Contents

Guide

Page List

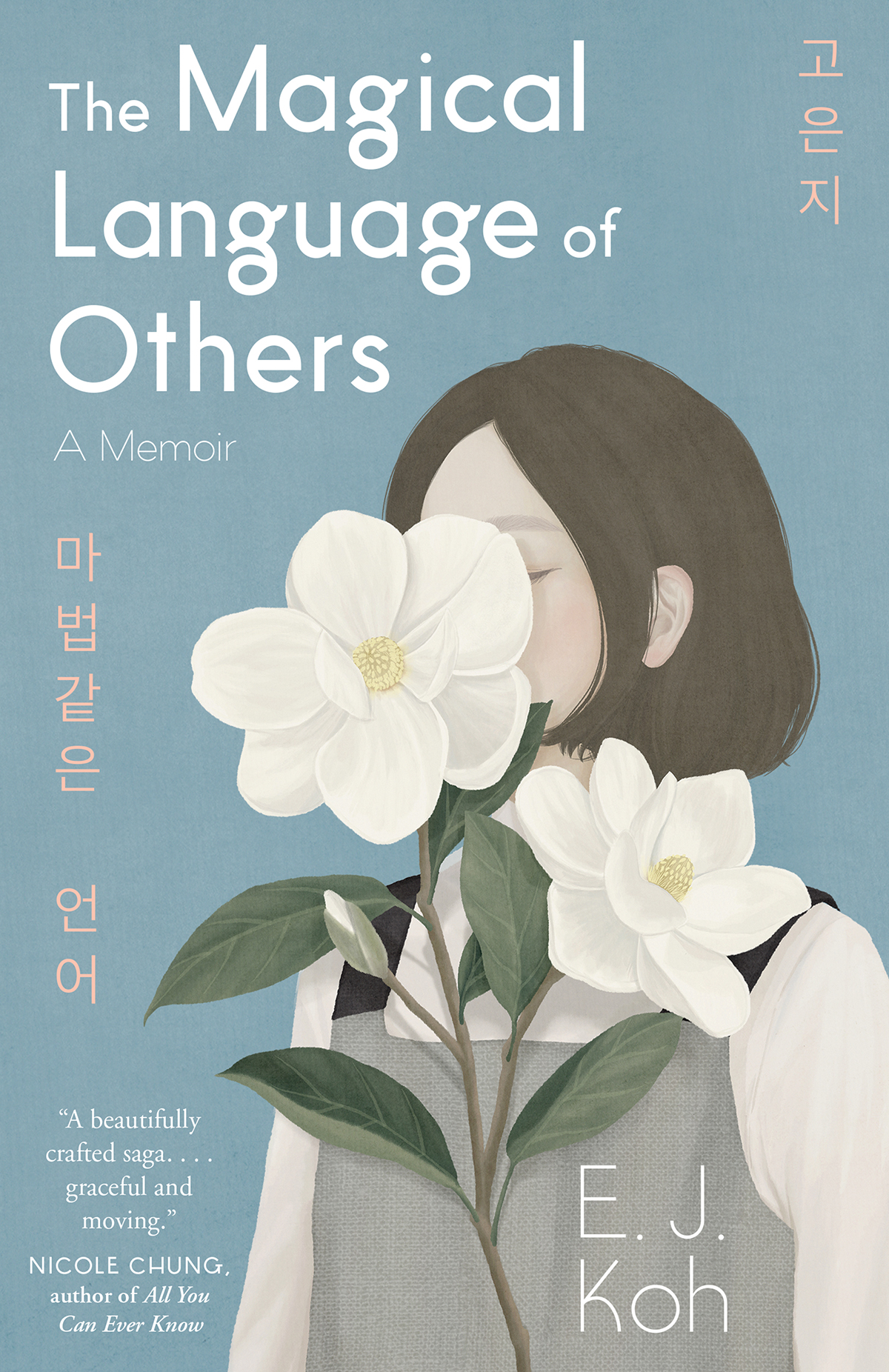

The Magical Language of Others is a beautifully crafted saga, and a testament to how the most complicated, often elusive truths and inheritances can shape us and reverberate across generations. Anyone who has ever wondered about their own family history, or sought to understand how it comes to bear on their most intimate relationships, will find much to ponder and relate to in E. J. Kohs graceful, moving memoir.

NICOLE CHUNG,

author of All You Can Ever Know

The Magical Language of Others is an exquisite, challenging, and stunning memoir. E. J. Koh intricately melds her personal story with a broader view of Korean history. Through these pages, you are asked to experience one familys heartbreak, trauma, and complex love for each other. This memoir will pierce you.

CRYSTAL HANA KIM,

author of If You Leave Me

This memoir broke my heart. The tragedies that filled the lives of Kohs mother and grandmothers are woven into mythic, magic tales in Kohs hands. Only by Kohs grace and mastery are we not crushed by the stories within The Magical Language of Others. I could read this book a thousand times over.

