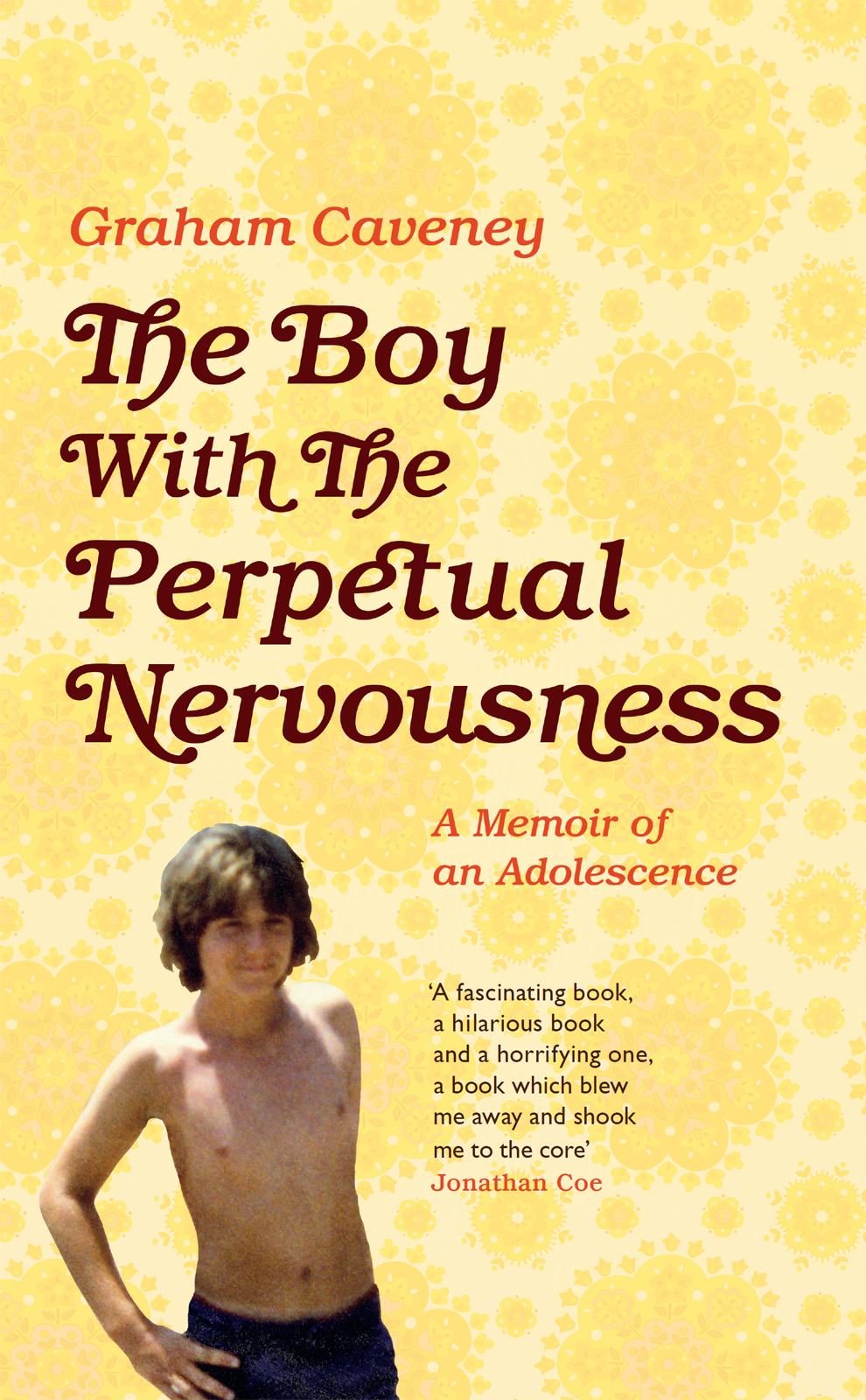

The Boy with the

Perpetual Nervousness

A Memoir of an Adolescence

GRAHAM CAVENEY

PICADOR

To Anja Rutten, with thanks

How dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

... when my pen leaks, I think awry. And who will give me back the good ink of my school days?

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Reverie

Contents

She says things like Neural Pathways, and Emotional Processing, and Some Success with Veterans from the Vietnam War. She says things get frozen, shelved, not properly digested. There is a bagatelle behind my eyeballs. She says follow my finger. I follow her finger. It is pulling back the spring on the pinball machine in my frontal lobe. Recall the scenes, she says. Recall them as though they are on a video loop. Got that? Video. You can control what happens. You can pause or fast-forward or rewind. Its a black-and-white movie, loosely autobiographical: based on actual events, as the blurbs always put it.

I am playing Me: typecasting, you might say. I am fifteen and I have bad skin. I have bad skin and I have long hair. My hero at the time was Jim Morrison from The Doors and I reckoned that on a dark night, in a fog, at fifty paces, I might be able to pass for him. This was 1980. Punk had already happened, but not in that Ground Zero, Road to Damascus way that is so often attributed to the arrival of The Clashs / the Pistols / The Damneds first album. Not for intense and bookish young boys from Accrington, anyway. For us, for me, punk was still partly a rumour, even after its demise. We caught it as it was leaving the building. The memory of the Sex Pistols Manchester Free Trade Hall gig was mythic, not singular. It was like the Kennedy assassination or the moon landings, both ancient and crushingly modern. (One day, technology will enable us to prove conclusively just who did attend this event, and that day will be a day of terrible reckoning. Names will be broadcast on tannoys throughout the city, and grown men will weep.)

