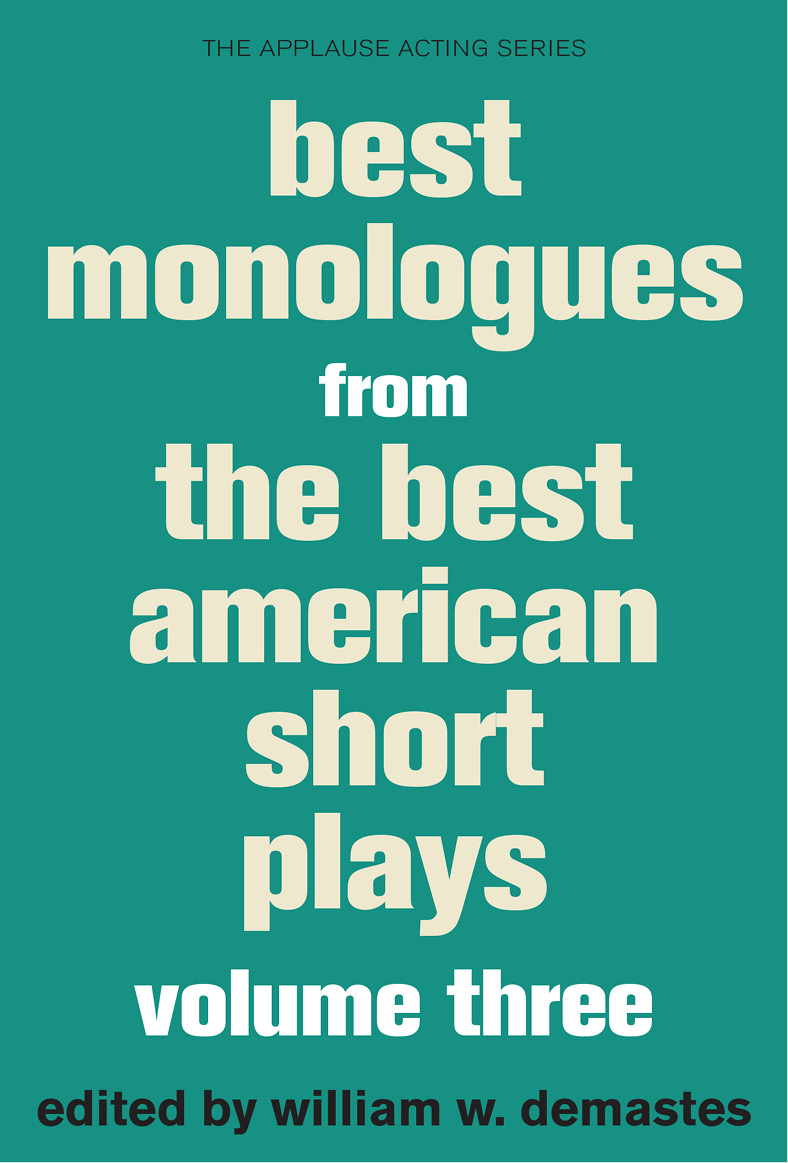

Copyright 2015 by William W. Demastes

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Published in 2015 by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books

An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

Trade Book Division Editorial Offices

33 Plymouth St., Montclair, NJ 07042

Credits and permissions can be found in Credits and Permissions, which constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Lynn Bergesen

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Best Monologues from The Best American Short Plays / edited by William W. Demastes. volumes cm. (The Applause Acting Series)

ISBN 978-1-4803-3155-6 (volume 1) ISBN 978-1-4803-8548-1 (volume 2) ISBN 978-1-4803-9740-8 (volume 3)

1. Monologues, American. 2. American drama20th century. 3. American drama21st century. I. Demastes, William W., editor of compilation.

PS627.M63B47 2014

812'.04508dc23

2013041949

www.applausebooks.com

contents

Speech Acts

Youre fired. I baptize you in the name of... Give me two snow cones. Those are ugly shoes. Oh, that this too, too, solid flesh would melt, thaw, resolve itself into a dew. Language is a funny thing, serving humanity in any number of ways by helping us as we struggle to find common cause and establish community in an increasingly crowded but ever alienating world.

