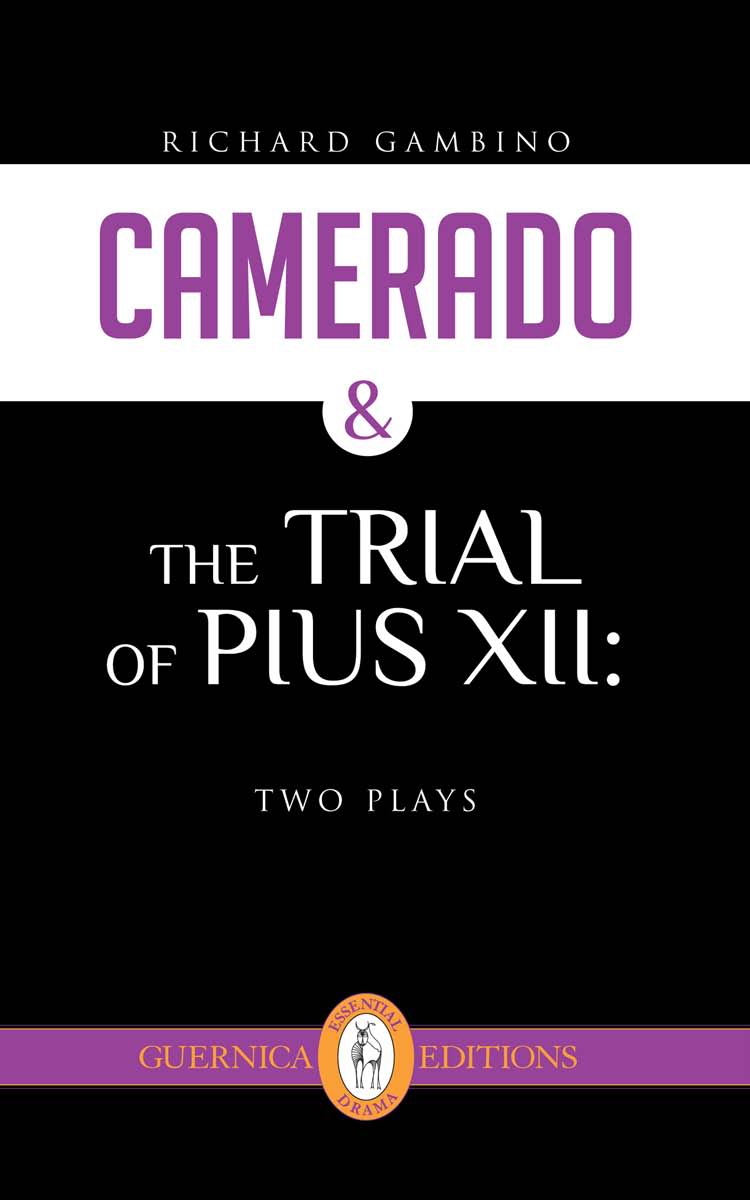

Camerado, Followed By

The Trial of Pius XII

Richard Gambino

Guernica

Toronto Buffalo Berkeley Lancaster (U.K.) 2013

Contents

For Gail,

who made these two plays so powerfully alive in stage productions, and with the hope that Liam and Beatrix live all their lives in the greatness of the human spirit Walt Whitman so well illuminated.

Camerado

Characters

Walt Whitman

Man: He plays all the male speaking roles, except Whitman.

Woman: She plays all the female speaking roles.

Act I

Setting: The curtain is always up. The play takes place in the parlor/office of Whitmans last home in Camden, New Jersey. It is a cozy room of a small cottage, with simple, humble, but comfortable, old, midnineteenth century furniture. The furniture includes his large rocking chair, visitors chairs, his desk, a wheelchair, and a combination chaise/bed. There are piles of books and papers everywhere.

Time: The entire play takes place in a single day in the autumn of 1891, from morning to dark.

Throughout the play, Whitman will be talking to the audience, except for conversations with people on stage, played by Man and Woman, who arise from Whitmans memory and thoughts. Changes in scene, time and mood are to be accomplished by uses of lighting, costume changes, rear slide projections, and audio recordings. The suggested slides and recordings can be revised and augmented by the director.

At rise: stage dark. Light up and we see Whitman sitting in the large rocking chair. Morning light is coming in from the windows. Despite Whitmans white hair and beard, his voice is ten years younger than his age of seventy-two. His body is that of an ill man, no longer physically robust, but he telegraphs great inner power. He is six feet tall, and is dressed in the workmans clothing he liked to wear: a homespun ivory-white shirt wide-open at the collar, revealing a skyblue undershirt, loose trousers devoid of belt loops, held up by a thick belt, and well-worn hiking boots of soft leather.

