RED  LIGHTNING BOOKS

LIGHTNING BOOKS

This book is a publication of

Red Lightning Books

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

redlightningbooks.com

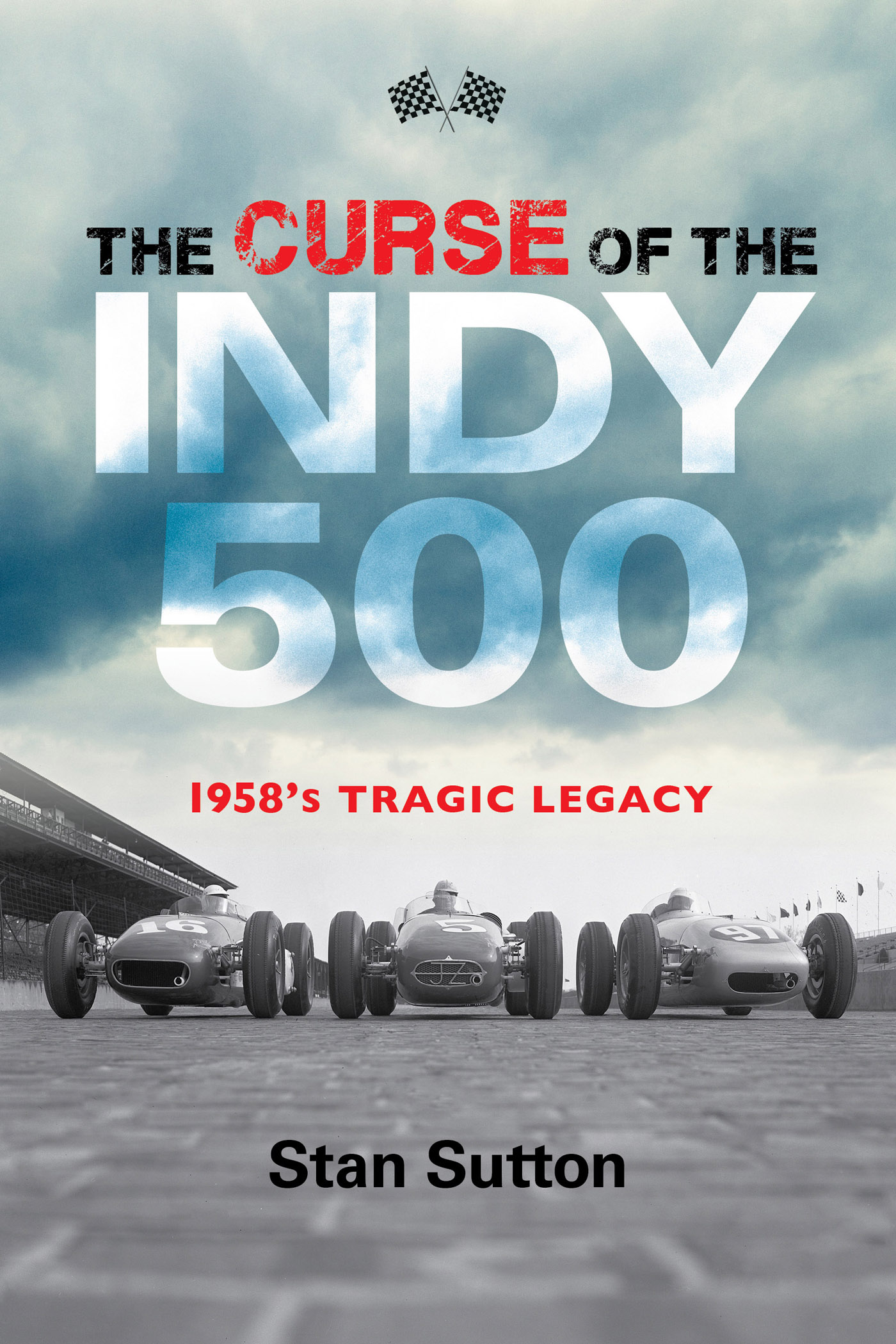

2017 by Stan Sutton

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

978-1-68435-000-1 (paperback)

978-1-68435-001-8 (cloth)

978-1-68435-002-5 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

To Aeden and Avery

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SINCE I FIRST HEARD A RACING ENGINE OVER THE RADIO IN 1946, THE Indianapolis 500 has continually replenished my memory bank. From my earliest days visiting the track to the last time I drove through the infield tunnel at five in the morning, the Speedway has been a home away from home.

Every new track record, every smell of methanol, even every rain delay was a trip to paradise. When I became a sportswriter, every fourteen-hour working day saw me where I wanted to be. Nothing equaled standing in Mario Andrettis pit, or asking Rick Mears a question, or listening to a race car fire up in Gasoline Alley.