Renowned philosopher of language J. L. Austin (19111960) spent a career trying to do what most philosophers of language try to do: make sense of human language. He famously popularized the term speech act, identifying language as something that has performance qualities even though speech doesnt actually act in any way that we typically describe as action. It doesnt move things, or touch things, or do much of anything like that. Stop talking and do something is a typical response to the perennial advice giver. Theres a line between doing and talking that we all pretty much understand. The problem with that common perception, and one that Austin recognized, is that some forms of speech do do things that can be called acts.

Telling someone theyre fired certainly has an impact almost as stunning as being hit by a hammer. Declaring someone baptized, or married, or divorced are pretty significant transformative pronouncements, literally converting someone from one kind of person into another. Asking for a snow cone is a gesture that one hopes will lead to a refreshing response, especially on a hot summer day. Criticizing someones shoes may actually encourage the person to change into something more appealing. These words interact with the physical world and actually have some sort of influence on our surroundings. Theyre speech acts.

But what about wishing our too, too imperfect bodies would just dissolve and somehow leave nothing behind but the perfection of our souls (in a perfectly idealized world where nothing corrupts or decays)? Is it possible that these opening lines to Hamlets famous first monologue/soliloquy may actually do something? Perhaps its a perfectly worded sentiment that summarizes exactly how you sometimes feel about this mixed-up, jumbled-up, shook-up world, and it speaks to exactly how you want to deal with it: by simply fading away. Or maybe you never thought about the world in that way at all. Maybe youve been living with some queasy feeling about the world for some time now, but never quite knew what it was you were feeling. Maybe you didnt quite know what it was you were feeling because you never quite knew how to put it into words. Now, however, youve seen your thought perfectly expressed (though Shakespeares poetic phrasing might not be how you would have said this), and now you move forward in life with greater focus because now you know with precision what vague, queasy sentiments had previously been coursing through your veins. Oh, that this too, too solid flesh would melt has become for you a transformative speech that gains the name of action by actually altering or focusing what you believe and therefore who you are.

Speech acts. Im using Shakespeare here because he helps me show what a great phrase speech acts is when it comes to describing what happens onstage when actors arrive and find an audience willing to attend to what they have to say. The stage is the space that relies on speech to carry out action. Physical stage actions do occur, of course. People do get into each others space; they do move about in a choreography of significance. Props are used, and people do interact with them. Physical gestures can make or break an acting style. People touch, gesture, exit. But in the theater it is the language that carries the day. We go for the words.

And when we go to the theater, we go to hear those words spoken by someone, bringing language into direct contact with the physical and engaging the physical before our very eyes. Novels, poetry, the newspaper all have speech acts embedded in them, of course. And the streets, our offices, shopping centers, our homesthey are all full of speech acts. But the theater gives us pause to think about these words, words, words.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me. Really? Words can break spirits, destroy confidence. They can also build hope and incite great acts of heroism. Playwrights know this, and so do theater audiences. Otherwise, why go? How about whats in a name? Call a rose skunk weed and maybe it really wont smell as sweet. How easy was it for Romeo to deny his name (or his father)? Romeo he was, and a Montague he remained, despite his naive teenage decision to get out from under the curse of that name. Consequences follow. Words matter and carry clout every bit as dangerous as a hammer or crowbar. This too playwrights know.

The theater, in short, is the laboratory for speech acts. Authors string words together with the complex goal of pulling together disparate audience members into a single attentive community. Even if the goal is to bring everyone together for one single moment of unified laughter, or perhaps a gasp of surpriseeven if that small effect is the goal, then the playwright has taken on a pretty daunting and very complex task.

Sometimes playwrights have a political or personal agenda in mind and use the theater to transform an audiences beliefs and attitudes. Is it possible to eliminate or at least minimize such destructive forces as racism, sexism, or nationalism by changing peoples beliefs and attendant actions? If so, then speech acts have had their impact.

When it comes to thinking about these transformations, it is generally very difficult to distinguish between conscious and unconscious behavioral shifts. There is little doubt, however, that unconscious shifts have more profound and longer lasting effect. And they are harder to generate as well. So, for instance, walking out of a theater and realizing that Native Americans are a nearly forgotten but still mistreated minority may result in immediate corrective action of one sort or another. We could call that a soft-wiring alteration. But to be exposed in subtle but visceral ways to the persistent, grinding dehumanization that generates discrimination, and to have it somehow sink beneath our consciousness and into our unconscious beings, thats a hard-wire change. How to do these things?