Passenger on the Pearl

The True Story of Emily Edmonsons Flight from Slavery

WINIFRED CONKLING

ALGONQUIN YOUNG READERS

Published by

ALGONQUIN YOUNG READERS

An imprint of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

WORKMAN PUBLISHING

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2015 by Winifred Conkling.

All rights reserved.

PHOTO CREDITS

Getty Museum: Page .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

eISBN 978-1-61620-436-5

Contents

No man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake; and even that which he has not is at stake also. The life which he has may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may not be gained.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

My Bondage and My Freedom, 1855

ONE

A Mothers Sorrow

W HEN AMELIA CULVER met Paul Edmonson, she had no intention of ever marrying. Milly, as she was known, enjoyed spending time with Paul at church on Sundays, and the more she learned about him the more she cared for him, but she did not want to be his wife. She realized that she had fallen in love, but she was not concerned about love. Milly knew the truth: She was enslaved, and in Montgomery County, Maryland, in the early 19th century, her future did not belong to her.

At the time, Paul was enslaved on a nearby farm. They would not be able to live together as man and wife because they had different owners; but if they married, Milly and Paul would be able to see each other from time to time. Any children they might have would be born into bondage, owned by Millys master. Milly understood that the joy of marriage and family would end in heartbreak when her childrenher babiesgrew old enough to be torn away from her to work or to be sold in the slave market.

Despite what seemed like inevitable sadness, Paul asked Milly to marry him. She turned him down. Milly longed for love and family, but still more, she longed for liberty. I loved Paul very much, Milly said. But I thought it wasnt right to bring children into the world to be slaves.

Millys family and others at Asbury Methodist Church in Washington, D.C., urged her to reconsider Pauls offer, arguing that Paul was a good man and it was her Christian duty to marry and have children.

Paul proposed again, and this time she accepted.

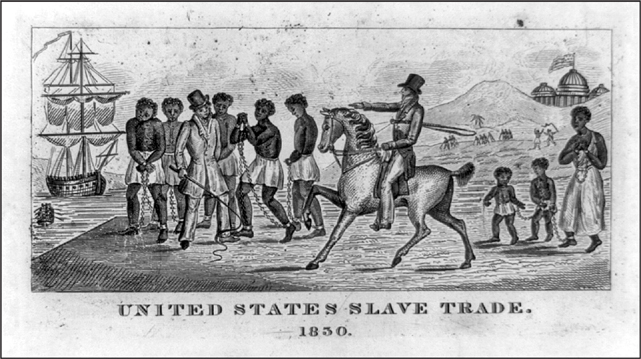

The copper plate used to make this engraving was discovered by workmen clearing the ruins of Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, which was built by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. After it was completed, the building stood for only three days before it was burned to the ground by anti-black rioters on May 17, 1838.

THIS CHILD ISNT OURS

As Milly had predicted, the painful realities of love within slavery soon followed. Well, Paul and me, we was married, and we was happy enough, Milly said. But when our first child was born I says to him, There tis now, Paul, our troubles is begun. This child isnt ours.

Oh, Paul, says I, what a thing it is to have children that isnt ours!

Paul, he says to me, Milly, my dear, if they be Gods children, it aint so much matter whether they be ours or no; they may be heirs of the kingdom. Milly tried to find peace in his words, but she still worried.

In the early years of her marriage, Milly and her young children lived with her mistress, Rebecca Culver, and Culvers married sister in Colesville, Maryland. It was not uncommon for an enslaved person to be freed when his owner died, and in 1821, Pauls owner freed him in her will. While many owners did not recognize slave marriages, Culver allowed Milly to work as a seamstress and live with Paul and their children on a local farm. Milly and Paul continued to have children, increasing Culvers wealth significantly.

I had mostly sewing, Milly said. Sometimes a shirt to make in a dayit was coarse like, you knowor a pair of sheets or some such, but whatever twas, I always got it done. Then I had all my housework and babies to take care of and manys the time after ten oclock Ive took my childrens clothes and washed em all out and ironed em late in the night cause I couldnt never bear to see my children dirty. Always wanted to see em sweet and clean. I brought em up and taught em the very best ways I was able.

Culver was mentally challenged and she was never able to manage her finances on her own. In 1827, Culvers brother petitioned the court in Montgomery County to have her ruled legally incompetent. The judge agreed and named her brother-in-law, Francis Valdenar, as guardian of her business affairs, which included oversight of Milly and her children.

By the mid-1830s, Milly had given birth to fourteen children, eight girls and six boys. She lived in constant fear that they would be taken from her. I never seen a white man come onto the place that I didnt think, There, now, hes coming to look at my children, Milly said. And when I saw any white man going by, Ive called in my children and hid em for fear hed see em and want to buy em.

In time, Millys fears were realized. As was common practice at the time, when any of her children reached age 12 or 13, he or she was taken from home and hired out to families in the Washington, D.C., area to live and work as domestic slaves. Their wages were sent back to Culver, who depended on this income.

Heartbroken, Milly begged her girls not to marry until they were free so that they would not become mothers of children born into slavery. She said, Now, girls, dont you never come to the sorrows that I have. Dont you never marry till you get your liberty. Dont you marry to be mothers to children that aint your own. Each of the Edmonson children, both the boys and the girls, shared their mothers belief that aside from their duty to God, nothing was more important than freedom.

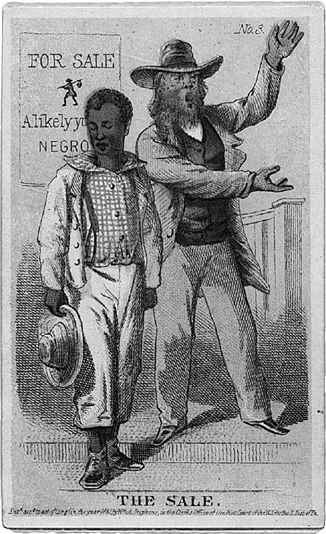

In 1863, Henry Louis Stephens (1824 1882) created this lithograph titled The Sale. The image is the third in a 12-part series of antislavery trading cards titled Journey of a Slave from the Plantation to the Battlefield. Abolitionists distributed the cards as a means of spreading their message.

AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Over the years, Valdenar had allowed the five oldest Edmonson sistersElizabeth, Martha, Eveline, Henrietta, and Elizato buy their freedom. They raised the money by taking on extra work and keeping a portion of their earnings, or by accepting money from family and friends. By 1848, Culver was in poor health, and she faced growing debts. Six of the Edmonson children were hired out at the time. There were no plans for their imminent sale, but the siblings realized that their futures were far from secure. Slave owners prized the Edmonson children for their honesty, intelligence, and morality; slave dealers prized them because they could demand a high price on the auction block. Would Valdenar sell one or more of them to pay Culvers expenses?

If they were sold, they could end up in fine homes working as domestics and butlers or they could end up in the Lower South, working as field hands or, worse yet, as fancy girls in the New Orleans sex trade. The two hired-out Edmonson sisters, Mary and Emily, had pale complexions and fine features, which meant that they could fetch a high price in the southern market. They were only 15 and 13 years old, respectivelya bit young to be sold into this line of work even by the standards of the time, but their true age did not matter. In such circumstances, slave traders were known to falsify documents and add a year or more to the reported age of their young female slaves.

Next page

ONE

ONE