Why didnt you and Daddy want people to give you any presents? I used to ask. But my mother could never be drawn into talking about the wedding. I assumed it was because she did not wish to be reminded of the ghastly mistake she had made in marrying my father.

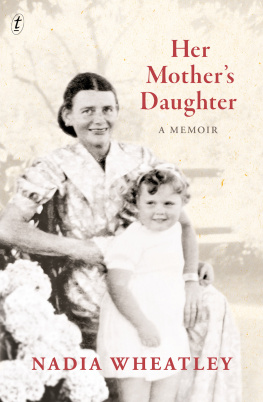

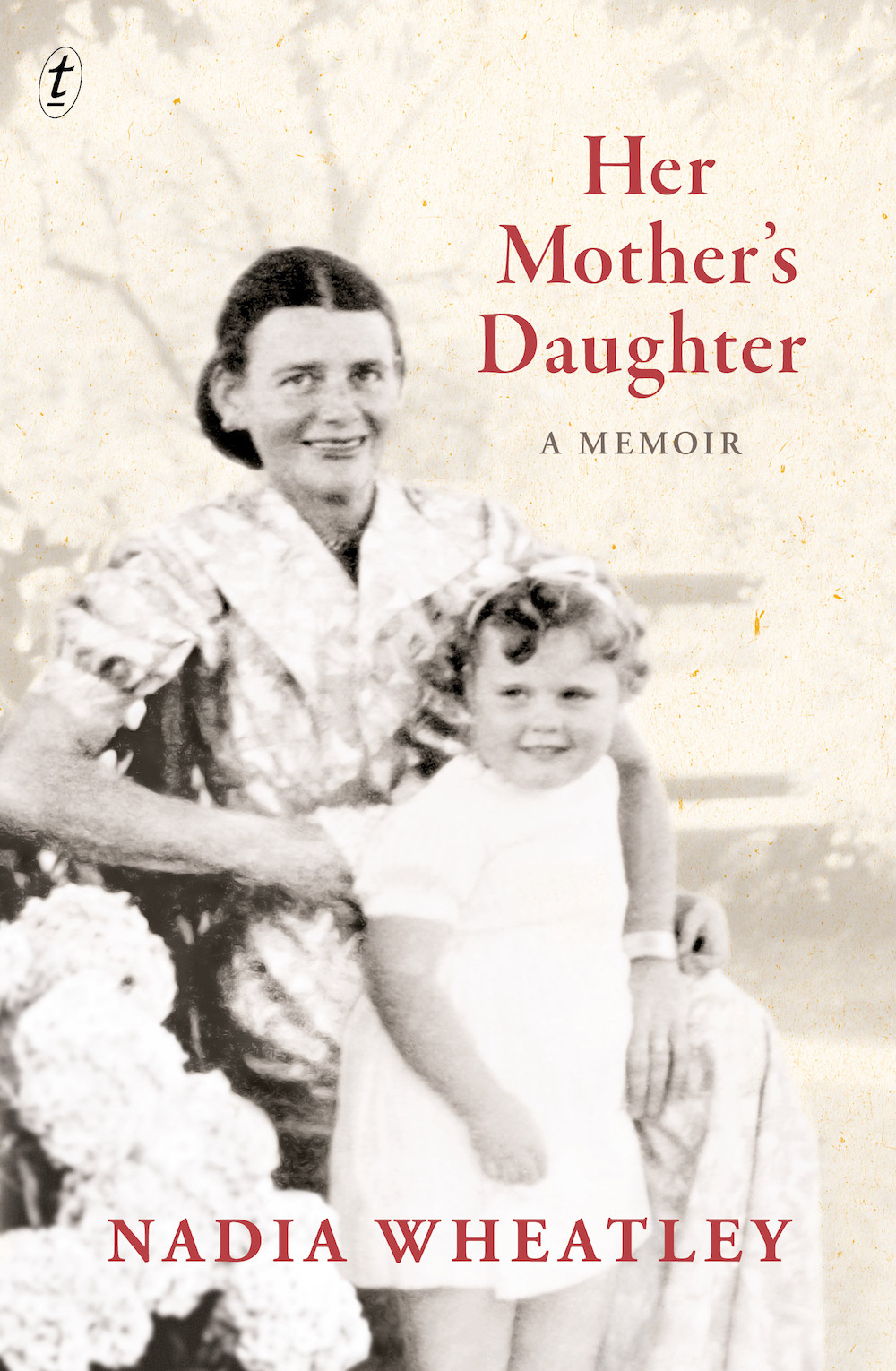

As a child, Nadia Wheatley had a sense of the great divide between her parents, who had met and married while working in Germany during the Cold War. Growing up in 1950s Australia, the child became a player in their deadly contest. Was she her mothers daughter, or her fathers creature?

At the age of ten, Nadia began writing down the stories of her mothers Cinderella-like childhood and her escape into a career as army nurse and refugee aid-worker. Fifty years later, the finished memoir is not only a loving tribute but also a social history of twentieth century Australia, told through the lives of a mother and her daughter.

i.m.

N.I.W.

3 / 4 / 1906 13 / 11 / 1958

Our concern with historyis a concern with preformed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered.

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz

Contents

Whenever I picture Neen, the first thing I see is her long black hair.

