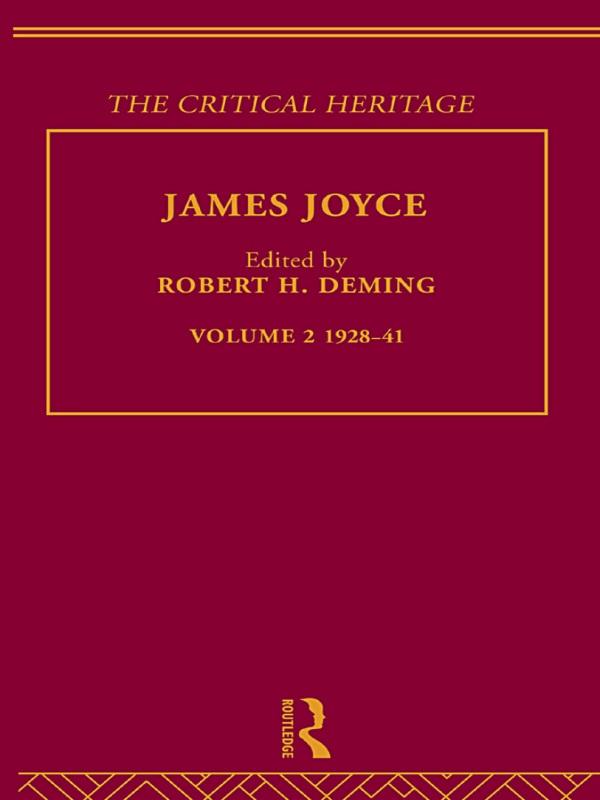

Deming - James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41

Here you can read online Deming - James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Routledge, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41

- Author:

- Publisher:Routledge

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published in 1970

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

Compilation, introduction, notes and index 1970 Robert H.Deming

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

ISBN 0-203-19667-8 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-19670-8 (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0-415-15919-9 (Print Edition)

General Editor: B.C.Southam

The Critical Heritage series collects together a large body of criticism on major figures in literature. Each volume presents the contemporary responses to a particular writer, enabling the student to follow the formation of critical attitudes to the writers work and its place within a literary tradition.

The carefully selected sources range from landmark essays in the history of criticism to fragments of contemporary opinion and little published documentary material, such as letters and diaries.

Significant pieces of criticism from later periods are also included in order to demonstrate fluctuations in reputation following the writers death.

October 1928

1924

Letter to his brother (7 August 1924), quoted in Ellmann, James Joyce, pp. 58991, and in Ellmann, Letters, Volume III, 1966, pp. 1026.

An extract from a long letter concerning Ulysses and Work in Progress.

I have received one instalment of your yet unnamed novel in the Transatlantic Review. I dont know whether the drivelling rigmarole about half a tall hat [Finnegans Wake, p. 387] and ladies modern toilet chambers [Finnegans Wake, p. 395] (practically the only things I understand in this nightmare production) is written with the deliberate intention of pulling the readers leg or not. You began this fooling in the Holles Street episode [the Oxen of the Sun episode] in Ulysses and I see that Wyndham Lewisimitates it with heavyhoofed capering in the columns of the Daily Mail. Or perhapsa sadder suppositionit is the beginning of softening of the brain. The first instalment faintly suggests the Book of the Four Masters and a kind of Biddy in Blunderland and a satire on the supposed matriarchal system. It has certain characteristics of a beginning of something, is nebulous, chaotic but contains certain elements. That is absolutely all I can make of it. But! It is unspeakably wearisome. Gormans book on you [James Joyce, The First Forty Years] practically proclaims your work as the last word in modern literature. It may be the last in another sense, the witless wandering of literature before its final extinctionI for one would not read more than a paragraph of it, if I did not know you.

What I say does not matter. I have no doubt that you have your plan, probably a big one again as in Ulysses. No doubt, too, many more competent people around you speak to you in quite a different tone Why are you still intelligible and sincere in verse? If literature is to develop along the lines of your latest work it will certainly become, as Shakespeare hinted centuries ago, much ado about nothing. Ford in an article you sent me suggests that the whole thing is to be taken as a nonsense rhythm and that the reader should abandon himself to the sway of it. I am sure, though the article seems to have your approval, that he is talking through his half a tall hat. In any case I refuse to allow myself to be whirled round in the mad dance by a literary dervish.

1928

Extract from River Episode from James Joyces Uncompleted Work, Dial, lxxxiv (April 1928), 31822; also appeared as the Preface to Joyces Anna Livia Plurabelle (1928), pp. viixix and in Our Friend James Joyce (1958) by Mary and Padraic Colum, pp. 13943.

Anna Livia Plurabelle is concerned with the flowing of a River. There have gone into it the things that make a peoples inheritance: landscape, myth, and history; there have gone into it, too, what is characteristic of a people: jests and fables. It is epical in its largeness of meaning and its multiplicity of interest. And, to my mind, James Joyces inventions and discoveries as an innovator in literary form are more beautifully shown in it than in any other part of his work.

But although it is epical it is an episode, a part and not a whole. It makes the conclusion of the first part of a work that has not yet been completed.

And so, like a river, it has gone on, and expanded, and gathered volume. It is the same River that Stephen Dedalus of The Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man looked upon.

[quotes from A Portrait, ch. IV, p. 167, and from p. 216]

So the later prose begins, and at once we are in the water as it bubbles and hurries at its source. The first passage gives us the sight of the River, the second gives us the River as it is seen and heard and felt. The whole of the episode gives us something besides the sight and sound and feeling of water.

It is this range we get in this episode: over and above the sight and sound and feeling of water there is in Anna Livia Plurabelle that range of images and thoughts, those free combinations of words and ideas, that might arise in us, if with a mind inordinately full and on a day singularly happy we watched a river and thought upon a river and travelled along a river from its source to its mouth.

But in this episode the minds range has its boundary: the range is never beyond the river banks nor away from the city towards which the river is making its slow-moving, sometimes hurrying way. Dublin, the city once seventh in Christendom, Dublin that was founded by sea-rovers, Dublin with its worthies, its sojourners, its odd characters, not as they are known to the readers of history-books, but as they live in the minds of some dwellers by the Liffey, is in this episode; Dublin, the Ford of Hurdles, the entrance into the plain of Ireland, the city so easily taken, so uneasily held. And the River itself, less in magnitude than the tributary of a tributary of one of the important rivers, becomes enlarged until it includes hundreds of the worlds rivers. How many rivers have their names woven into the tale of Anna Livia Plurabelle? More than five hundred, I believe.

[quotes from p. 202]

There will be many interpretations of Anna Livia Plurabelleas many as the ideas that might come to one who watched the flowing of the actual river

[the critic adds his own recollections]

I feel in this tale of Anna Livia Plurabelle the mystery of beginnings as it is felt through, as it combines with, a hundred stray, significant, trifling things.

Its author, the most daring of innovators, has decided to be as local as a hedge-poet. James Joyce writes as if it might be taken for granted that his readers know, not only the city he writes about, but its little shops and its little shows, the nick-names that have been given to its near-great, the cant-phrases that have been used on its side-streets. This localness belongs to James Joyces innovations: all his innovations are towards giving us what he writes about in its own atmosphere and with its own proper motion. And only those things which have been encountered day after day in some definite place can be given with their own atmosphere, their own motion.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41»

Look at similar books to James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book James Joyce. Volume 2: 1928-41 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.