Chetwode - Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia

Here you can read online Chetwode - Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Andalusia (Spain);Spain;Andalusia, year: 2012, publisher: Eland Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia

- Author:

- Publisher:Eland Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- City:Andalusia (Spain);Spain;Andalusia

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Amber LEstrange

to whom I owe an eternal debt

M Y THANKS ARE due first and foremost to the Duke of Wellington for providing me with my companion, the other middle-aged lady; then to Bill and Annie Davis for a thousand kindnesses and above all for selecting such an exciting district for us to explore; to Eudo and Rosemary Tonsen-Rye for invaluable help and advice and to their lovely daughter Rohaise for photographing the two middle-aged ladies together; to Don Antonio Navarrete, Mayor of Quesada, for permission to publish his poem on page 82 and to Gamel Woolsey for her superb translation of it; to Mr Mervyn Scott for much patient instruction in the mechanics of photography; to my husband John Betjeman and my friend Patsy Ward for pestering me relentlessly to overcome my natural sloth and edit my diaries to produce this book; to another old and loyal friend, Karen Lancaster, for tireless work on the typescript and proofs; and last of all to the Reverend Mother Abbess and the community at Goodings Convent for providing the perfect atmosphere in which to write.

In quoting the spoken word I have followed the colloquial custom in Andalusia of clipping the final consonants.

GOODINGS

FEAST OF ST MARK 1963

I T WAS THE horse that brought me to Spain. For years enthusiastic friends had tried in vain to make me go there. I pointed out that two countries, Italy and India, were enough for ten lifetimes. How, in middle age, could I be expected to mug up the history, language and architecture of a country about which I knew next to nothing? I had not even read a line of Don Quixote. I knew Italian fairly well and if I now tried to learn Spanish I should inevitably confuse the two and end by speaking neither. I dug in my toes and obstinately refused to be lured to the peninsula by ardent hispanophiles.

Then, in a Sunday paper, I read about conducted riding tours in Andalusia. My resistance suddenly broke down and I booked to go in late October.

St Thomas says you cannot love a horse because it cannot love you back. This statement proved a serious obstacle to my entering the Holy Roman Church in 1948. Then Evelyn Waugh pointed out that St Thomas was an Italian accustomed to seeing his fathers old chargers sent along to the local salami factory in Aquino. Had he been an English theologian he would never have written like that: his fathers chargers would have been pensioned off in the park. Now I was going to a Latin country where old horses ended their lives in the bull-ring. Could I stand such an attitude to animals? I who had always been full of the traditional English sentimentality towards them? This racial antipathy was well illustrated some years ago when I brought my daughters pony into the kitchen and kissed it in front of Gina, our Calabrian maid: In Italia bacciamo uomini! (In Italy we kiss men) she had said in utter scorn.

