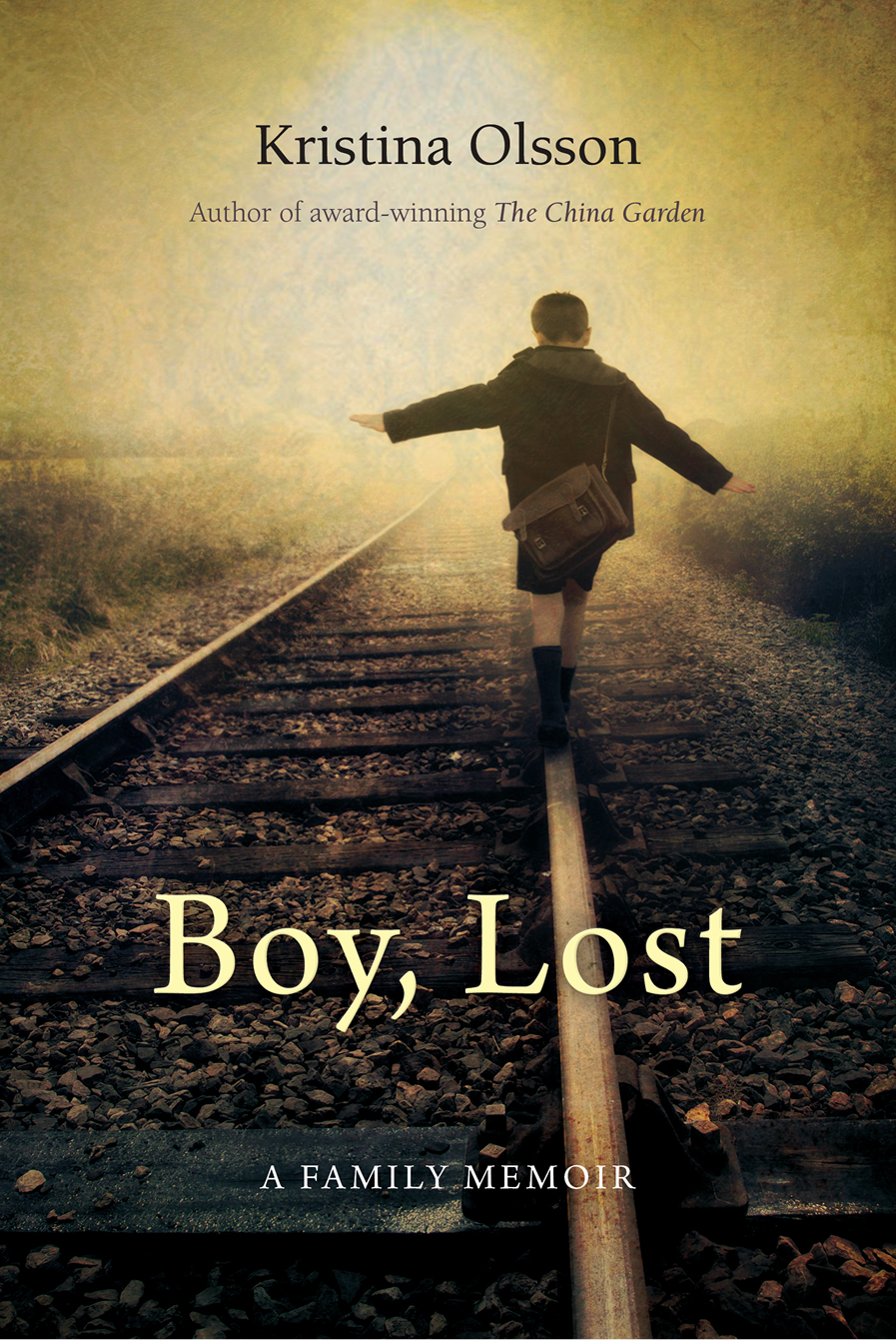

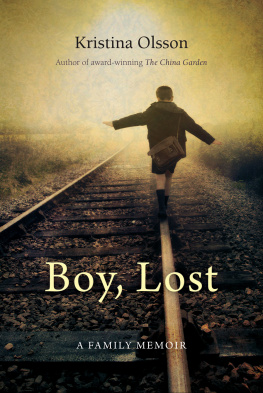

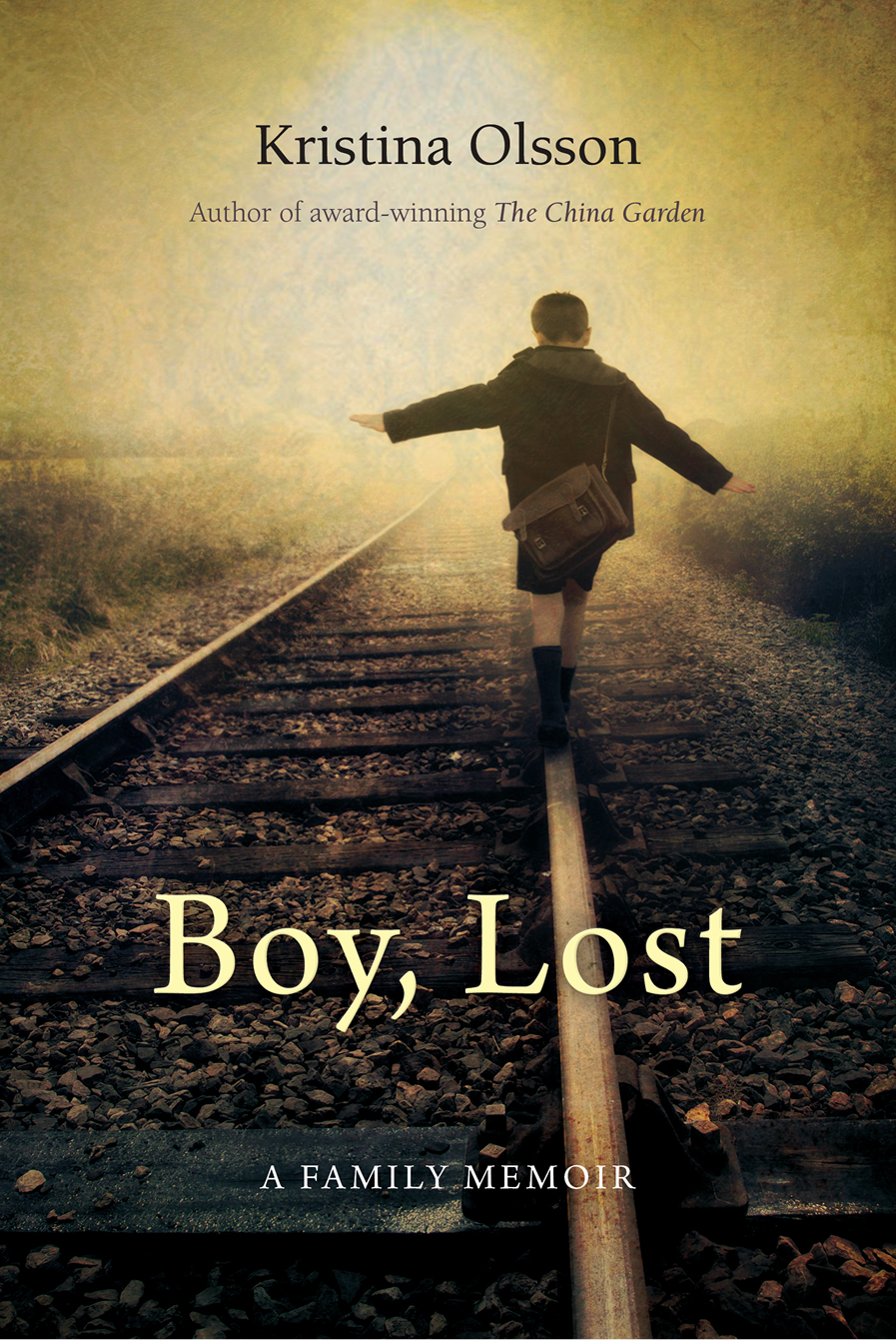

Kristina Olsson is the author of the novel In One Skin (2001) and the biography Kilroy Was Here (2005). Her second novel, The China Garden (2009), received the 2010 Barbara Jefferis Award for its empowering depiction of women in society and was also shortlisted for the Kibble Literary Award. Kristinas journalism and non-fiction have been published in The Australian, The Courier-Mail, The Sunday Telegraph and Griffith Review. She has worked extensively as a teacher of creative writing and journalism at tertiary level and in the community, and as an advisor to government. She lives in Brisbane.

