Praise for Escape from Slavery

[Escapefrom Slavery] carries the uncalculating ring of truth.

San Francisco Chronicle

A chilling tale.

Karen Hunter, New York Daily Mews

How will the world respond to Francis Boks true story? Some will welcome its commercial profitability and entertainment value. And some will seek to change the world.

Anne Grant, Providence Journal

This is a powerful, exceptionally well-told story, equally riveting and heartbreaking. Although legal strides have been made, with the help of people like Bok, the persistence of slavery in the world makes this a work that cant be ignored.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Boks saga provides anothermore contemporaryperspective on slavery for Americans reckoning with their own troubling history of such inhumanity.

Booklist

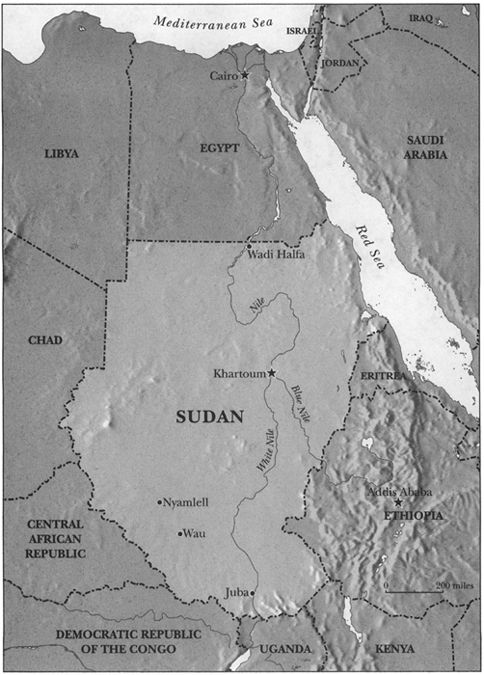

ESCAPE

FROM

SLAVERY

ESCAPE

FROM

SLAVERY

The True Story of My Ten Years

in Captivityand My Journey

to Freedom in America

FRANCIS BOK

WITH EDWARD TIVNAN

ST. MARTINS PRESS

ST. MARTINS PRESS  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

ESCAPE FROM SLAVERY . Copyright 2003 by Francis Bok. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Design by Phil Mazzone

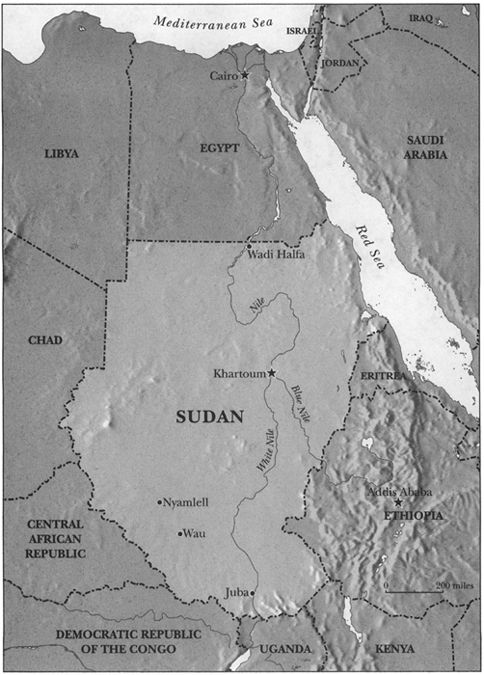

Map by Paul J. Pugliese

www.stmartins.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bok, Francis.

Escape from slavery : the true story of my ten years in captivityand my journey to freedom in America / Francis Bok, with Edward Tivnan.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4299-7101-0

1. Bok, Francis. 2. Sudanese AmericansBiography. 3. SlavesSudanBiography. 4. SlaverySudan. 5. SudanBiography. I. Tivnan, Edward. II. Title.

E184.S77B65 2003

305.567092-dc21

[B]

2003047132

For my mother, my two sisters, and my brother but especially for my father, who always told me I would do something important in life. Also, for those who are still slaves and those who are fighting for freedom in Sudan.

CONTENTS

ESCAPE

FROM

SLAVERY

CHAPTER ONE

THE RAID

I have told the story many times about that day in 1986, when my mother sent me to the market to sell eggs and peanuts: the day I became a slave. But, as I begin to tell my story here, I realize that I have never before discussed how happy my life was just hours before it changed forever. Too many bad memories left no space for the good ones. Yet, before the misery, loneliness, and constant fear that my childhood became, before the ten years when my only friends were Giemma Abdullahs goats and cows, I remember my fathers farm in southern Sudan, where every day seemed full of family, friends, and love. I was only seven years old in 1986, and now that I am in my twenties I have many questions about those days, which that little boy in far-off Africa cannot answer. But even as a mere seven-year-old, I was aware that my life was good and might get better.