I owe a lot of people for the chance to do this. Most of all my dad, who took me to the 1958 race that remains implanted in my memory. Especially to my wife, Judy, who didnt complain when I spent every Mothers Day at time trials. But also to my friends at the Speedway, who once came up with an extra parking pass when I lost mine. Also, to public relations folks such as John Love, Hank Abts, Anne Fornoro, and Tom Blattler, who got us in touch with busy drivers when we needed them.

To reporters there are two pieces of hallowed ground inside the track. One is the present media room, which has more television sets than H. H. Gregg and more room to work than the inside of Hinkle Fieldhouse. Even more precious among our memories is the cramped, smoky, and often filthy press room that preceded it. Race day it was so crowded that some reporters sat on the floor with computers on their laps.

The carpet there predated Wilbur Shaw, and late in every workday public relations rep Michael Knight would drag a large cooler of beer across the rug, striving to cool everyones taste buds. Sooner rather than later, the Speedway staff asked him to stop because he was ruining the carpet.

Still, many Speedway employees of that day remain among my friends: Fred Nation, Bill York, Tim Sullivan, Eric Powell, Jan Shaffer, Josh Laycock, Dick Mittman, Bob Walters, Ron Green, Mai Lindstrom, and too many others to remember. Also, the press corps with writers such as Robin Miller, Curt Cavin, Dave Van Dyke, Phil Richards, Charley Hallman, Charlie Vincent, Bill Benner, Tim May, Angelique Chengelis, Mike Vega, Terry Reed, Bob Markus, Tom Reck, and Al Stilley.

Thanks to Ashley Runyon of Indiana University Press for challenging me to write this book and for her patience in overseeing it. Likewise to her colleagues: Peggy Solic, John Decker, and Rhonda Van Der Dussen. Project manager Darja Malcolm-Clarke and copyeditor John Mulvihill were true professionals.

Special thanks to Jeff OConnor and Bryce Mayer, who welcomed me to North Vernon and made me feel at home there. And to Bill Marvel, who remembers the 1958 race and probably is the biggest racing fan I know. His help was unbelievable.

My wife, Judy, and daughter, Shari, guided me through the countless technical problems encountered by a child of the 50s.

Most of all, those of us who love racing owe an incalculable debt to those who paid the ultimate price in a race car. Godspeed to you all.

A Convoluted Account of the Crash

IN THE SPRING OF 1958 THE INDIANAPOLIS 500 COULD ARGUABLY CLAIM to be one of Americas top five sporting events. In the same category were the World Series, the Kentucky Derby, the next heavyweight championship fight, and probably the Rose Bowl. The Final Four basketball tournament carried less impact then, and the Super Bowl wasnt even on the horizon.

The 500, the longest and most unique race until stock cars copied the format in the 50s, prospered because of Americas growing fascination with the automobile. Fans that went to races in Model Ts were obsessed with speed and noise, not to mention danger. Critics of the sport, and there were many, often accused followers of attending races only to see accidents, and perhaps even fatalities. Despite 11 deaths in the first 10 years of racing at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, crowds continued to come.

Even two world wars failed to stymie the interest, although the 500 was abandoned from 1942 to 1945, and the Speedway was overgrown with weeds. When the race resumed it was popularized by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Radio Network. While obviously primitive, the IMS Network drew vast numbers of listeners who appeared to be mesmerized by the sound of racing engines.

There were few options available to the announcers except to occasionally give the standings, conduct a few interviews, and keep the microphones open to the sound of racing engines.

Much of the time was filled by announcers remarks such as, That was Ted Horn, or, That sound was Rex Mays moving into the lead.

On May 30, 1958, thousands of cars rolled into the infield at dawn, maneuvering for a prime spot where they could see race cars go past. In those days fans were allowed to construct scaffolding alongside their cars from which to better watch the race.

As the eleven oclock start approached, tension mounted as in no other sport. Thirty-three cars lined three abreast suddenly lurching up to speed seemed to carry the risk of military battles.

One of the first-time announcers at the 1958 race was Lou Palmer, an Indianapolis radio personality hired to announce happenings in the third corner of the 2.5-mile track. The chief announcer was the golden-voiced Sid Collins, who was supported by five subordinates around the track. When an accident occurred, it was up to this crew to describe the incident.

Being a rookie, Palmer was assigned to the third turn, where the chances of a first-lap crash were considered less likely than in the first two corners. Although drivers are warned not to try to win the race in the first turn there was more concern than usual that pole-sitter Dick Rathmann and second-fastest qualifier, Ed Elisian, might take undue chances.

Palmer, who had lived in Indiana only five years, settled into his spot outside the third-turn wall. He couldnt know how quickly bad things were to happen. Rathmann and Elisian began their duel with Rathmann jumping in front, but as the two front-runners approached the third corner Elisian pulled in front.

Next page