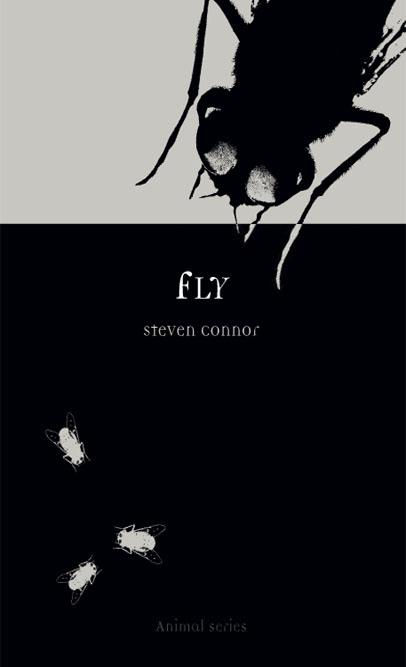

Fly Steven Connor |

|

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2006

Copyright Steven Connor 2006

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Singapore by CS Graphics

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Connor, Steven, 1955

Fly. (Animal)

1. Flies 2. Human ecology - History

I.Title

595.77

eISBN: 9781861894915

Contents

Fly Familiar

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?

William Blake, The Fly

More than the rat, the cat, the dog or the horse, the fly is our familiar. Flies accompany human beings wherever they go, and have probably done so since the first development and spread of animal husbandry among early humans. Flies are, as one of their rare celebrants has written, the constant, immemorial witnesses to the human comedy. Flies were indeed literally thought to be the familiars of witches. But flies are familiar in another sense. For what we might call the Gestalt or footprint of the fly extends far beyond its most familiar forms, such as the house fly. About one tenth of all the species known to science are flies. Not only this, many creatures that are not flies at all have nevertheless been given the name: dragonflies, butterflies and fireflies; even the flea has a name that factitiously suggests an association with the fly. The spellings flee, flea and flie were largely interchangeable in the volatile orthography of pre-eighteenth-century English. The word fly is used to signify any kind of small flying creature, of indeterminate form. Flies are so familiar that we allow them to multiply, in kind as well as number, under our noses.

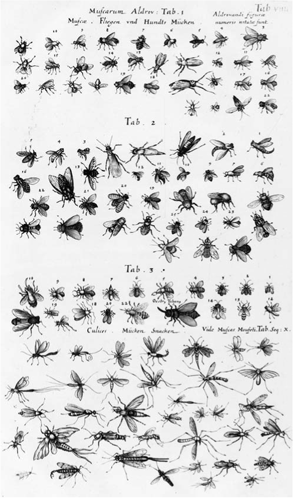

Flies are defined biologically as insects of the order Diptera (Greek, two-winged). Diptera are distinguished from other flying insects, such as dragonflies and butterflies, by having only one pair of wings. Where other flying insects have a second pair of wings, many Diptera have a pair of club-like balancing organs, known as halteres, named after the counterweights that Greek long-jumpers used to assist their flight through the air. The order of Diptera encompasses 29 families, among them the following: Tipulidae, or crane flies, 3,000 species of which were distinguished by the entomologist C. P. Alexander; Culicidae, or mosquitoes; Chironomidae, or midges; Tabanidae, or horse flies; Asilidae, or robber flies; Syrphidae, flower flies or hover flies; Drosopholidae, vinegar flies or fruit flies.

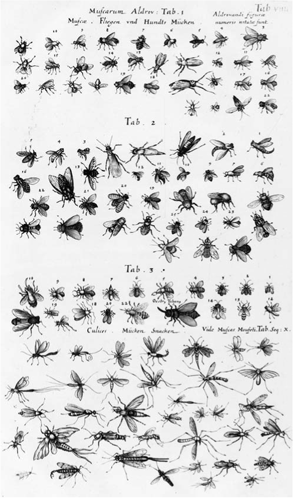

An array of types of fly on a page from an early German scientific book, reproducing an earlier illustration from Ulisse Aldrovandi. |

|

The most well known and widely dispersed families of Diptera, however, are the Muscidae, encompassing Musca domestica, the house fly, the stable-fly and the tsetse fly; Calliphoridae, or blow flies, the family that includes bluebottles; and Sarcophagidae, or flesh flies. It is this class of Diptera that is usually meant when we refer to flies. The reason for this is their feeding and breeding habits. The house fly lays its eggs in piles of dung or other decaying organic matter. The maggots that hatch from these eggs feed on the rotting matter until they pupate. The adult fly, though a promiscuous feeder, also has a taste for this kind of decaying matter. Blowflies and flesh-flies prefer to lay their eggs on dead bodies, including the bodies of humans. A sudden appearance of bluebottles (Calliphora vicina) in a house will usually indicate that there is a dead animal, such as a mouse or bird, somewhere at hand.

| The house fly, frontispiece to L. O. Howard, The House-Fly, Disease-Carrier: An Account of Its Dangerous Activities and of the Means of Destroying It (1911). |

Bluebottle maggots. |

|

The poet John Clare took great delight in flies and rapturously celebrated their co-tenancy in human spaces, their sharing of food and human lives:

These little indoor dwellers in cottages and halls, were always entertaining to me, after dancing in the window all day from sunrise to sun-set they would sip of the tea, drink of the beer, and eat of the sugar, and be welcome all summer long, they look like things of mind or fairries [sic], and seemed pleased or dull as the weather permits in many clean cottages, and genteel houses, they are allowed every liberty to creep, fly, or do as they like, and seldom or ever do wrong, in fact they are the small or dwarfish portion of our own family, and so many fairy familiars that we know and treat as one of ourselves.

Only to the most perverse or one in the greatest extremity of solitude (the desert anchorite, the Alcatraz lifer) does it occur to make a pet of this egregious pest. As both our constant fellow-traveller and provoking other, the fly is our familiar-stranger, our dis-similar. The fly is disconcerting in its capacity to make itself at home in our vicinity or our homes. Charles Olson evokes the sense of eviction aroused by an over-familiar fly: