Bidibidobidiboo , 1996

The Aesthetics of Failure

My work can be divided into different categories. One is my early work, which was really about the impossibility of doing something. This is a threat that still gives shape to many of my actions and work. I guess it was really about insecurity, about failure. We can have a chapter here called Failure.

GROWING up in Padua, Italy, in an uneducated, lower-class family of five during the 1960s and 70s, Cattelan dreamed of escaping life at little more than a subsistence level. His father was a truck driver and his mother a cleaner. The fact that she suffered from lymphatic cancer through most of his childhood and adolescence only amplified the sense of despair to a traumatizing degree.

It was during this time that Cattelan began to experiment with a very personal, idiosyncratic form of industrial design, creating one-off, semianthropomorphic objects. A reluctant participant in the overheated world of design in Italy, he nevertheless earned some recognition in it, creating a glass-and-iron table called Cerberino that is still in production today. In an act that reflected his general disregard for authority as well as his economic constraints, Cattelan managed to mail the catalogues for free with purloined postage. But the decision to pursue a full-time career as a visual artist only happened, he claims, after encountering a self-portrait on mirror by Arte Povera artist Michelangelo Pistoletto in a small gallery in Padua. He was twenty-five years old at the time and refers to this incident as the epiphany that changed the course of his life. Having grown up in Italy where artat least religious artis ever present, the idea that something in the aesthetic realm could be so startlingly relevant in its direct engagement with the viewer moved him deeply. Detecting his profound curiosity (and clear lack of knowledge), the gallerist lent him books on contemporary art, and thus his informal, self-directed education about art began in earnest.

Cattelan created what is considered to be his first unequivocal work of art in 1989 Lessico familiare (Family syntax, In this staged black-and-white image, he depicted himself with his hands forming the shape of a heart over his bare chest. Framed in ornate silver, the work was originally exhibited like a traditional marriage portrait on a decorative side table with two candelabra and a small carved bust on an embroidered doily. The entire ensemble, with its altarlike arrangement, bespoke a petit-bourgeois ambience that Cattelan was both emulating and upending, as his gesture of affection in the photograph is simultaneously endearing and pathetic. Despite its allusions to a wedding picture, the image shows the artist all alone, the heart shape decidedly empty.

The reference in the title to a family syntaxa prescribed vocabularysuggests the artists troubled attraction to an ideal that had always eluded him. The use of his own image indicates how, without being directly autobiographical, Cattelan drew on his own emotional and psychological experiences to inject his art with potential meaning. This is a strategy he would continue to exploit throughout his early work. His goal, however, was not to invoke specific events or individuals but rather to summon up states of mind or emotions that would resonate in the present. While the work is not directly about him, he uses himself as an example, as a character whose foibles and trials invoke an empathetic identification on the part of the viewer. In the cover letter accompanying his 1987 pitchbook, he wrote (in poorly rendered English): My name is Maurizio Cattelan, from Italy. I am an artist. The issue is showing an image of my work before the 1987. Ive been using a different kind of technician to express myself. Now, often more, in my work Im caring about the ironic-disobedient-childish aspects of my personality.

Cattelans childhood memories provided vivid fodder for his self-proclaimed concentration on bad behavior at this early stage in his career. His fraught relationship to his elementary-school education, an environment of flourishing insecurity, informed a number of works from the early 1990s that emphasized the drudgery of repetition and its punitive applications. ), Cattelan imitated the oft-used school punishment that requires a child to write the same sentence over and over, such as Cheating is bad, or I will not forget my homework. He had the following statement inscribed repeatedly on twenty-nine sheets of lined paper: Fare la lotte in classe pericoloso (Fighting in class is dangerous). When it was then corrected in red inkchanging the in to a dithe meaning of this declaration shifted dramatically, to Class struggle is dangerous. The artists playful realignment of the message simultaneously constitutes an ironic response to the very real social upheavals in Italy at the time and intimates a more genuine resistance to the toils of endless, unsatisfying labor.

