The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my mom and dad,

who gave me both a love of writing and love of racing,

and my wife, EJ, the love of my life.

In memory of my grandson Matthew,

who taught me to make every day count.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

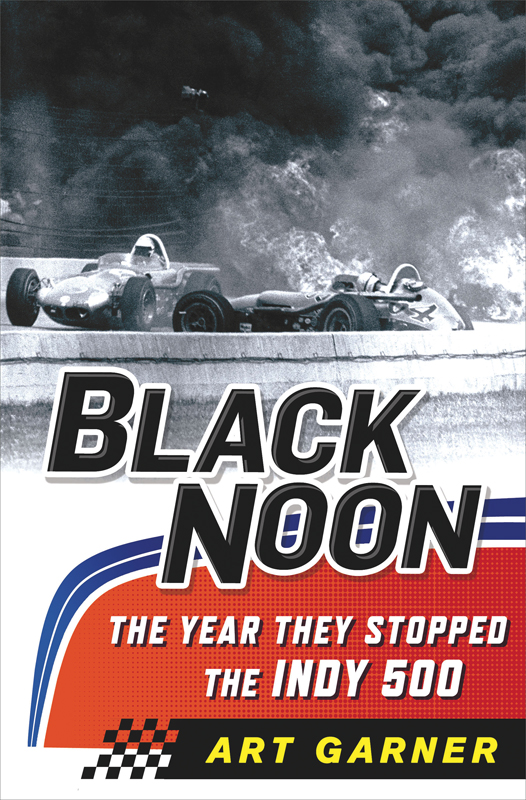

As the start of the Indy 500 approached on May 30, 1964, a record crowd of about 275,000 jammed into every nook and cranny of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Every seat was sold, and people packed twenty-five deep along the infield fences, hoping to catch a glimpse of the cars as they sped past at more than 150 miles per hour. Another 250,000 people crowded into sports arenas and movie theaters across the county for the first live broadcast of the race, and 100 million more were tuning in to the radio broadcast around the world. The biggest crowd ever for a sports event buzzed with anticipation.

* * *

Black Noon: The Year They Stopped the Indy 500 is a story about the events and circumstances surrounding the 1964 Indianapolis 500. It reaches a zenith in a fiery inferno that stops the 500 because of an accident for the first time in race history and turns a vivid blue Indiana sky black with billowing clouds of death and destruction. It remains the only accident to claim the lives of two drivers in Indy 500 history.

It is a story of the end of an era and the beginning of a new one, a story of a dying breed of men and machinery. It is a story of a time when drivers figured they had a 50/50 chance of being killed in a race car and worked odd jobs during the off-season for a chance to defy those odds.

It is a story of defiance and desperation, of courage and determination, of record speeds, record crowds, and a record purse. It is a story of fateful decisions resulting in unanticipated conclusions.

It is a story of great innovation and technological advancements: the front-engine roadster, the dinosaur, facing the new rear-engine funny cars; the vulnerable Offenhauser engine, winner of its first race in 1935 and every 500 since World War II, facing the latest technology from Detroit.

It is a story involving some of the great names in racing history, including A. J. Foyt, Jimmy Clark, Parnelli Jones, Dan Gurney, Bobby Unser, and Johnny Rutherford.

Most of all, it is the story of the two men who died in the crash, Eddie Sachs and Dave MacDonald. Two men from very different backgrounds, very different lifestyles, and with very different stories to tell.

It is a story about Sachs, a product of the blue-collar South and Midwest, who called home such places as Greensboro, North Carolina; Allentown, Pennsylvania; and Detroit, Michigan. A college dropout, he spent years developing his limited natural skills on the countrys short oval tracks before finally heading to Indianapolis. He was the first driver ever to fail his rookie test twice. Yet once he finally qualified for the race, he was always one of the leaders and came within three laps of winning in 1961. He was a fan favorite, known as the Clown Prince of Racing. A reformed playboy who had settled down with his second wife and newborn son, Sachs was making inroads in the business world and promised his family to retire from racingas soon as he won the 500.

It is a story about MacDonald, a rookie at Indianapolis, making his very first start in an Indianapolis-type race car. Yet he sailed through his test. Called the Natural by some, hed risen from weekend Southern California drag racer to national champion road racer in just four years. Blessed with surfer-boy good looks, off the track MacDonald was the quiet father of two young children, introverted, almost timid, according to friends. On the track, MacDonalds aggressive driving style attracted a legion of fans. He was coming off the best racing year of his career in 1963, ending the season not only in victory and with a championship, but by lapping a field of the worlds very best drivers.

It is a story of a different era, when drivers lived hard, raced hard, and often died hard. When drivers vied to post the fastest time of the day at Indy in order to win the free dinner that went with it. When entire race teams slept on cots in the rented garage of a nearby home. When safety was often an afterthought and drivers had what Gurney called a World War II mentality.

Much has been written about the Golden Age of Indy car racing, generally considered to start in 1965. Little has been written about the sports blackest day that ultimately gave birth to the Golden Age. This is that story.

* * *

In writing Black Noon, I had an opportunity to speak at length with six of the seven surviving drivers from the race including Foyt, Gurney, Bob Harkey, Jones, Rutherford, and Unserall but Jack Brabham, who lives in his native Australia. Mario Andretti, who considered taking his first laps at Indianapolis in 64 in a car from MacDonalds team but ultimately decided against it, talked about the decision and what it was like watching the race from the stands. I spoke with relatives of MacDonald and Sachs and of Ronnie Duman, who survived the 64 crash only to be killed in another racing accident several years later. I talked with crew members. I had an opportunity to visit with eighty-eight-year-old A. J. Watson, tagged the Wizard of Indy by Sports Illustrated, in the same home near the track where hes spent the month of May every year since the 50s. I interviewed reporters and others involved in the race, and spectators who were sitting near the accident site and sit in those same seats today. More than seventy-five interviews were conducted. Many spoke emotionally about the race, and some said theyd rather not discuss it at all.

I spent weeks in Indianapolis-area libraries going through newspapers, magazines, and other records from the race. The city was blessed with three major daily newspapers in 1964, and competition for Speedway coverage was fierce; the papers often put out special editions each evening following the end of practice at the track, with the front page devoted to the days racing activities. I scoured the Internet and its many auto racing forums and chat rooms that occasionally cover the subject, providing a great deal of speculation and what if scenarios.

Obviously, after nearly fifty years, memories vary and blur. Some people recalled seemingly trivial activities while being unable to remember major events. For the most part, the drivers had the best recall, often telling their stories in the hardened, matter-of-fact fashion of someone who watched friends and competitors die in their chosen profession. Not surprisingly, drivers in the heat of the moment and traveling at speeds of more than 150 mph often viewed situations differently from others who may have been just a few feet away on the trackand from what may have been caught on film. When discrepancies did arise, I based my ultimate decision on what to include on all the facts available to me.

To best tell the story in a day-by-day, real-time narrative, Ive combined quotes and information from newspaper stories of the day with those obtained during my interviews, from driver biographies, and from other racing histories. Ive also pieced together quotes from stories by different reporters who were obviously part of the same interview session. In an age where reporters were forced to rely on pen-and-paper and shorthand for their notes, rather than tape recorders, these quotes varied slightly from paper to paper. The narrative has been kept in the proper context, however, with retrospective comments saved for the concluding chapter.