In a particular moment in memory it falls loose over her shoulders as we sit together on the back verandah of the farmhouse at Brooklyn, catching the morning sun that even in winter feels almost tropical in the sheltered north-coast valley that was my mothers birthplace. Neens mother, Isabella, had black hair too; according to family legend, she was so beautiful that all the men of the Upper Orara wanted to marry her.

But she chose Grandpa, I say proudly, and he built a house for her. And it seems extraordinary to me that it was the very same house where we are now staying for our holiday with Uncle Rolie and Auntie Doris.

By this time of the morning the cows have meandered from the bails back to the river flats, and in the deep silence that has fallen upon the farm now that milking has finished, Neen is sitting on the back step while I stand behind her, brushing her long, wet, black hair, which she has just washed in the chipped green enamel basin. When it is dry she will arrange it in her distinctive style: parted in the middle, then plaited into two braids that she coils and fastens behind her ears with hairpins that are always falling out, so that wherever she goes I can follow these traces of her. Since starting nursery school, I have come to see this hairstyle as one of the many things that sets Neen apart from other childrens mothers, who all wear their hair cut short and permed, in the fashion of the day. But while I love Neens plaited snails, as I call them, and I would never want her to change, I love her hair even more when she lets it fall free.

Why cant I look like you? I ask as I pull the brush down through hair so fine that it fizzes with electricity.

Because you are your fathers daughter, Neen replies, as if that is all there is to be said about the matter.

And it is true. I have Daddys blue eyes and his plump build and his English skin that burns bright red at the slightest touch of the Australian sun. I have never seen his hair, but I imagine it was fair like mine before he went bald. But it is my mother whom I want to be like, just as she was like her own mother.

Were you sad when you were a little girl and your mummy died?

Of course I was.

How old were you?

Whenever I ask Neen how old she is, she refuses to tell me, but now she says, as if it is the first time she has thought of it, When my mother died, I was not much older than you are now.

Does a ghost walk over my grave as Neen says this? The thought of her as a little girl, torn apart from her mother, makes the flesh on my arms go cold and goose-bumpy. But that could never happen to us, so within a moment or two, the motherless child has been transformed into a barefoot girl in a raggedy dress, standing in the snow, selling posies of violets, like the beggar-girl in the painting at Auntie Ednas house. The flower-sellers skin is white and her eyes are the darkest brown and her long black hair hangs all the way down to her waist. And then along comes a princess, and she buys all the violets, and she takes the little orphan girl home to live in her palace. Where it turns out that the princess is really the little girls mother, who isnt dead after all

There are two photographs, taken in a north-coast photography studio in about 1910.

In one, a little girl with black hair tied in bunches above her ears stands with her hands clasped beneath her chin, elbows resting on a small table on which a rose has been placed. Despite the winsome pose, the childs huge, dark eyes seem to blaze out at the viewer. Her mother, photographed on the same occasion, is a commanding figure in her black bombazine with its high neck and pin-tucked bodice. Her luxurious black hair is piled on top of her head, and she has the same dark eyes and white skin as her daughter.

But where did this colouring come from? Despite the names Isabella and Nina, there isnt any Spanish blood in the family, or not as far as I am aware. The silence that cloaks my grandmothers origins is no accident. Both Isabellas grandfathers and one of her great-grandfathers were transported to Australia as convicts, and her maternal great-grandmother, Ann Forbes, travelled to Botany Bay as a fifteen-year-old convict aboard the First Fleet. This type of ancestrynowadays so fashionablewas still unmentionable during the era of my mothers childhood, so Neen grew up knowing little of her maternal history. Nevertheless, it was from the women of this side of the family that she got her distinctive looks, and also perhaps her restless spirit.

Fiercely independent, the convict lass Ann Forbes did not take the easy course of becoming an officers whore, but settled down with a fellow convict on a bend of the Hawkesbury River they named Paradise Point. Her female descendants showed the same survival instinct, pushing their husbands and sons into a migration that took their families ever northwards, in search of the red gold of the cedar forests and better agricultural land. By 1867, one branch of Anns descendants had established themselves around the small township of Millfield, in the Hunter district. It was there that Isabella Parry was born.

One of the first generation in her family to go to school, Isabella loved the atmosphere of the classroom so much that she longed to be a schoolmistress when she grew up. Her timing was perfect. In 1880 the state system of education was inaugurated in New South Wales; soon little schools were popping up throughout the bush, each one needing a teacher. For thirteen-year-old Isabella Parry, who finished school that year, there was no gap between being a pupil and becoming a teacher. Over the next decade, she worked in a string of tiny settlements along the Clarence River, where her extended family was putting down roots. A photograph taken at Calliope, north-east of Grafton, in 1893, shows Miss Parry clad in a stiff black dress, standing outside a weatherboard schoolhouse with her class of eleven boys and fourteen girls, some as tall as their teacher.

Meanwhile, Isabellas two sisters and their husbands had moved to the newly settled district of the Orara River. By the early 1890s, there were enough children in the valley of the Upper Orara for the parents to get together and build their own schoolhouse. Now all they needed was a teacher! In June 1895, Isabella moved to her sister Ross place, near the little township of Coramba, from where she was able to drive the sulky each day to the one-room school on Karangi Creek. As a sign of her vision for its future, Miss Parry planted a camphor laurel tree beside the gate.