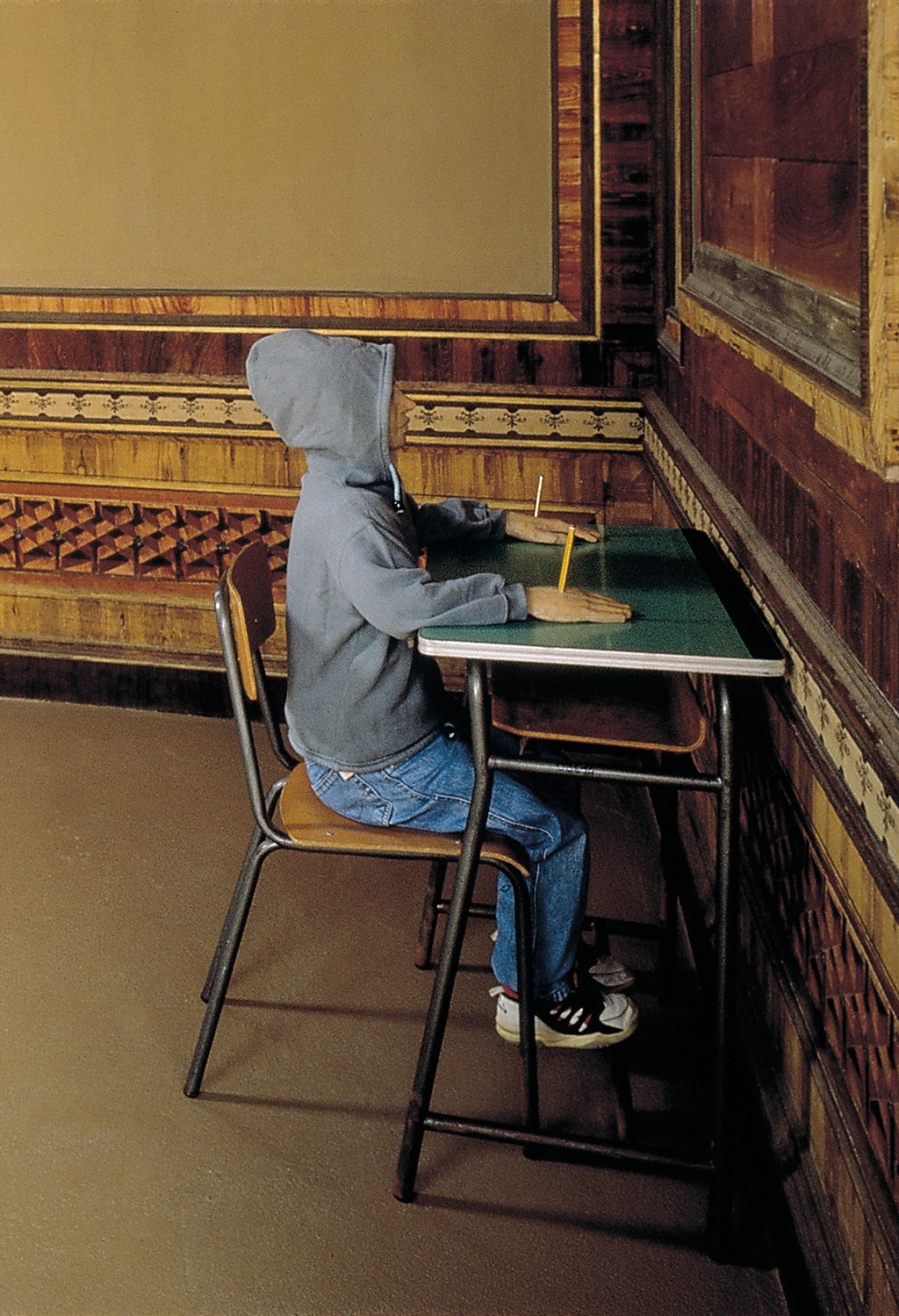

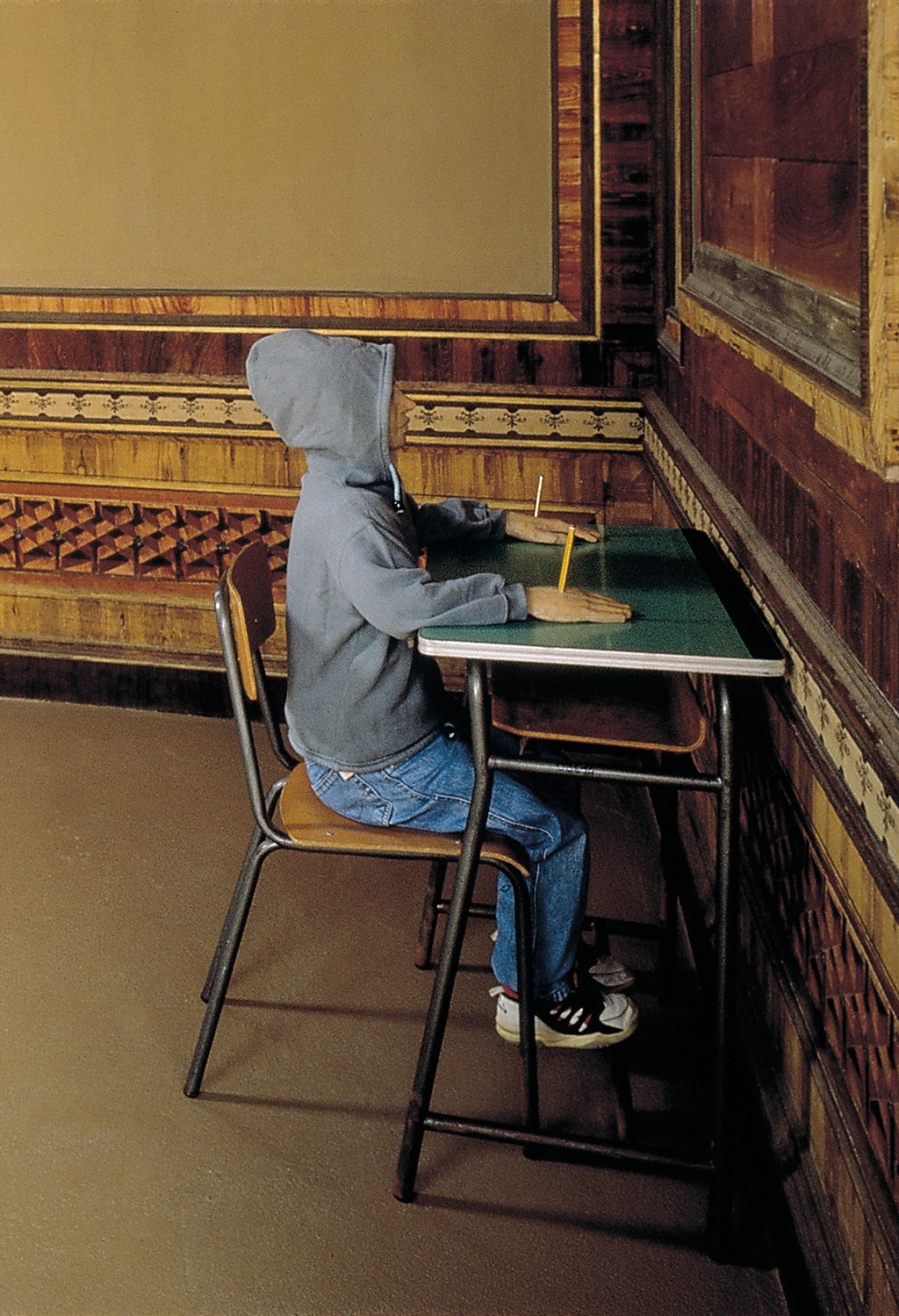

Charlie Dont Surf, 1997

The theme of academic repression and the anxieties that accompany it persisted in Cattelans output, culminating in the simultaneously poignant and gruesome sculpture Charlie Dont Surf (1997, fig. 3,

On the occasion of his first solo exhibition, held at Galleria Neon in Bologna in 1989, Cattelan was evidently so disappointed with his production that, in place of all the works he intended to show, he posted on the locked front door of the gallery a simple placard that read Torno subito , or Be back soon ( While demonstrating his failure to produce the requisite salable object for a gallery show, the untitled work nevertheless announced the kind of risk-taking path that the artist would follow from this point on, balancing, as it were, total irony and a kind of deadpan honesty.

For Cattelans debut in New York, where he moved in 1993, he deployed a similar strategy of evasion and denial. Unable, he claimed, to conceive of any good ideas for his solo exhibition at Daniel Newburg Gallery in 1994, he installed an ornate chandelier accompanied by a live donkey, a common symbol for stupidity, to represent his lowly place within the art world. While presented as an off-handed joke, Warning! Enter at your own risk. Do not touch, do not feed, no smoking, no photographs, no dogs, thank you (fig. 4) nevertheless invoked a significant artistic pedigree. It no doubt referenced Joseph Beuyss first exhibition in New York, in which he lived on site at