It was not so for everyone in our village, and I felt sorry for the poor who lived there. Sometimes people would come to our farm to beg for milk and cheese. We had plenty of both; we had chickens, goats, sheep, and cows; we had beautiful green trees with ripe yellow mangoes that we could pick off and eat, and coconuts as big as your head. My family grew peanuts and other kinds of beans. We were surrounded by green fields of sorghum where I would play with my sisters, Amin, who was twelve, and baby Achol, who could barely walk. We lived in two large housesone for the men, the other for the womenmade from mud and topped by straw roofs shaped like upside down cones. Even the cattle had their own hut with a roof of straw to keep them warm in the winter and to protect them from the rain. Our farm was full of lifeanimals, plants, familiesand there a little boy could do almost anything that he wanted.

I did not go to school. No one in my family had any formal education; I dont think I knew what a school was or what happened there. I had heard the word school, but all it meant to me was a place that some kids from the village had been sent to in Juba, the capital city of southern Sudan, near the borders of Zaire and Uganda. In Gourion, my village, there was no school, and like most little Dinka boys, I spent my days in a pair of shorts, nothing but underwear really, no shirt, barefoot, playing with my sisters and friends.

We played alweth: We would run off and hide in the fields, leaving one of us to find the others. And when he found someone, he would chase them and try to touch themhide-and-seek, Dinka style. We also had our own kind of baseball or cricket, called madallah. All we needed was a stick and a chunk of rubber the size of a hockey puck, made either from the heel of an old shoe or from an old car tire. Then we made teamsfour on a sideand someone threw the puck and another hit it, and someone else tried to hit it back, as hard as possible. The point was to keep the rubber in the air. Whoever missed it, lost. Madallah is a game of energy and power, and I loved playing this game.

If I was lucky, my eighteen-year-old brother JohnI called him by his Dinka name Bukwould let me watch him and his friends at their games. In the evening, when it was cooler, the big kids played jeddi. Ten boys, five to a side. Each boy would bend a leg at the knee and hold it by the ankle, jumping around on one leg within a big circle. The aim was to get one person on your side past the others by blocking and preventing them from pushing him over. My little friends and I also played jeddi. If we got a good game going, other kids would come to watch and want to play. That would increase the excitement of the game, and all of us would try even harder to impress the audience.

One of my favorite activities was making little cows. The Sudanese measure wealth in terms of how many cows you have, and little boys like me created our own herds out of the clay from the ground. My brother was very good at this, and he taught me how to take a handful of mud and sculpt it into a miniature cow. My friends and I spent hours sitting in the village under a tree making animals, sometimes goats and sheep, but mainly cows. Days passed unnoticed; in the morning I would begin molding the clay and suddenly it was time to go home to eat. Each of us made a shelter for our cattle, which we were allowed to leave right there in the village in a special place until the next sculpting session.

But what I liked to do most was follow my father around the farm. If he was digging in the fields, I began digging. If he was pulling sorghum grasses from the ground, I tried to pull them, too.

Go play with your friends! he would say. But I wanted to help my father, and he seemed to be pleased that I liked to work at his side. I felt my fathers love every day. He had eight children, four older than this eager seven-year-old running in his shadow. But he always talked to me, encouraged me. He often would hug me and hoist me up on his shoulders and let me ride him on his visits to his friends in the village. What do you want, Piol? he asked me every night, and What do you need, Piol? every morning. That he had named me Piol was an honor. It was a favorite name in his family, the Dinka word for rain. Francis was my Christian name, but in my village I was Piol Bol (my fathers name) Buk (his fathers name).

Next page

![Saint Francis de Sales [Sales - The Saint Francis de Sales Collection [15 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/266802/thumbs/saint-francis-de-sales-sales-the-saint-francis.jpg)

![Saint Francis de Sales - The Saint Francis de Sales Collection [15 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/161144/thumbs/saint-francis-de-sales-the-saint-francis-de-sales.jpg)

ST. MARTINS PRESS

ST. MARTINS PRESS  NEW YORK

NEW YORK