Afterword

Its Entertainment

Sua enique voluptas

(everyone has his pleasures)

Lest it be forgotten, attractions other than car racing have transpired over ninety-six years at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Babies have been conceived and born, people have keeled over with coronaries, balloons have ascended, privies overturned, ordinary folks busted and booked in the tracks infield slammer, bright-eyed kids have mortgaged their souls to the military, yelping dogs discovered sanctuary, golf tournaments waged, nude spectators stormed the track, flea markets pitched their tents, lunatics smuggled their street cars on the speedway and killed themselves, biplanes landed and took wing, tornadoes unleashed their dark vortices, conflagrations erupted, human ashes spread, trainloads of track dogs consumed, and rivers of beer gulped and pissed into oblivion.

Sound like fun? Evidently, some people think so. Why 425,000 or so Indy customers devotedly shoehorned into the IMSs 224 infield acres for one May day in 2002 nevertheless remains among the worlds major unsolved mysteries, ranking right up there with the identity of the Dinnertime Bandit. No less than His Excellency, Andy Granatelli the high priest of petroleum enhancers and an enigma in his own right, was at something of a loss to characterize Indy, if not to explain it. Andy articulately identified it, however, as a Memorial Day set piece of the purest Americana, rightly averring that Indy is corn. It is fried chicken and beer and box lunches and old racing friends and enemies.... It is the blare of bands. The only place in the country where Back Home Again in Indiana gets top billing over The Star Spangled Banner. Indy, he continued, is a special brand of hypnotism, and it sets up an impossible dream... I love it; I hate it.

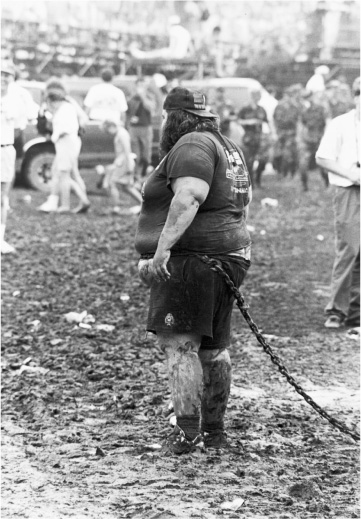

This sportsman eagerly awaits the onset of the 1991 500-mile race at Indianapolis. He appears to have been chained to his post. John Mahoney

No question. Its all an exercise in diabolic pop psychology. Pageant planners eventually figured out that a few folks of more or less sound mind viewed auto racing, all 500 miles of it, as monotonous, loud, point-lessly violent, and (above all) confusing. Dave Walsh, sports editor of the International News Service, opined in the 1920s that although you dont have to be crazy to drive a race car, it helps. Three generations later, eccentric, bow-tied publicity man Gaylord Snappy Ford retorted that racers were not half as nuts as some spectators. Be that as it may, some still see car racing as patently insufficient as nourishing sustenance for soul and spirit. Not everyone is there to view an auto race. The occasion cries out for more old fashioned midwestern wizz and vinegar, something to gussy up an auto racing marathon, to wit: a cathartic squadron of chocolate soldiers, cadenced drummers, tubas, pennywhistles, cymbals, motorcycle stunt riders, bozos who refuse to sit down, stirring marches, wafting balloons, billowing flags, cannonballs, drum and bugle processions, sailors, marines, boy scouts, tinhorn politicians, kilted bagpipers, apocalyptic preachers, television trash, aerial explosions, half-naked girls, honking horns, drunks, rhinestone cowboys, free-falling parachutists, solemn encomiums, deafening aircraft flyovers, barking dogs, and in 2001, a rappel demonstration, meaning, as nearly as we can determine, a person sliding down a rope.

Collectively they elevate the spirit and arouse, ignite, and invigorate even the deadest of souls. Driver Edward Julius Sachs, be he genius or fool, mystic or nimble-witted jester, was so impossibly overwhelmed by Indys race day arousal that in a moment of abandon he commandeered a drum majors baton, and with Sachsian aplomb strutted smartly uptrack with a full marching band close at his heels. Sachsie, never one to mask his emotions, unabashedly admitted that he never survived a pace lap without unbridled, epiphanous tears of joyous fulfillment coursing down his face.

