The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Foreword

D URING more than a decade as royal correspondent for the BBC I have waged many a battle with Buckingham Palace over access to information. I have berated and badgered a succession of press secretaries, demanding answers to my questions. Slowly and grudgingly the Palace doors have opened enough to allow a chink of light inside. The process has been given the odd unexpected boost by one or two members of the Royal Family whove volunteered to go public with astonishing personal revelations. There remains, however, a deep scepticism within the Palace walls about the media and their function in reporting on royalty. Greater still is the horror with which any member of staff who spills the beans is viewed.

Patrick Jephson, who gave his account of life as private secretary to the Princess of Wales, was seen as a traitor to her memory. Wendy Berry, a former housekeeper at Highgrove, was forced to flee to Canada when she published a book that was described to me by someone in the household as the most accurate record of the final years of the Waless marriage. But the pioneer of the royal kiss and tell was undoubtedly Marion Crawford, governess and confidante of Lilibet, the young girl who would one day become Queen, and of her sister Margaret.

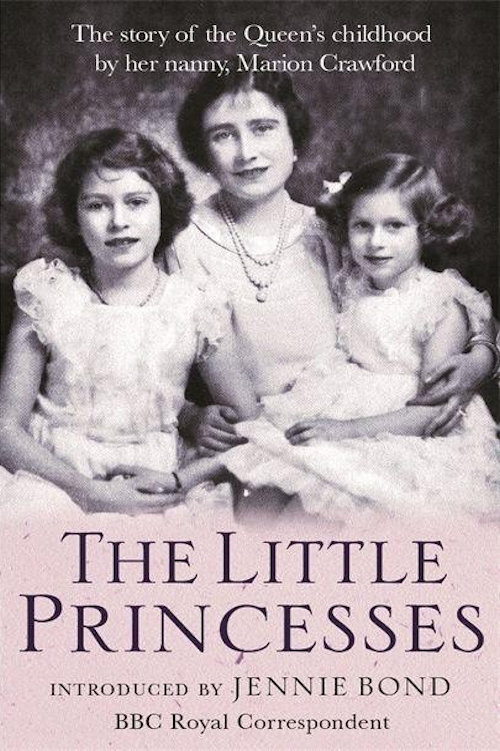

The Little Princesses is a charming, hopelessly romantic chronicle of Crawfies life during sixteen years at the heart of the Royal Family. It is also a valuable piece of social history, detailing every aspect of Elizabeth and Margarets childhood through the crucial years of the Abdication and the war as well as Lilibets courtship and marriage.

It is harmless in the extreme: among the most explosive revelations is the fact that in the schoolroom the two Princesses behaved like entirely normal and healthy little girls. Neither was above taking a whack at her adversary, if roused, and Lilibet was quick with her left hook!

But the publication of the book led Queen Elizabeth later Queen Mother to conclude that Crawfie had gone off her head. She was cast adrift as if she had committed treason and neither the Queen nor the two Princesses ever spoke to her again. Her only crime had been to paint an affectionate and loyal portrait of a family to whom she had devoted a large part of her life at considerable personal cost. But it was a crime for which she would never be forgiven.

Marion Crawfords own childhood had been a far cry from the world of palaces and castles that was to become so familiar. Born in a cottage near Kilmarnock in 1909, her father died when she was one year old. When her mother re-married, the family moved to Dunfermline, where Marion was educated. She always felt she had a vocation to teach, and imagined she would end up helping some of the poor and undernourished children she met during her training in Edinburgh. But fate intervened. No sooner was she qualified, than a network of acquaintances led her to the Duchess of York and a plum job in the royal household. It was a bold step by the Duke and Duchess to employ someone as untested as Marion Crawford; not only was she inexperienced as a governess, she was also very young at just twenty-four she was nine years the Duchesss junior. But this was part of her appeal; the Duke had unhappy memories of his elderly tutors and was determined that his girls should have someone with more energy.

Crawfie, as she was soon christened by her charges, found that her job description was fairly nebulous. Apart from running around with them, her chief instruction appears to have come from the childrens grandfather, King George V, who appealed to her to teach Margaret and Lilibet to write a decent hand, thats all I ask you. Not one of my children can write properly.

Those who knew her say Crawfie was a shy Scots girl, always extremely pleasant without being particularly interesting. No one questions her devotion to her two young charges, and the Princesses were equally devoted to her. Here, at last, was someone willing to join in their games.

The book paints an intimate portrait of life in the nursery: One of Lilibets favourite games that went on for years was to harness me with a pair of red reins that had bells on them and off we would go, delivering groceries.

It seems unsurprising that Lilibet who in adult life is viewed as pretty buttoned up was an extremely tidy child. Crawfie was struck by the immaculate condition of her thirty toy horses, each with its own saddle and bridle carefully polished by the girls themselves. At times the tidiness appeared to border on obsession, with Lilibet getting out of bed several times a night to check that her shoes were neatly lined up. It is with some relief that we learn that this serious child could have moments of rebellion as she did during a desperately boring French lesson when she seized a silver inkpot and turned it upside down on her head. A predicament from which Crawfie had to rescue both the Princess and her French teacher.

Margaret, meanwhile, is portrayed as wilful and headstrong spoiled by her parents but with a quick, bright mind. You get the impression that she was quite a handful for Crawfie, but that her sometimes outrageous behaviour was refreshing in the confined world in which they all lived.

There are so many things Margaret could have done with brilliance and distinction, she writes. According to Crawfie, Lilibet was protective, even motherly, towards her younger sister.

In her own intuitive fashion I think she saw ahead how later on Margaret was bound to be misrepresented and misunderstood.

She did not, however, foresee that her own governess would become the Palace ogre who sold the familys secrets. Crawfie certainly gave no hint that she was intending to sell her story. Indeed, there is a piquant irony in the book as she recounts Lilibets unhappiness about the publicity surrounding her engagement to Philip.

The heart of a Princess is shy and as easily hurt as any other young girls heart, writes Crawfie. In time royalty grow accustomed and hardened to this prying into their private lives and make little of it. But not at nineteen. Not in love, deeply and passionately, for the first time.

She concludes that royalty earn every penny they get for their loss of privacy.

So why, then, did Marion Crawford so well-liked in royal circles, trusted by her employers and adored by the Princesses decide to compromise that privacy, however sycophantically?

Several theories have been put forward, but the truth may never be known. One school of thought argues that Crawfie was seeking revenge because she was only made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order when she left the royal household, instead of the grander Dame Commander.

There is, though, nothing that smacks of vengeance in this sympathetic and uncritical book. Another theory, unearthed in a television documentary fifty years after The Little Princesses was published, is more Machiavellian. It claims that Crawfie was the scapegoat for a botched PR campaign hatched by the Foreign Office and Queen Elizabeth (now Queen Mother) designed to improve the Royal Familys standing in the United States. According to this theory, the view was taken that a series of well-sourced articles in a top American magazine would do the Royal Family a power of good. Crawfie was allegedly told she could co-operate, as long as her name wasnt mentioned; but she failed to read the small print of the contract which allowed her to be named as the author.

![Chris Crawford [Chris Crawford] - Chris Crawford on Game Design](/uploads/posts/book/119438/thumbs/chris-crawford-chris-crawford-chris-crawford-on.jpg)