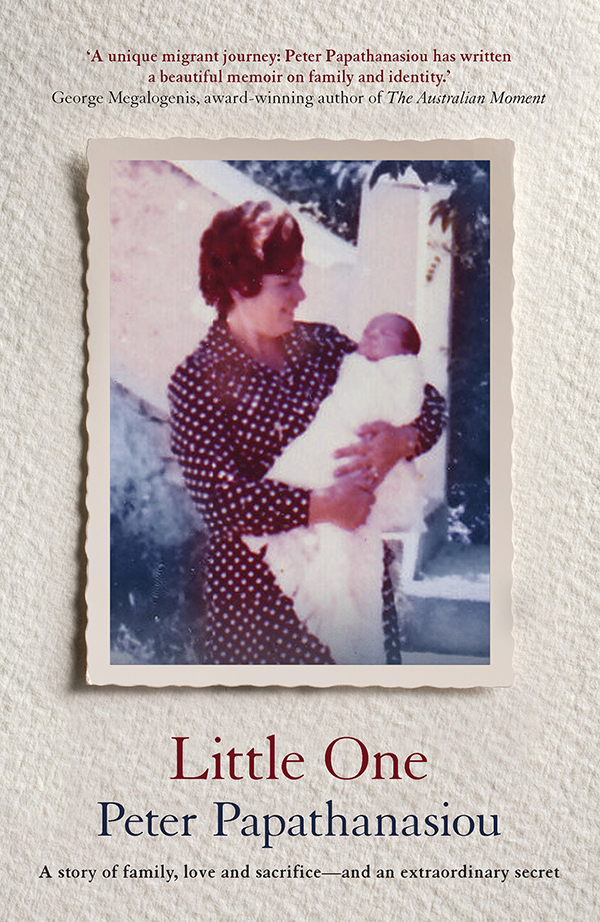

First published in 2019

Copyright Peter Papathanasiou 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 559 6

eISBN 978 1 76087 139 0

Internal photographs courtesy of the authors collection

Set by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Cover images: Savvas Paraskevaidis (photograph of Elizabeth and Peter Papathanasiou); iStockphoto (background)

For my parents, all four of them

You were once a newborn. Its probably hard to imagine that now, sitting comfortably in your seat, wearing your clothes and reading this sentence. But there was a time when you were naked and new, bloody and blind, crying and cold. You were conscious in that moment, but will never remember it. You emerged from your mothers exhausted body in a moment. The cord was clamped and cut. The events that preceded it, and those that immediately followed, were beyond your control

1999

It was the hottest day of summer, a Saturday in January. I sat cross-legged in my study, surrounded by piles of undergraduate textbooks, flicking through them, leaving light fingerprints of sweat on the pages. Having studied science and law for six years at university, I was about to embark on a PhD in genetics, and so was packing my old textbooks away. Seeing myself on each meticulously highlighted page, I sighed lightly, remembering all the time Id spent understanding, memorising, and ultimately regurgitating those passages in cold, cavernous exam halls. The focus was now going to be on experiments not exams, data not grades, discovery not curriculum. Occasionally I stopped to read an extract, which brought back even more memories of lectures, lecturers, tutorials and classmates. It was a job well done, graduation with honours, but all behind me now.

Mum looked into my room again. She had something on her mind. She hoped I wouldnt notice but it was impossible not toshe had poked her head in umpteen times that day. Having lived with my parents my whole life, I could tell when they were genuinely busy and when they were hovering. The phrase helicopter parenting could very well have been coined for them, and especially for Mum. I knew she loved me, but at times it was to the point of suffocating her only child.

Mama, I said, whats up?

Mum stopped, leaned against the door frame. She didnt respond for some time. Eh, she finally said, nothing.

You keep walking past my door. A dozen times now. Its not nothing.

She rubbed her hands together pensively. Eventually, she asked: Are you busy?

I returned to flicking pages. Matters of world importance, I replied.

Mum was silent. Failing to sense my sarcasm, she continued to stare at me. After a few moments, I looked back up and met her gaze. It was as if she were assessing me, sizing me up for something. As she gazed longer and deeper into my eyes than I thought anyone ever could, I felt lightheaded. There were generations in that look. Mums stature was small, and her hands tiny, with purple veins protruding, her fingers beginning to turn in with arthritis. But at that moment, she appeared like a giant.

Slowly, almost cautiously, I closed my book. Mama I said, ela, what is it?

Finally, she spoke: Can you come to my room. Ive something to tell you.

My stomach tightened.

As I followed Mum down the carpeted hall, a memory cut across my brain. The last time she had insisted we talk in her room was during my first year of university. My aunt in Greece had died suddenly.

Mum closed the door behind us. Her bedroom smelled of fresh linen. I didnt exactly know where Dad wasprobably out the back in his shed or at the betting shopbut knew he wasnt in the house. The large, north-facing window amplified the hot summer sun like a magnifying glass.

Please, Panagiotis, sit down.

Mum always called me by my Greek name during moments of significance. It had been there in hospital during emergencies, in church during baptisms and funerals, and at home during lectures for teenage misbehaviour. I didnt mind it, but I knew what it meant. Someone had died, or was dying.

Ill stand, Mum. Please, what is it?

Mum took up position on the edge of the bed, her bare feet resting on a thick blue rug. Looking down at her hands, she began.

When I was young, I tried many times to get pregnant. Although your dad and I succeeded three times, I miscarried each time. Three. She held up three bony fingers. One, two, three babies I carried but never met. Even after all this time, those memories are with me, every day of every week.

I listened, silently.

Your baba and I wanted so much to have a family, we were losing our minds. Those werent easy days. Wed been through a lot, coming all the way out to Australia after the war. In the end, the time came when we thought we had no other choice. We had to consider the option of taking someone elses child.

Mums eyes suddenly welled up and her face went red. She took a deep breath. Uncertain of what was to come, I did the same.

Now there were places in Greece where you could adopt babies who werent wanted. But you needed to meet certain standards, have money and status. And your dad and I didnt. So in the end, my brother Savvas and his wife Anna proposed to have a baby for us. They already had two sons who were almost teenagers, so their child-rearing days were well and truly behind them. But they were willing to help your baba and me. I felt terrible about my brothers wife having to carry and give birth to another baby for me, her non-blood relative. But our lives here were childless and, well, meaningless. In the end, an arrangement was made. Anna fell pregnant, and I flew to Greece.

A tear rolled down Mums left cheek. She pulled a folded tissue from her pocket and wiped her eyes. She fought hard to compose herself and not lose her place in the story.

Your dad worked here while I was in Greece, and sent money when he could. During that time, I completed all the paperwork that was needed to bring you back to Australia. Six months later, we flew back. From that day, you havent set foot in your country of birth, and the only contact with your birth mother was when she and I talked on the phone. To you, she was simply your aunt. And to her, too, this was the case. Even though she loved you dearly, it was for us to raise you in the way we chose. You became our child. She saw the benefits of life here, and it was why your dad and I came out in the first place. Your brothers, the two boys whom Ive always said were your cousins, know everything youve been doing all these years.

Brothers

I put my fingertips to my temples, as if to steady myself, and let the new word nestle inside my brain. Brothers were such an unfamiliar concept. They had always been something the other kids in school had as I was growing up, in higher grades who protected them, or in lower grades whom they beat up.