If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who

profess to favor freedom, and deprecate agitation, are

men who want crops without plowing up the ground,

they want rain without thunder and lightning.

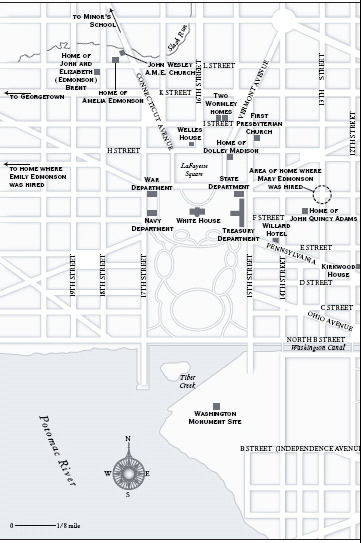

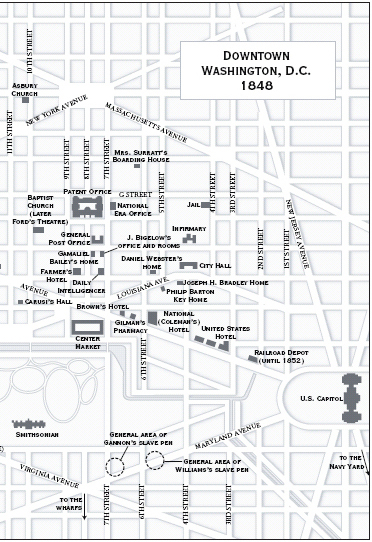

I n April 1848 an audacious escape on the Underground Railroad involved more than seventy fugitives and a fifty-four-ton schooner named the Pearl . It took place in Washington, D.C., certainly not the first place most people envision when picturing American slavery. But the plan was not organized solely for the purpose of aiding enslaved people in the nations capital to reach freedom. That could have been accomplished in the usual way, with smaller groups. This escape had evolved into a plan that would shock the country. For more than ten years, abolitionists had been lobbying for the end of slavery in the District of Columbia with no success. They now wanted to shine a light on the horrors of slavery and the slave tradea good number of those fugitives were on the verge of being sold to the labor-hungry cotton fields of the Lower Southin the capital of the country that had successfully waged a revolution in the name of democracy and self-determination.

Political compromise after the American Revolution landed the capital near the North/South divide that would eventually lead to a war of terrible death and destruction. Slavery was legal because it came with the territory. On July 16, 1790, when Congress passed legislation to cut land from Maryland and Virginia, both slave states, to form the District of Columbia, it provided that the laws from both would carry over into the new federal enclave, at least initially. At the time the new capital was created, slavery still existed in the North. However, those states could be characterized as a society with slaves, while the South had already evolved into a slave society.

In the 1830s a growing and newly radicalized antislavery movement emerged in the North; one of its primary goals was to end slavery in the District of Columbia. Unlike the Southern states, where ending slavery was seen as far more problematic because of constitutional protection for states to regulate their own affairs, the capital was under the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government. The United States Congress had the authority to pass a law that would abolish slavery and end the busy slave trade in Washington.

As local antislavery societies sprang up across the North, petitions began to flood Congress asking for the end of slavery in the federal enclave. But the rising heat of abolitionist rhetoric was met in kind with an adamant determination on the part of Southern legislators in Congress to hold tight to every inch of slave territory, no matter if it fell beneath the federal umbrella. The united front of the Southern legislators, who became widely known as the slave power, easily outmatched the handful of Northern legislators who were willing to support the end of slavery in the District of Columbia.

Even by 1800, significant changes had occurred in the Chesapeake region that impacted greatly on black people in and around the capital. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the labor-intensive tobacco crop that had formed the agricultural base of the area largely moved south, to be replaced by grains. Unlike tobacco, these crops required little maintenance and could easily be harvested by seasonal workers, leaving planters with a surfeit of slaves. Influenced by the same sentiments of the Revolutionary War period that led to the gradual emancipation of slaves in the North, a good number of slave owners freed their slaves, and the number of free blacks in the area, most particularly in Maryland, rose substantially. But that impulse did not last, especially after the invention of the cotton gin led to the Lower Souths huge expansion of cotton plantations. After 1808, those in the market for slaves could no longer look to Africa, because the transatlantic slave trade had been outlawed by Congress (though a lessened illegal trade continued). Instead, they looked to the tobacco slave states to provide laborers, and the value of American slaves rose.

Thus began an internal slave trade that historian Ira Berlin has named the Second Middle Passage. The first Middle Passage carried millions of slaves across the Atlantic from Africa to the New World. This new and wholly American Second Middle Passage forced an astonishingly large number of American slaves to migrate to the Lower South from the Upper South, an area that included Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Owners sold their increasingly valuable slaves to local traders, often one by one or two by two, rending black families. Slave traders stowed their purchases in public jails, privately owned slave pens, the attics and basements of their own homes, and holding cells provided by small inns and hotels. They collected slaves until they had assembled a sufficient number to make the trek south overland or by water. Few black families would be untouched by it.

This massive transfer of slaves further south, which also included a significant number of planters who walked their slaves south to cut new plantations out of the Kentucky and Tennessee wilderness, became one of the largest forced migrations in American history. Historian Barbara Jeanne Fields states that Maryland saw a steady hemorrhage of slaves. Until recently, a number of scholars have minimized the number of slaves who were forcibly relocated, and the subject has received little attention in accounts of Americas slave period. But recent definitive works by historians Robert H. Gudmestad, Steven Deyle, and Michael Tadman have established its magnitude. Between 1790 and 1860, at least one million slaves were transported from the Upper South to the Lower South; more than two-thirds of that total were removed by slave traders, while the others were marched farther south by their owners.

Not all area planters chose to sell excess slaves, at least not immediately. Instead, a significant number hired their slaves out to work for small farmers in the countryside and in the building and service trades in Washington, D.C. Many of the passengers who boarded the Pearl to seek new lives were hired slaves, including the six members of the Edmonson family who are profiled in this book. But hired slaves knew that they too were candidates for the slave trade, particularly when their owner died, or, all too often, for partition, when families were separated for distribution to heirs who often lived in disparate locales.

The high-volume sale of slaves led to increased activity on the Underground Railroad in the Upper South, and an organized cell had taken root in Washington by the early 1840s. But slaves had been fleeing their masters long before that, either to gain freedom in the North or to be with loved ones from whom they had been separated. Many were aided spontaneously along the way by free blacks, other slaves, and a small number of sympathetic whites, particularly members of the Society of Friends. But the more organized system of aid that sprang from the heightened antislavery fervor established a network to freedom that ensured help along the way.