Where was I? Thats right, following her finger. Her, by the way, is Julie, my therapist. It is 2012 and I am having post-rehab therapy for the issues that led to my addictions. There used to be scare quotes around both these words issues and addictions but not any more. Now they just trip off the tongue with all the sincerity we can muster. She carries on with the finger stuff, the one next to her thumb, right hand, fully extended. As it moves back and forth she is asking me to remember details the more detailed the details the better. The name for this treatment is EMDR Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy. The idea and there is an impressive amount of evidence to back this up is that traumatic and distressing events are not processed properly at the point of trauma (it is, if you like, precisely what is traumatic about them). The event(s) thus become buried, only to surface later as neurosis, pathology, disorder. It has an almost tactile specificity to it, this EMDR stuff, as though my brain is Play-Doh and needs to be re-moulded. Its also had some remarkable success, particularly in the States, and that always makes me suspicious. I may have PTSD, its my most recent diagnosis. It would make sense, from what Ive read. I am, as they say, textbook. And if you have PTSD then you need EMDR treat one acronym with another. What were doing is time-travel. My mind is a Tardis and somehow my experiences can be unlocked and re-processed through this side-to-side eye-movement recall.

And it is true that something is shifting. I am remembering one specific incident within an incident the feel of bristles on my face. The movie starts to seep into colour. There is a dissolve, a rearrangement of dimensions and perspective. That bit looks sharper, the angle on the bed. There is a softer focus on the lens. Something about it strikes me as ludicrous, it reminds me briefly of a Carry On film. I start to laugh. Julie smiles at my laughter, encouraging me: This is your film now, you can make it into a comedy if you like, its yours to view however you want...

I am laughing hard now; a contained hysteria that I can feel at the back of my throat. This is absurd. There is a man, look at him! He has hair on his back... hes grunting... Hes... Theres a boy... Underneath him... The mise-en-scne is off. The set is made of cardboard.

Julie is staying with me, calm, alert. Im changing my tenses: It was... becomes It is.... I switch pronouns, I to he to it. Projections onto the back of my closed eyelids; faster and slower at the same time. Its like old newsreel clips: Path, home movies. Clips of people from the silent era walking and waving in that disjointed flickering motion. For some reason I associate old celluloid footage with baseball (Babe Ruth?), although I am not an American and have never seen baseball. The images slow down. Theres an overdub with the kind of hallucinatory soundtrack that gets used in sixties acid indie films, the kind with Peter Fonda, maybe directed by Monte Hellman. And... action!

His hand is on my cock, his cock is on my stomach, his mouth is on my mouth. He is masturbating. Theres a boy who looks like me. Hes lying on his back. Im looking down at him from the ceiling. And cut.

Dissociation is one of those terms that has entered our collective wisdom in ways that I am both thankful for and irritated by. Thankful in that it gives legitimacy to the experience of sexual trauma. Irritated that the experience can be reduced to a one-word tickbox. The ambivalence about being diagnosed speaks to the condition itself. Who doesnt want their experience to have a description? Yet who doesnt want to be more than their diagnosis? Dissociated it is then, for the moment, and amongst other things.

It is certainly my experience that when reality is overwhelming, unprocessable, non-computable, our minds simply take us somewhere else. We replace unacceptable truths with fantasies fantasies which may have a truth of their own, yet which place us at odds with the cold unforgiving empiricism of the-world-as-it-is. Thanks to genre fiction, Hollywood and popular psychology, we now expect the Mad and the Dangerous to have rationales of their own. The fucked-up kid is our new femme fatale. The kid locked in a strangers basement. The kid who witnesses his mothers murder. The kid forced to participate in genocide. We love our fucked-up kids nearly as much as we despise the adults they become.

What we know is that trauma is never something that is simply left behind, like blood at the scene of a car crash. Rather it is something that the survivor, the sufferer, carries within them; the wreckage that is part of their self. The first time that I heard the term dissociation was in relation to chemistry, whereby it describes the process of ionic compounds being broken down into smaller particles and ions. I remember sitting in chemistry labs as a kid watching obscure-sounding acids or salts being dissolved in water, and watching this kaleidoscopic process of crystallization as each constituent part... what? retreated? was liberated? got banished from? all the others. I remember asking the teacher, a disappointed man named Mr Stokes, if these dissociated parts could be reunited or reintegrated. He assured me that, with a few exceptions, they could.

Of course, this idea of a traumatized childhood carries with it the implication that there could be such a thing as a non-traumatized childhood. Readers of Freud will know that, for him, childhood was itself a kind of trauma a time when the infant has to relinquish his tyranny over his parents and be coerced into the dreaded disillusion of the Reality Principle. According to this model, no one emerges unscathed. We become who we are by abandoning our most primal desires, being born again into the laws of our Father (societal norms, non-incestuous desire, relationships with bodies other than our own). The traumatized child then is nothing more than a tautology, a description of an inevitable process of disenchantment.