Kristina Olsson is the author of the novel In One Skin (2001) and the biography Kilroy Was Here (2005). Her second novel, The China Garden (2009), received the 2010 Barbara Jefferis Award for its empowering depiction of women in society and was also shortlisted for the Kibble Literary Award. Kristinas journalism and non-fiction have been published in The Australian, The Courier-Mail, The Sunday Telegraph and Griffith Review. She has worked extensively as a teacher of creative writing and journalism at tertiary level and in the community, and as an advisor to government. She lives in Brisbane.

Also by Kristina Olsson

Fiction

In One Skin

The China Garden

Non-fiction

Kilroy Was Here

For my mother and Peter

For my father and Sharon

For Lennart, Ashley and Andrew

Cairns railway station, far north Queensland, summer, 1950. A girl with fugitive eyes and an infant on her hip. She is thin, gaunt even, but still it is easy to see these two are a pair, dark-haired and dark-eyed. She hurries down the platform towards the second-class cars, slowed by the weight of her son and her cardboard suitcase. It holds everything they own, everything she dared to take.

She finds a seat in one of the last cars perhaps it feels safe, perhaps she is already getting as far from this place as she can and settles herself. She has some food wrapped in paper, a dry sandwich, arrowroot biscuits there was nothing else in the flat. Peter that is the boys name is tired, fractious, out of routine. Somewhere in her own weary brain she knows he is echoing her, responding to her own fear, her own curdled mix of terror and sorrow and the adrenalin it has taken to get her here. She talks to him quietly, she hopes he wont cry. She doesnt want anyone to hear him.

This is the scene as I see it, sixty years later. It is sepia-toned, like the photographs I have of her then. Nineteen years old, with a face people compared to the young Elizabeth Taylor, and fine-boned limbs. But the fineness apparent through her thin shift that day had nothing to do with her natural build. She was malnourished, starving. Later, when she stumbles off the train in Brisbane she will be taken away to hospital. No one will know until then no one could tell that the new pregnancy shed protected and kept secret was now well advanced.

But that is days later. Whole days and a lifetime from the minutes she waited on the train, willing it to move, to take them to safety. A lifetime because surely that is how long the journey seemed, how long shell have, later, to recall over and over a single moment. The man appears at the door of the carriage, walks towards her a twisted smile and roughly pulls Peter from her arms. Later, in memory and dream and conversation, she will wonder what else he said to her, apart from those few chilling words. Dont move the Greek accent was heavy and cruel; the baby whimpered, reached for his mother, a biscuit in his fist Dont move, you bitch. Stay on the train or youre dead. Him too. She knew from the brutality of the past months that he meant it.

He waited then, his bulk blocking the doorway, until a whistle blew and the train shuddered. Did she plead with him in those minutes, beg, tell him shed stay? Did she try to strike a bargain, some pathetic deal? I doubt it. In the parlance of the poker games he was addicted to, she had nothing to bargain with, no cards to play. She had only herself, her own bruised and flimsy body, her poor bullied heart. He didnt want her.

This is the story my mother never told, not to us, the children who would grow up around it in the way that skin grows over a scratch. So we conjured it, guessed it from glances, from echoes, from phrases that snap in the air like a birds wing, and are gone. Fragments of a legend, thats how it seemed, and it twisted through our childhood like a fiction we had read and half-forgotten; a story that belonged to others, not to us, and to another, long-ago time. As if the woman at its centre was not really our mother but a stranger, an unknowable version of her, not the woman who made our school lunches, plastered our cuts, grimaced daily over the washing tub and wringer. Smiled as we came in the door.