There are a few, an anonymous scribe said of Indianapolis 500 grandstanders, who look upon the contest as a scientist might watch the antics of a medicated guinea pig. Even before there was a 500-mile race, one observer referred to auto races at the Speedway as a three-day racing carnival. It was not until 1923, however, that the Speedway devoted any attention in its race-day program to hyping its burgeoning appetite for sideshow entertainment. That was the year it trotted out an in-your-face 1,500-piece band composed of fifty smaller musical units prepared to uncouple and meander through the crowd at whim and will like wandering minstrels, regaling any who might bend an ear. College, Industrial, Fraternal, Civic, Soldier, Municipal, and even High School bands, a program notice read, gather for this enormous tournament of music. Led by a color guard of United States Marines the band parade is one of the most stirring, patriotic and commemorating scenes that will be held anyplace in the world today.

A year hence, a writer bearing the unlikely name of Russel Seeds cited Speedway president Jim Allisons apparently off-the-record remark about the problem of unresponsive race spectators. Weve got to do something to make em sit up, Allison snorted. If the thing is going to be a funeral, lets take a shot at first class music and flowers. Back in 1922 the Speedway had, in fact, published a sketch of a racer sharing a cordial cigarette interlude with the Grim Reaper allegorically depicted as a gowned skeleton.

On the brighter side, what purported in 1927 to be the largest band in the world passed in review before Sgt. Alvin C. York, whom Gen. John Joseph Pershing called the greatest civilian soldier of the war. Paul Whiteman and his Old Gold Band jammed at the Speedway in 1929, after which the joint fell under full red-alert siege, with a deafening rollout of one multiple report bomb, two salute bombs, a parachute smoke bomb, an Italian flag bomb, a British flag bomb, a French flag bomb and finally an American flag bomb. Grandstand hayrakes went so battlefield ballistic that the track continued its blitzkrieg a year later, throwing in an artillery shell bomb, a multiple report flag bomb, and a comet flash bomb. Henceforth, race day has begun with a bang, when the threatening sound of an explosion signals the opening of spectator gates. In fact, by 1947 the track had appointed a short-fused incendiary guy named C. C. Naftzger as its own in-house bomber. If you heard an explosion, chances are that Naftzger had something to do with it.

It worked supremely well. Chicago Herald-Examiner sports editor Warren Brown proclaimed in 1932, the year that Karl C. Krafts Speedway March first thundered across the acreage, that although hed witnessed the Kentucky Derby, and the likes of Bobby Jones, Babe Ruth, and Red Grange in the fevered pitch of battle, he opted for the Indianapolis 500 entertainment package for what he called the doggondest five hours or so... of never-know-what-will-happen-next. Indianapolis newspaper-man Bill Fox, Jr. who acknowledged in 1931 that The Indianapolis Motor Speedway has a passion for bombs, sarcastically advised in 1933 that the average spectator is one who will love the big parade and bombs at the start, and then focus attention on the track[,] ready to cheer the young man who will take such pride in beginning a checkered career.

It was commentator John Fitzgerald, however, who was among the first to apprehend the 500-mile race as unabashed theatrics in overdrive. The largest band in the world plays the overture, he wrote in 1937, the races silver anniversary. The curtain is raisedthe drama already at a furious pitcha million thrills are being born on the huge stage. And the endingthat, my friends, is the part written by Destiny, revealed as the afternoon sun shines its brightest upon the Speed Spectacle. The audience, said scribe Tom Ochiltree deprecatingly in 1939, consists chiefly of a democratic army of the shirt sleeve, pack-your-own lunch type. They are clerks, small store keepers, farmers and mechanics[,] and for them the whole thing is a combination community picnic and predated Halloween in county fair surroundings, multiplied a thousand fold. John Hillman rose fearlessly to the defense of the common man in 1947. Were folksy people out here in Hoosierland, he noted. We like picnics. We like reunions. We like an open house. And Speedway Day is all of these. In 2001 the Speedway went one better, by honoring all the mothers at the track on May 13.