He is reading a copy of the New York Times. He snorts to himself, then looks at the audience. He is angry.

WHITMAN

(to the audience) Listen to this! The New York Times says my writing is full of picturesqueness and strength. But the paper still says my poems are the reverse of the poetic. They are banned in the state of Massachusetts, and the Society for the Suppression of Vice burns my book in New York. (He snorts again.) When I first published the same work years ago, the Times said that I rooted around like a pig among rotten garbage. Not to be outdone, the New York Tribune said that I took off my trousers in public. (He shakes his head in frustration.) I say published because I not only wrote the words, but I published them at my own expense. I also helped set the type for the first edition of Leaves of Grass, and operate the press. I could get no publishing house to print my poems. And none would distribute them. My work was deemed obscene! Still is. So I carried copies to the bookstores on my back. I sold them on the streets of Brooklyn and Manhattan. Why obscene? Well, my message to ordinary men and women is to find the cosmos, whole and complete in each individual. It is denounced as narcissism. My celebration of my body and yours is termed the issue of a slop bucket. My joining of the soul and body is called indecent. As if the only way to celebrate the union is to reduce the soul to the body. I raise the body to the soul! It seems my blasphemy is in seeing God in each man and each woman. (His mood changes. He becomes wry, mischievous.) But back then there was one notice that truly appreciated my call to infinitude in everyday life. I think I can still remember some of it. (Closing his eyes in an effort of memory. We hear a voice offstage reciting the lines.) Very devilish to some, and very divine to some, will appear the poet of these new poems ...they are ...affectionate, sensual ...undraped, regardless of models, regardless of modesty or law, and scornful ...of all except the authors own presence and experience ... Who wrote this anonymous review? I did. You say, of course, This fellow has not reviewed his work, but himself! Yes! (He becomes sad, heartbroken.) But there was one critic I should say two who hurt me badly. A reporter searched out my brother, George, and asked him about Leaves of Grass. George said, I saw the book, but didnt read it at all didnt think it was worth reading. Mother thought as I did. You see, they were cowered by the yawpers who slandered my work. (Pause. Insistent.) But I will be understood before I die! I am determined! The ninth edition of my work will be definitive. Has to be Im dying, and not afraid of it. But Walt Whitman, the man, would be understood. In this my supporters have been almost as deficient as my critics. The first famous man to champion my work was Ralph Waldo Emerson, and I was grateful to him. I went to Boston, to thank him. We strolled on the Common for two hours, he the talker and me the listener. (Change of lighting. Emerson appears onstage. Whitman and Emerson walk as if strolling on the Boston Common. Projections of the Common in antebellum times.)

EMERSON

(friendly, fatherly) My dear Walt, I am not blind to the wonderful worth of Leaves of Grass. Remarkable!

WHITMAN

Thank you, sir.

EMERSON

In matter of fact, your writing is the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed to the world. Henry David Thoreau calls it a trumpet note ringing throughout the American camp, and I agree.

WHITMAN

You have both been most kind in your public praise of my book.

EMERSON

Your poems, well, they meet a requirement, a demand, I set for American writers.

WHITMAN

What would that be?

EMERSON

Our authors have seemed to me too sterile and stingy in nature. Its as if theyre too aggressively colorless. Theyve been making our American wits fat and mean.

WHITMAN

(nodding) Ah.

EMERSON

I have great joy in your free and brave thought. I find in your poems incomparable things said incomparably well. Your courage of treatment delights, and your large perception inspires!

WHITMAN

Well, you are very kind, and I thank you.

EMERSON

There is but one caution. One request I would make to you.

WHITMAN

Please do.

EMERSON

In tone, some of your writing ...your Calamus poems, for instance. They are ...untoward. In tone, mind you, not in merit.

WHITMAN

Untoward?

EMERSON

Please understand. When I first read yourpoems, I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion. But their solid nature is a certainty.

WHITMAN

Then what do you mean by untoward?

EMERSON

Your superbly graphic descriptions, and great stretches of imagination ...There is a certain delicacy they challenge. (Whitman stops strolling, and he and Emerson face each other squarely.)

WHITMAN

Please make yourself plain, Mister Emerson, I beg you.

EMERSON

One cannot leave your book lying about for chance readers. And one would be sorry to know that any woman had looked at it past the title page.

WHITMAN

I see. You agree with my critics, then, all those who call my poems indecent.

EMERSON

No. Your personal exploration of the boundlessness of the spirit is nothing less than divine.

WHITMAN

Then?

EMERSON

Let them be unimpeded, unburdened. Excise some of the provocative lines that obstruct their acceptance. Or change them.

Next page