SARAH BLAKE,

author of Naamah

E. J. Kohs The Magical Language of Others grapples with intergenerational loss and love between mothers and daughters across time, war, and immigration. Kohs painful journey is bridged by her mothers letters, which she translates, unfolding the language of mothering and tenderness. Koh remarkably and beautifully translates the language of mothers as the language of survivors.

DON MEE CHOI,

author of Hardly War

Indisputably brilliant. I read The Magical Language of Others in a single sittingall the while never wanting it to end. With a formally daring structure and finely distilled sentences, Koh creates a densely layered, lyrical exploration of the bonds between generations of daughters and mothers.

JEANNIE VANASCO,

author of Things We Didnt Talk About When I Was a Girl

E. J. Koh artfully wields both words and the spaces between them, and in the gaps between languages, generations, countries, and members of a family, she finds both bridges and achingly deep rifts. This is simultaneously a coming-of-age story, a family story, and a meditation on language and translation, with an emotional range to match: Koh movingly guides us through deep longing and loneliness towards forgiveness, understanding, and purposeful, tentative joy.

CAITLIN HORROCKS,

author of The Vexations

In The Magical Language of Others, E. J. Koh writes of the boundary between anonymity and naming, between absence and abandonment, between cruelty and safety for four generations of mothers and daughters, each speaking with an occupied heart and crossing narrative borders between Korea, Japan, and America. As a reader, you give yourself over to her narrative territory and the resetting of the borders of lineage, language, and lives lost.

SHAWN WONG,

author of Homebase and American Knees

The Magical Language of Others

The Magical Language of Others

A Memoir

E. J. Koh

CONTENTS

My mother opens her letters in Korean, Ahnyoung. This translates into Hi or Hello. I use both for the Korean greeting. Hi beams outward like the suns rays. The tone transports energy without expecting reciprocity. One may absorb Hi with a casual wave or respond with a smile. Hello boomerangs for a response. Over the phone, one says Hello to hear a voice calling through silence. Hello is an alteration of Hallo or Hollo from Old High German Hal or Hol, used to hail a ferryman. Hello comes as a question. Are you there? Hello fetches me across an expanse of water.

Eun Ji is the name she gave me. Eun, as in mercy and kindness, closer to mercy than kindness. Eun falls between blessing and blessed. Ji lands at wisdom and knowing. Ji resides with judiciousness more than intelligence. Eun Ji does not echo willfulness or innocence. It resonates with softness and sensibility. Angela is my Catholic name, after Saint Angela Merici, a holy messenger. My mother calls me Angela when she speaks formally. Angela is proper for its foreignnesspostured for the public. Eun Ji belongs to her. Angela, to everyone else. She calls my brother Chang Hyun, his Catholic name John, or your brother. For my father, your dad. For her, she is always Mommy.

Mommy addresses a child, who remains one in her letters. This becomes clear when she switches to third person. When you feel a little better, if you want to talk to Mommy again, call me. Her third person is, in part, her mothering.

Since my Korean was limited when I was a child, she uses kiddie diction. She stays mostly at a basic level. For advanced vocabulary, she transcribes the first definition in her English dictionary and notes it in parentheses in place of or next to the original vocabulary. Auntie must get jealous (envy) because I have my Eun Ji. Translating is problematic for her, but also a treat. The letters note, at times, the wrong English definition. In one, she means promise and next to promise, she writes confirm but misspells it as conform. She says, Promise (conform) and say it to yourself. Her error becomes a delight that cuts tension, or stalls grief. In another, she defines promotion as propaganda. She writes, I have to assert and promote myself (propaganda). Her language slips out of a perfect transcription and gives relief with its obfuscation and humor.

Words she writes in English or changes into Korean English are italicized in the book, such as last of my life and God is fair, you know. Japanese words she writes in Korean are romanized: Nani ga hoshii desu ka?

Korean phrases are a favorite. Aja, aja, fighting! Not a signpost that signals transition between parts, this translates into Lets go, lets go, fight! The phrase uses the English fight or fighting. Aja, aja is a sound of activity, quick-footed, rising from the gut. Together, they bolster fortitude.

Readers may ask whether I wrote her back. Her letters are a one-way correspondence. The thought of writing her was unbearable. Korean was a language far from me. I never suspected I would come to it in the end.

The letters are included in their original form and not all appear in chronological order. Some letters have dates for meetings that happened at different times.

To my limits, I do not see my translations as complete. If her letters could go to sleep, my translations would be their dreams. The letters transport my mother to wherever I reside, so they may, in her place, become a constant dispensation of love.

Forty-nine letters were discovered after an unknowable number had been trashed or forgotten. In Buddhist tradition, forty-nine is the number of days a soul wanders the earth for answers before the afterlife.

Dear Eun Ji.

Hello, hello, hello, my Eun Ji.

You said youre doing well? We phoned yesterday, remember? Mommy got a little angry, but not at you. Mommy didnt take good care of things and had thoughts like, Ive put you guys up in a very dirty place. If you lived with Mommy, you wouldnt raise a dog and Eun Ji wouldnt be alone at the house in Davis every day, right? Then, without asking, you guys bought a