* * *

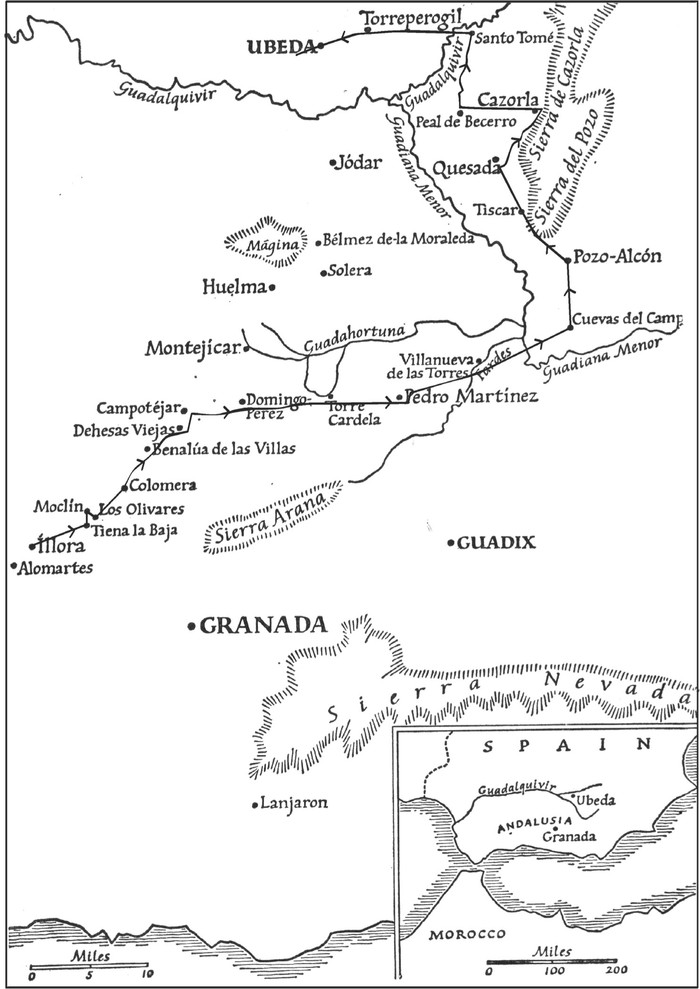

When I first arrived at Alora, the starting-point of the conducted tour, and saw the wiry little horses of the sierras, I got rather a shock. Standing between fourteen and fifteen hands high they were so much narrower than our own mountain and moorland breeds, and their conformation was decidedly odd: they had ewe necks, cow hocks and unusually straight pasterns. Nevertheless they turned out to be extremely fit, and were surprisingly good rides. They walked out well, never stumbled down the stoniest mountain paths, and had armchair canters. The soles of their feet must have been an inch thick as they never bruised them on the roughest going nor went lame from any other cause. Their narrowness would have been tiring on long rides but the Andalusian saddles provided the width which the animals lacked. They were high fore and aft, had soft sheepskin seats and were almost impossible to fall out of. Beautifully embroidered leather alforjas (saddle-bags) were hung over the cantles at the back and it was astounding what a lot one could cram into them.

The feeding of horses in southern Spain is extremely interesting because it is so different from our own. They get neither oats nor hay but paja y cebada, which is chopped barley straw chaff and barley corn fed dry. According to Richard Ford grow lucerne. The animals are also taken out to graze when work and time allow, usually along streams or irrigation canals where there is always a bit of grass, or up on the mountains where there are several plants which are eaten with great relish. When grazing they are either hobbled or put in charge of a boy. Morning and evening they are led out to water at the fuente (a trough sometimes fed by a spring, sometimes by piped supply) and when on a journey they are encouraged to drink at every stream they ford.

In England I would despise a conducted riding tour because English is my language and I am a one-inch map maniac and a lot of my delight lies in working out routes on my maps beforehand and in poring over them afterwards. But going to Spain for the first time with next to no Spanish and very poor maps, I decided that the best preparation for a solo ride (my avowed ambition) was to go on a preliminary one with people who knew the ropes: thus I hoped to learn about Spanish blacksmiths, feeding methods, inns, and cross-country navigation. I would also mug up a stable vocabulary.

I chose one of the cheap tours run by Antonio Llomelini Tabarca which was wonderful value for money, costing only 28 for a fortnight, full board and lodging of horse and rider included. Antonio is a young Sevillian whose chief delight has been to explore the sierras of his native Andalusia on a horse and now he has made a business of it and established an excellent riding centre in the hills at Alora, 12 miles inland from Torremolinos.

Antonios enthusiasm, seriousness of purpose and delightful manners do not answer to the description given of his countrymen 120 years ago by George Borrow: The higher class of Andalusians are probably upon the whole the most vain and foolish of human beings with a taste for nothing but sensual amusements, foppery in dress, and ribald discourse.

Discourse in any case was limited by ignorance of one anothers languages. On the first evening at dinner (excellent gazpacho followed by a very good curry, his cook having spent two years with an Indian family) I attempted to talk about foxhunting. Antonio made, or rather I thought that he made, the astonishing remark that in this part of Spain vixen were milked and their milk was made into cheese. What he actually said was that poisoned cheese was put out on the hills to kill foxes. I tried to warn him against indulging in such practices when he went to work in the Cottesmore Hunt Kennels where he had arranged to go during the winter in order to learn English. Do foxes really eat cheese?

Antonio had a little rough-haired terrier on short legs, the shape of a small corgi, of which he was as fond as the most ardent English dog-lover. It always slept on his bed and was very friendly with his guests. One night I went to evening devotions in the big church across the plaza. I arrived late and fell flat across the corner of a confessional, which set a whole pew of children off into a fit of giggles. Then Chico came in, singled me out as his masters friend and came and lay down at my feet. The Blessed Sacrament was exposed and instead of letting a sleeping dog lie quite innocently in the Divine Presence I got up and carried him out. On returning to my place I again fell flat over the confessional. I soon learned that it was the usual thing for dogs to wander in and out of church in Spain and that nobody minded. Many priests have dogs who regularly hear Mass sitting motionless in an aisle with apparent devotion.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia»

Look at similar books to Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Two Middle-Aged Ladies in Andalucia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.