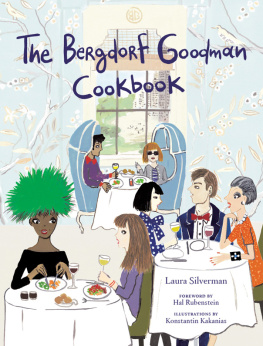

SCATTER MY ASHES AT

BERGDORF GOODMAN

Sara James Mnookin

Foreword by

Holly Brubach

CONTENTS

I want my ashes scattered over Bergdorfs.

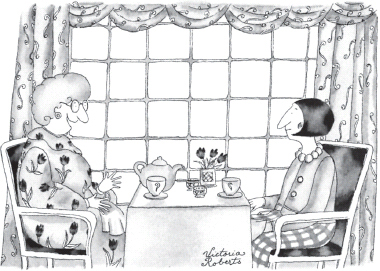

Victoria Robertss infamous cartoon first appeared in The New Yorker in 1990.

F rom an early age, I loved stores and the theater of shopping. I even had fantasies of being locked in a department store after closing, having the place to myself and roaming the floors, spending the night. I would dine in Housewares and sleep in Linens, in pajamas selected from the racks in Lingerie. Unquestionably, there were things I coveted, but my fascination with stores and shopping was not motivated by the urge to acquire so much as by the pleasure of discovery.

Media in those daysin the Dark Ages, before the dawn of the Internetconsisted of newspapers, magazines, and television, but looking back, I see that stores were media too: from the grands magasins of Paris, commemorated in luscious detail in mile Zolas Au bonheur des dames, to the Main Street importers of dry goods in small towns strung like beads along the railway lines that crossed the map of America. A store was an emporium, a place where people came not only to buy but also to browse, a de facto museum filled with beautiful and useful artifacts, displayed in their own time, available for sale. Before everyone had been everywhere and seen it all, stores brought their customers the world.

After college I moved to New York City and took a part-time job, working afternoons at a fashion magazine, and Bergdorf Goodman was along the route I walked to my office. Some days I lingered in front of the windows; others, I cut through the first floor, entering in Cosmetics and exiting through Van Cleef & Arpels. The merchandise was an object lesson in connoisseurship. The detour added no more than five or ten minutes to my walk, and I came to regard it as a quick adventure, a brief escape from the routine of my still unformed, sparsely furnished life.

The oasis of calm, with the bustle of Fifth Avenue beyond the doors. The impeccably polite demeanor of the staff. The quiet presence of the proprietors family living upstairs, over the store, in a penthouse apartment under the mansard roof. The silver box and lilac bag in which some newfound treasure made the trip home. If Paris was for me the acme of civilization, Bergdorfits architecture reminiscent of a Gilded Age mansion, its plush salons, its sublime refinementhad grafted Paris onto New York.

That proprietary blend of Avenue Montaigne chic and Park Avenue style would qualify today as a case study in corporate branding, but when I made the stores acquaintance back in the late seventies, nobody but a few farsighted business-school professors thought in those terms. Still, stores, like people, had personalities. Bonwit Teller was your dowager aunt, dignified and straight-backed, dropping the name of a rock band or the latest film just to let you know that she kept up. Bloomingdales, brash and kinetic, was a working girl who partied hard. Henri Bendel was an urban original, witty and artistic. And Bergdorf Goodman was a woman at home in the world, glamorous, discreet, with an elegance that informed her every gesture.

I liked them all, but it was in Bergdorfs company that I wanted to pass the coming years. I became a customer, and Bergdorf took me on, treating me with all the deference and kindness of a friend. I bought my clothes there, and for eleven years they were fitted by Elvira Nasta, a gifted seamstress who worked in the alterations department.

Elvira had the sartorial equivalent of a piano tuners perfect pitch and a vast repertoire of tricks to make a garmentany garmentlook as if it had been designed and made for me expressly. She saw me on my fat days and on my thin days. She knew the ways in which my figure deviated from the standard sizes, and she passed no judgments. We talked a lot, mostly about food, men, and getting older, and we laughed often. We spent countless hours together in a fitting room the size of a boudoir: me, concentrating on standing tall, balanced on the high heels I would wear with the dress in question; Elvira with her pincushion, moving in slow circles around me, calibrating the hem, scrutinizing the contour of every seam.

When after twenty-six years she retired, I was bereft, although I knew better than to think that Elvira would miss me as much as I would miss her. As a kind of farewell exercise, I interviewed her for a column I wrote in the New York Times Magazine. She told me she was enjoying retirement, but the satisfaction her work had brought her was gone. When a garment was all finished and Id see the woman dressed, it gave me great pride, she said. Leaving the house for a meeting, a dinner, a fancy-dress ball, I had the feeling that Elviras good wishes went with me, sewn into the outfit I was wearing, like a fairy godmothers benediction.

In these days of search engines, one-click orders, and free shipping, its difficult to talk about how much Bergdorf Goodman has meant in the lives of its customersin the life of this customer in particularwithout sounding hyperbolic and sentimental. As I write, a voice in the back of my mind keeps advising me to discount these recollections. This is, after all, shopping were talking about. Listen, I tell myself, it was just a store.

But it wasnt. And it isnt.

Holly Brubach

E dwin Goodman could never have fathomed what lay ahead when he left Lockport, New York, borrowed some money from his uncles, and purchased a stake in Herman Bergdorfs Manhattan atelier. The year was 1901, and Bergdorf, a gregarious Alsatian immigrant and gifted tailor who lacked ambition, spent much of his time at Brubackers wine saloon, leaving his clients to wait.

Goodman, at just twenty-five, was handsome and serious, with a drive and dedication beyond his years. He seemed, at first, to be the ideal partner for Bergdorf. The ladies suit had just come into fashion, and from its modest perch at Fifth Avenue and Nineteenth Street, the newly formed Bergdorf Goodman was turning out some of the citys finest. As orders rolled in, Goodman urged his elder partner to move the operation uptown, to a bustling stretch of Fifth Avenue known as Ladies Mile.

Shortly thereafter, while Goodman was honeymooning in Europe, Bergdorf did move the storebut not to the swanky address his young partner had been envisioning. Instead of opening directly on Fifth, next to prestigious dry goods emporiums and department stores such as B. Altman, Lord & Taylor, and Best & Co., Bergdorf leased a sleepy spot at 32 West Thirty-Second Street. A man whose lone indulgence was a bottleor threeof Alsatian wine didnt see the point of spending on Fifth Avenue frontage.

The out-of-the-way location irked Goodman from the moment he returned to New York. He bought out his partner, and Bergdorf headed off promptly thereafter to Paris to retire happily a free man.

In 1914, Goodman upgraded to a five-story building at 616 Fifth Avenue, constructed to his specifications. Though he initially sublet some of the square footage to help cover his costs, he still had far more space than the cramped quarters on Thirty-Second Street. However, once he hired Ethel Frankau, a stylish schoolteacher-turned-dressmaker, his client list quickly grew to fill up every floor.

Goodman had never been satisfied to follow trends in womens couture. He toyed with convention, adding box pleats to hobble skirts, encouraging clients to discard the Victorian jabots around their necks and constricting corsets about their waists, cutting furs to the body so they were no longer bulky and unflattering, and, most important, introducing quality ready-to-wear in the twenties.