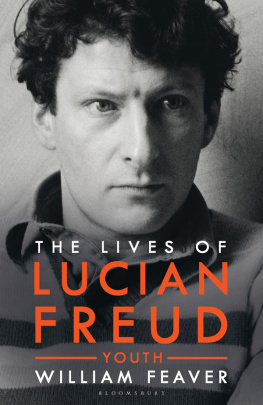

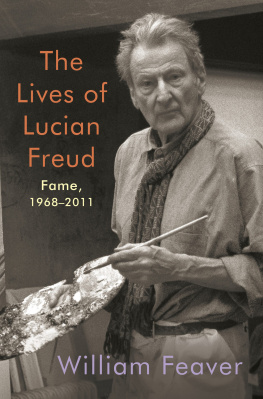

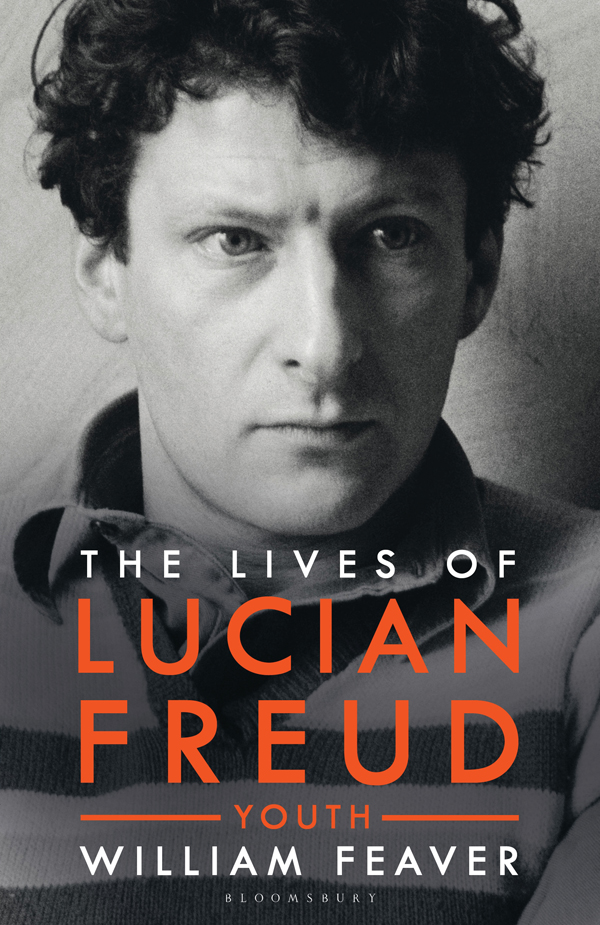

THE LIVES OF LUCIAN FREUD

Andrea Rose

ALSO BY WILLIAM FEAVER

The Art of John Martin

When We Were Young

Masters of Caricature

Pitmen Painters

Frank Auerbach

Contents

The day we first met, in 1973, I told Lucian that for interview purposes I just wasnt interested in his private life. All that mattered was the work.

Time passed and in later years whenever he taxed me with having been so artless my response was that what perhaps had sounded like a pledge had been a mere clearing of the throat. By then of course it had become obvious to me that the work reflected the life and embodied the life, and because the life Lucian led was spent more in the studio than anywhere else that was its commanding peculiarity. As he himself said Everything is biographical and everything is a self-portrait. Since his relationships tended to be compartmented and the vicissitudes that eddied around various passions so clearly affected him, it seemed to me that some sort of consolidated account of them extending beyond self-portraiture was now needed.

Initially this book was to have been a brief account of Freud the artist, but in the late 1990s, as the tapes accumulated and reminiscences flowed, we agreed that what Lucian had taken to referring to as The First Funny Art Book was outgrowing its prospectus, so it was shelved for the time being, Lucian half-heartedly assuring me that he would have no objection to a novel appearing once he was dead. Working with him on a number of exhibitions made the oeuvre ever more familiar to me and we went on talking, primarily on the phone, almost daily. The notes I took from the countless conversations (How old am I now? he would often ask me or, less specifically, How goes it?) are the chief source for these two volumes of biography.