the Ren Block Gallery for one week with a live coyote in a shamanistic ritual of coexistence. The donkey itself, which would become a favored motif in Cattelans work, also recalled Jannis Kounelliss groundbreaking installation of live horses at Galleria LAttico in Rome in 1969. Though steeped in self-ridicule, the exhibition at Daniel Newburg, with its allusions to Beuys and Arte Povera, also made clear the artists aspirations for a place in contemporary art history and the seriousness of his enterprise, despite all appearances otherwise.

Warning! Enter at your own risk. Do not touch, do not feed, no smoking, no photographs, no dogs, thank you , 1994

The strategy of hiding in plain sighta manifestation of Cattelans love/hate relationship with public exposurewas one that he would return to later in his career. On the occasion of his first solo exhibition at the venerable Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, a milestone in any artists professional life, he presented a life-size sculpture of a baby elephant wearing a white sheet with holes for its eyes and trunk. Compelling in its ambiguity, Not Afraid of Love (2000, fig. 5, This performative action represented a calculated refusal to exhibit within such a defining nationalistic context while also signaling his purported inability to produce. Cattelan admitted failure before the fact and so protected himself against inevitable and always unpredictable criticism. His staging of avoidance was also clearly a ploy, a way to make art out of insecurity with a healthy dose of humor.