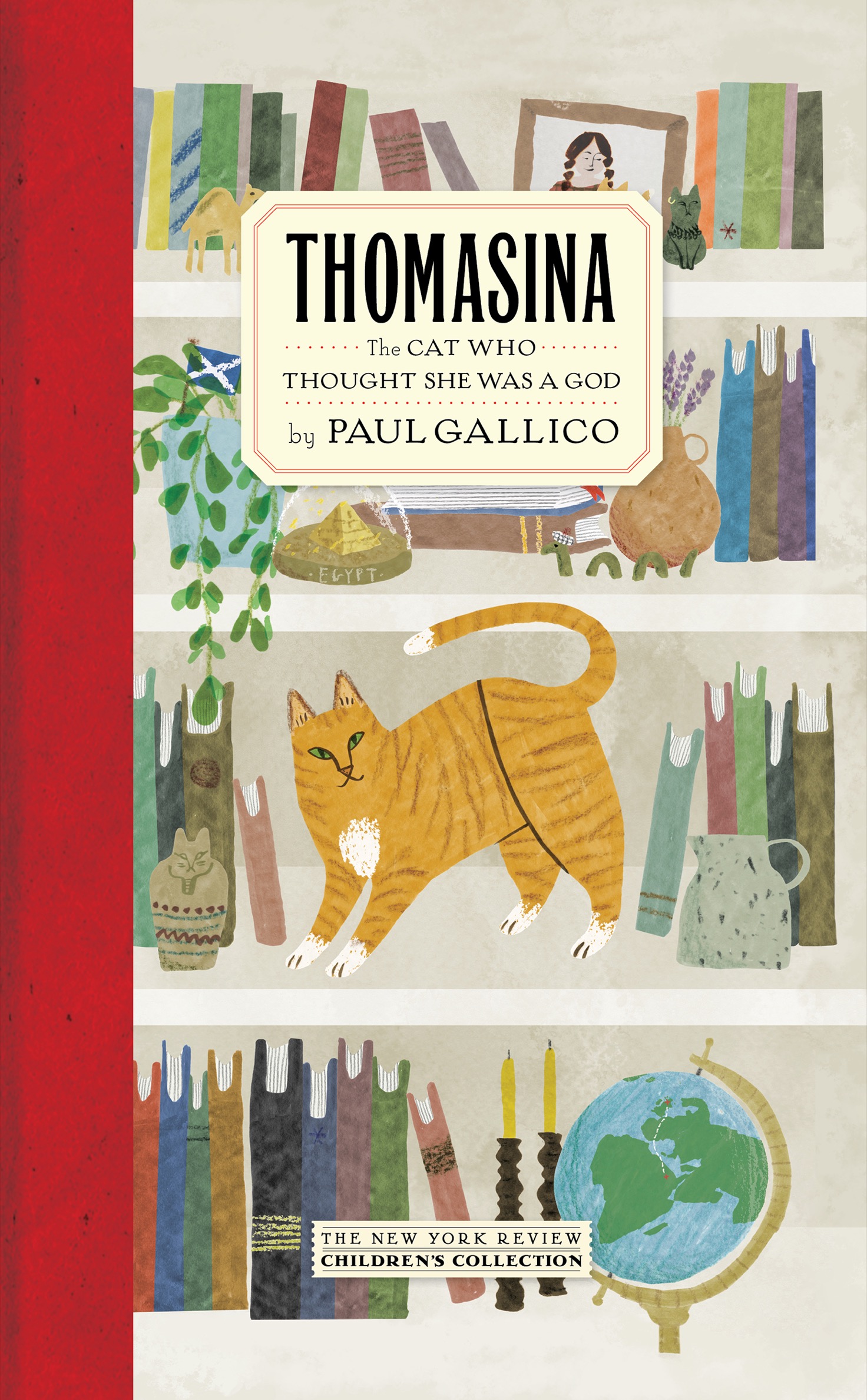

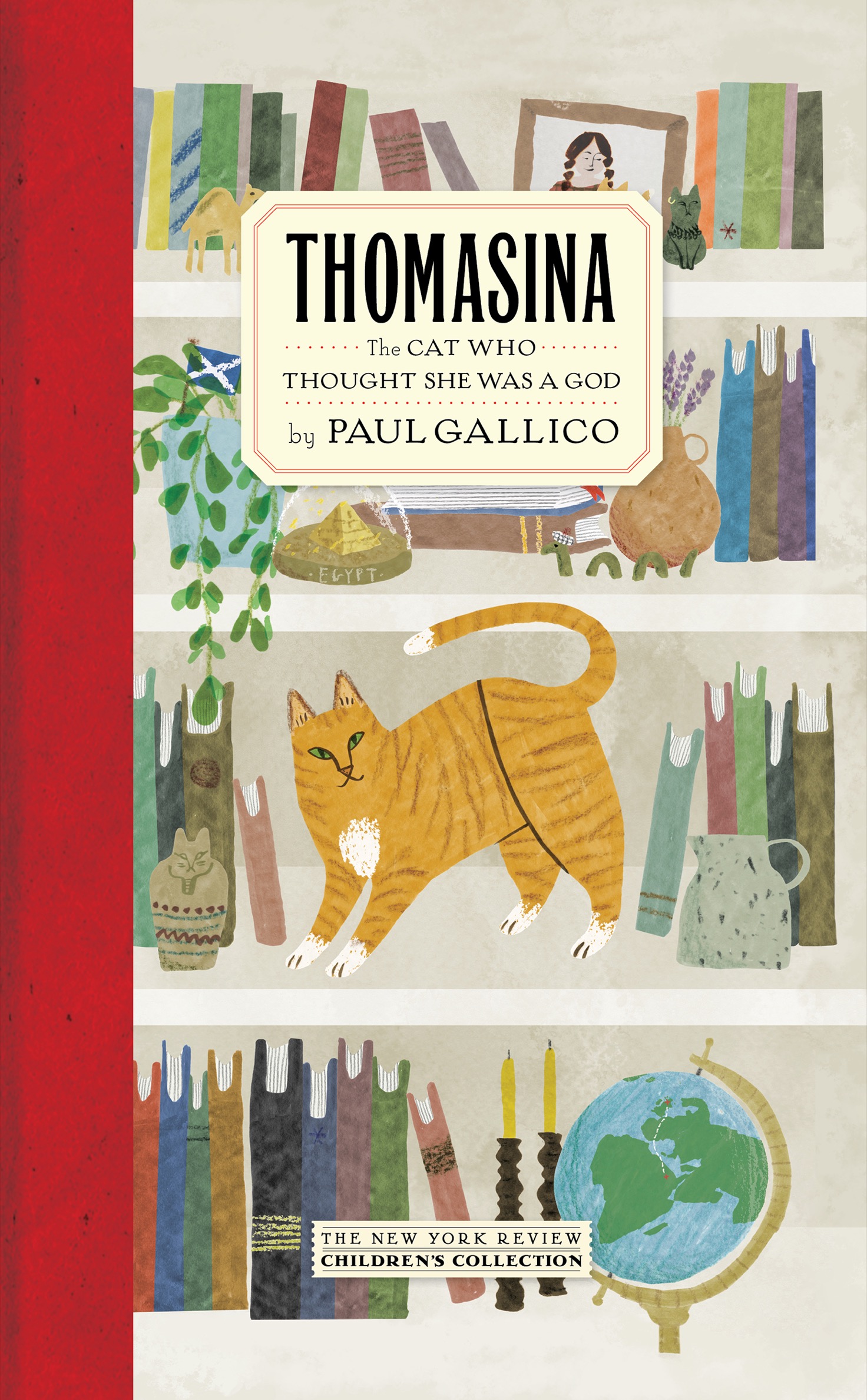

PAUL GALLICO (18971976) was a popular and prolific sports columnist, screenwriter, and author of books for adults and children. He was born in New York City to an Italian immigrant musician father and a mother who had studied to be a singer, and paid his way through Columbia University by tutoring children and working as a longshoreman. He began his career at the New York Daily News, where he soon became famous for his adventures with star athletes of the day. In 1937 he published the essay Farewell to Sport and turned to fiction, with stories appearing in magazines including Cosmopolitan, The Saturday Evening Post, and The New Yorker. Among his forty-one books are the novella The Snow Goose (1941); Manxmouse (1968, often cited by J. K. Rowling as one of her favorite books); Mrs. Arris Goes to Paris (1958) and its four sequels; The Poseidon Adventure (1969), the basis for the hugely successful 1972 film; and The Abandoned (1950; available from New York Review Books). From 1950 until his death Gallico lived outside of the United States, mostly in England, Antibes, and Monaco.

P AUL G ALLICO

T HOMASINA

The Cat Who Thought She Was a God

THE NEW YORK REVIEW CHILDRENS COLLECTION

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1957 by Mathemata Anstalt

All rights reserved.

First published in the United States of America in 1957

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph in 1957

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gallico, Paul, 18971976, author.

Title: Thomasina : the cat who thought she was a god / by Paul Gallico.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2018] | Series: New York Review Childrens Collection | Originally published in 1957 in Great Britain. | Summary: When seven-year-old Marys father puts her beloved cat, Thomasina, to sleep, Mary stops speaking to him and becomes gravely ill until Lori, a woman rumored to be a witch, restores Thomasina to health and Thomasina saves Mary.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017061045| ISBN 9781681372327 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681372334 (epub)

Subjects: | CYAC: CatsFiction. | Human-animal relationshipsFiction. | Fathers and daughtersFiction. | VeterinariansFiction. | Animal rescueFiction. | SickFiction. | Family lifeScotlandFiction. | ScotlandHistory20th centuryFiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.G137 Th 2018 | DDC [Fic]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017061045

ISBN 978-1-68137-233-4

v1.0

Cover design by Louise Fili, Ltd.

