime reporting? Teaching it remains a fond memory, but I will never do it again. I became too fond of my students to replace them with a room full of strangers. My time is better spent reporting and writing.

The term ended, and before saying good-bye, I made them promise to always observe the journalists three most important rules: