Contents

Guide

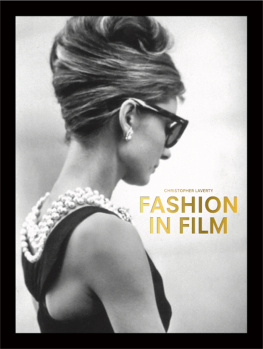

FASHION IN FILM

For Mum & Dad

Published in Great Britain by

Laurence King Student & Professional

An imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

First edition published in 2013; this edition published in 2021

Text 2021, 2016 Christopher Laverty

The moral right of Christopher Laverty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

TPB ISBN 978-1-78627-709-1

Ebook ISBN 978-1-52942-0-944

Quercus Editions Ltd hereby exclude all liability to the extent permitted by law for any errors or omissions in this book and for any loss, damage or expense (whether direct or indirect) suffered by a third party relying on any information contained in this book.

Designed by Sarah Schrauwen

CHRISTOPHER LAVERTY

FASHION

IN FILM

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

F ashion in film does it even exist? Some might argue no, that the very phrase is redundant. After all, everything we see worn on screen is, by definition, costume. Yet that is too simplistic a concept. If costume only becomes fashion away from the screen, what happens when we return? When we look at the meaning and impact of costume on the world of fashion alongside its intentional role of bringing characters to life? Then we have distance, the ability to combine fashion and costume as a cultural fixture.

This book concentrates solely on the work of fashion designers that have created clothing for film, or in some cases vice versa those who have worked in costume and then become fashion designers but the overall rationale is that the designer must have functioned in both industries during their career. This is to aid scope. It became apparent during my initial research that writing an entire book about how fashion has been affected by clothes on screen is a different publication entirely. I wanted to keep this title distinct and focused.

Narrowing down which designers and which films to focus on was, to be a honest, a nightmare so many to include and only a limited amount of space. How to choose? For starters, a featured designer, or house, must have designed specifically for the film being analyzed. I have considered shopped garments in each designers individual profile, but ultimately I wanted clothing by fashion designers that is intentionally created as costume. This precludes certain designers that you might expect to see, such as Comme des Garons, whom costume designer Aggie Gerard Rogers used for Beetlejuice (1988), or Zegna, who provided off-the-rack suits for George Clooney in The American (2010). The same goes for certain costumiers, like Bob Mackie, who designed for screen several times (Pennies From Heaven, 1981; Staying Alive, 1983) but is primarily known for stage wear. Even Orry-Kelly and William Travilla have been omitted, principally because they are costume designers who, bar a newswire column for Kelly and scattered collections for Travilla (including one for Grattan), influenced fashion rather than existed within the industry. For many the most surprising omission will be Edith Head. Head is certainly mentioned, particularly in regards to the Givenchy little black dress for Breakfast at Tiffanys (1961), but again, apart from some tie-in collections, she was a fashion tastemaker not a designer. Even with these strict criteria to narrow the field, there just was not space to include everyone: Norma Kamali, for example, who designed gowns for the Emerald City portion of The Wiz (1978).

Other aspects of the fascinating world of fashion and film crossover include collaborations such as the unusual teaming of Muppets creator Jim Henson and fantasy illustrator Brian Froud for The Dark Crystal (1983). They produced a line of clothing based on costumes seen in the film that was sold through Libertys of London. A similar idea was employed by Disney for Oz the Great and Powerful (2013), when footwear designer Steve Madden, among others, produced over 400 accessories inspired by the movie for the Home Shopping Network. Also several high-profile costume designers worked with Prada on their Iconoclasts installations in 2015. But, however interesting these projects are, unless a major couture designer or their house was involved, and the garments were created specifically for cinema, they did not meet my mandate for this book.

Certain fashion designers were not included because the clothing they provided for a film was not deliberately designed or intended for it. Elie Saab is someone I wanted to feature, but as yet he has not created specifically for movies. His garments have been used by costumiers Kurt Swanson and Bart Mueller for Stoker (2013), for example but interpreted independently of a collaboration. The film Prt--Porter (1994) is crammed full of fashion designers and their clothing, and I could have mentioned it in every other chapter, but it is a satirical piece, not focused on clothing as much as the industry. There would have been scant analysis to make.

This Elie Saab dress, worn by Nicole Kidmans character Evie in Stoker, was chosen for the film by costumiers Bart Mueller and Kurt Swanson. Sketch by Bart Mueller

With each profile I have attempted to channel the same investigative approach I employ with my website Clothes on Film. In general, I have discussed the career of the designer in question, their background, approach, and evolution, and then examined three or four of their films in detail. I am not looking only at the clothes themselves, but exploring what they mean in the context of the story being told. I also look at the garments use as a potential marketing tool, their reverberations if any in the fashion world, and their legacy on both catwalk and screen. Occasionally, as in the case of Rodarte, for instance, I will break down only one film (i.e., Black Swan, 2010), because at the time of writing that is the designers only contribution to cinema. So why include Rodarte if they have only designed for the one movie? Because the story behind their involvement is too sensational to ignore. So exceptions have been made. You might also question why certain well-known titles have been left out or skipped over in profiles where you might be expecting to read more. While I wanted to make sure the essentials were included classics like The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Barbarella (1968) I wanted to focus on content that has never been published before, and to take the opportunity to correct details that have been incorrectly reported time and time again, such as Agns Bs contribution for John Travolta in Pulp Fiction (1994). But you can read all about that in the following pages. Dont let me keep you.