Cover illustration by Jenny Collins

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

To Virginia

There is no such town as Inveranoch in Argyll, nor are there any such people alive or dead as written about herein. This is a work of fiction.

P. G.

T HOMASINA

C HAPTER O NE

M R A NDREW M AC D HUI , veterinary surgeon, thrust his brick-red, bristling beard through the door of the waiting-room next to the surgery and looked with cold, hostile eyes upon the people seated there on the plain pine chairs with their pets on their laps or at their feet awaiting his attendance.

Willie Bannock, his brisk, wiry man-of-all-work in surgery, dispensary, office and animal hospital, had already gossiped a partial list of those present that morning to Mr MacDhui and which included his friend and next-door neighbour, the Minister, Angus Peddie. Mr Peddie, of course, would be there with, or because of, his insufferable pug dog whose gastric disturbances were brought on by pampering and the feeding of forbidden sweets. Mr MacDhuis glance dropped to the narrow lap of the short-legged, round little clergyman and for a moment his eye was caught up in the unhappy, milky one of the pug rolled in his direction, filled with the misery of belly-ache, and yet expressing a certain hope and longing as well. The animal had come to associate his visits to this place, the smells and the huge man with the fur on his face with relief.

The veterinary disentangled himself from the hypnotic eye and wished angrily that Peddie would follow his advice on feeding the animal and not be there wasting his time. He noted the rich builders wife from Glasgow on holiday with her rheumy little Yorkshire terrier, an animal he particularly detested, with its ridiculous velvet bow laced into its silken top-knot. There was Mrs Kinloch over the ears of her Siamese cat which lay upon her knee, occasionally shaking its head and complaining in a raucous voice, and, too, there was Mr Dobbie, the grocer, whose long and doleful countenance reflected that of his Scots terrier who was suffering from the mange and looked as though a visit to the upholsterer would be more practical.

There were half a dozen or so others, including a small boy, who he seemed to have seen somewhere before, and at the head of the line he recognised old, obese Mrs Laggan, proprietress of the newspaper and tobacco shop who, with her nondescript mongrel, Rabbie, his muzzle greyed, his eyes rheumy with age, was a landmark of Inveranoch and had been so for years.

Mrs Laggan was a widow, and had been for the past twenty-five years of her seventy-odd. For the last fifteen of them, her dog, Rabbie, had been her only companion, and his bulk draped across the doorstep of Mrs Laggans shop was as familiar a figure to natives as well as visitors to the Highland town as that of the fat widow in her Paisley shawl. Since the doorstep was Rabbies place, nose between forepaws, eyes rolled upwards, customers of the widow Laggan had learned to step over him when entering and departing. It was said in the High Street that descendants of these clients were already born with this precaution bred into them.

Mr MacDhui looked his patients over and the patients looked back at him with varying degrees of anxiety, hope, deference, or in some cases a return of the hostility that seemed to be written all over the well-marked features of his face, the high brow, the indignantly flaring red-tufted eyebrows, commanding blue eyes, strong nose, full and sometimes mocking lips, half seen through the bristle of red moustache and beard and the truculent and aggressive chin.

His eyes and, above all, his manner always seemed cold and angry, perhaps because, it was said in Inveranoch, he was on the whole a cold and angry man.

A widower of the stature and flamboyance of Mr Veterinary Surgeon MacDhui was subject enough for gossip in a Highland town the size of Inveranoch, in Argyll, where he had been in practice for only a little over eighteen months. By the nature of his profession he was a figure of importance there since he looked after not only the personal and private pets of the townspeople, but was responsible also for the health of the livestock raised in the outlying farms of the district, the herds of Angus cattle and black-faced sheep, pigs and fowl. In addition, he was the appointed veterinary of the district for the inspection of meat and milk and hygienic dairies as well.

The gossips allowed that Andrew MacDhui was an honest, forthright and fair-dealing man, but, and this was the opinion of the strictly religiously inclined, a queer one to be dealing with Gods dumb creatures, since he appeared to have no love for animals, very little for man, and neither the inclination or the time for God. Whether or not he was an out and out unbeliever as many claimed, he certainly never was seen in Mr Peddies church, even though the two were known to be good friends. Others claimed that when his wife had died his heart had turned to stone, all but the corner devoted to his love for his seven-year-old child, Mary Ruadh, the one who was never seen without that ill-favoured, queer-marked ginger cat she called Thomasina.