We knew questions were off-limits. The story had its own force-field, our mothers sadness as effective as any electric fence. So we learned to live alongside it, or rather, beneath it, conceding to its terms as we conceded to anaesthetic for our various childhood maladies tonsils, ears, teeth. Learned not to notice not consciously the fierceness of her compensations: the pull and push of need, the nearness and distance of love. We learned, as children do, to behave in ways that might make her, if not happy, then less unhappy. We were still doing this when she died, too young, twelve years ago, and in some ways we havent stopped.

In the years before wed learned some of the facts the earl ier marriage, the cruel husband, the stolen baby but the flesh and bones of her life were buried with her in autumn-damp soil. What she left was a fine, opaque pattern like the ones she pinned over fabric to make our clothes, a movable outline that refused to be fixed. We began to ask questions then, wanting the answers shed never have given. But our knowledge was partial so our questions were too; with every answer the lines shifted, and with them the shape of her.

This is what we didnt understand, not then: that the past had gripped and confounded her, stalked her dreams. That every day of her life after her son was taken, she would sift through the memory of it, every terrible second. Turning each in her hand, looking for ways she might have changed them. But always she would be stuck at the image of the man, her husband, the terrible smile as he entered the train carriage, walked towards her, pulled Peter from her arms. When she dreamed of her lost son she would dream of his father. He would always be walking towards her, wearing that smile.

In my head, it happens like this: she is standing behind the high glass counter of The Palms Caf in Queen Street. It is lunchtime and busy, but she is momentarily still, flicking at a drift of flour on her apron or perhaps she is tucking back a lick of wayward hair and checking her lipstick quickly, covertly in the mirrored panel behind her. At sixteen she has the celebrated curves of a movie star, 36-24-36, and is told she is just as beautiful. Of course, she doesnt believe it though shed like to. She doesnt want people to think she is vain. Her father, especially. Hed be disappointed, she knows, at any sign of vanity, any sign of conceit.

As she leans into the mirror she touches a forefinger to her lips they are full, crimson-tinted and sees suddenly she is being watched. It is the same man, the same eyes she had felt on her earlier that week as she carried trays with cups and teapots and scones between tables. He is darkly good-looking, and well dressed pressed trousers, a starched white shirt. He is not a boy. A smile lurks at the corners of his mouth and it is the smile of a worldly man. A smile of intent. Her stomach flips like a fish on a hook.

Her hands move once more to her apron, she smooths imaginary creases, then turns to the serving bay. She has to remind herself to breathe. But there is safety in the plates of piled food; she risks a glance from lowered eyes. This is what she sees: his dark beauty. That it has made him dangerous. His eyes. Charisma and the possibility not just of vanity but of toughness. Of passion. She sees all this now, but seeing is not knowing. Otherwise, why would she risk that glance, a faint movement of her eyes and lips, a telltale dip of long lashes? She slides plates onto a nearby table and as she spins away he appraises her legs, her fine ankles.

Next page

Kristina Olsson is the author of the novel In One Skin (2001) and the biography Kilroy Was Here (2005). Her second novel, The China Garden (2009), received the 2010 Barbara Jefferis Award for its empowering depiction of women in society and was also shortlisted for the Kibble Literary Award. Kristinas journalism and non-fiction have been published in The Australian, The Courier-Mail, The Sunday Telegraph and Griffith Review. She has worked extensively as a teacher of creative writing and journalism at tertiary level and in the community, and as an advisor to government. She lives in Brisbane.

Kristina Olsson is the author of the novel In One Skin (2001) and the biography Kilroy Was Here (2005). Her second novel, The China Garden (2009), received the 2010 Barbara Jefferis Award for its empowering depiction of women in society and was also shortlisted for the Kibble Literary Award. Kristinas journalism and non-fiction have been published in The Australian, The Courier-Mail, The Sunday Telegraph and Griffith Review. She has worked extensively as a teacher of creative writing and journalism at tertiary level and in the community, and as an advisor to government. She lives in Brisbane.