Always wanted never to have anything known about me

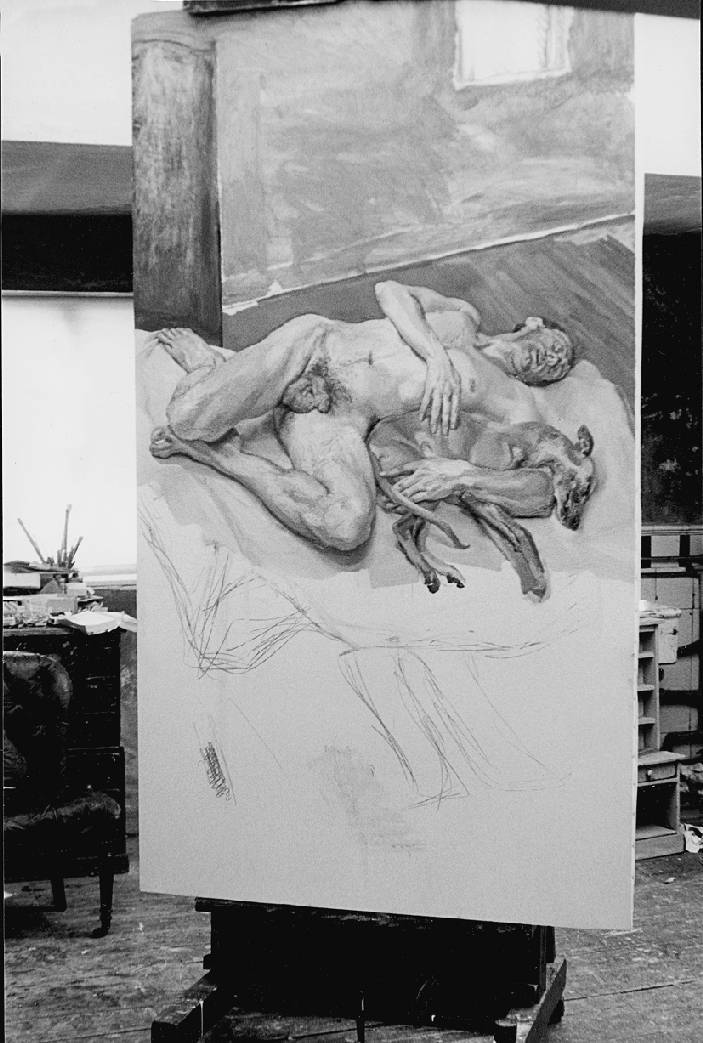

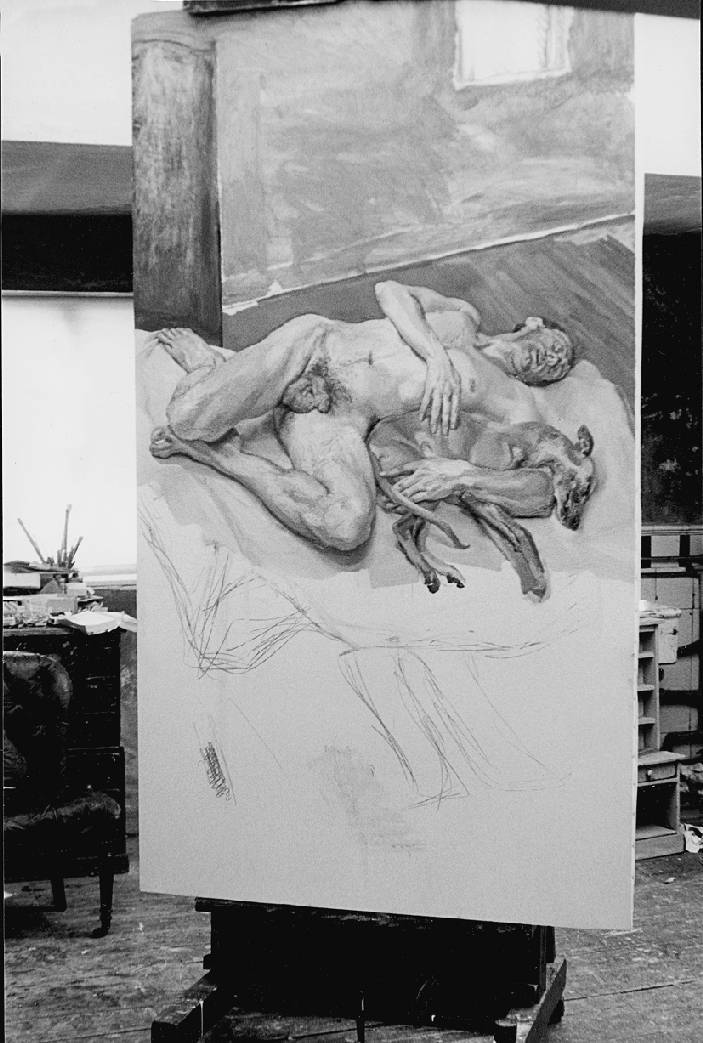

There were, as usual, several pictures on the go. The main one, on an easel directly under the skylight, was so far little more than eyes and chin, floorboards edging in, indications in charcoal of body on bed, a muzzle and smudge where Pluto the whippet would lie and a patch of white at the foot of the bed where a woman was to have stood. She had become intrusive, the painter had decided. A lesser distraction was needed. Possibly something under the bed, he said.

While what was to become Sunny Morning Eight Legs preoccupied Lucian Freud in daylight hours, others were worked on through evening sessions and into the night. Rose, one of his daughters, and her husband Mark were sitting for a double portrait, their heads distinct but as yet unrelated, the gap between them just beginning to be realised. Ive already put some air in here, was the comment. Another daughter, Ib, had been sitting with a book for a second daytime painting. The relationship of head to Proust had worked out well but more breathing space was needed and so the canvas had been extended. Proceeding as he did by accretion, form by form, Freud often found enlargement necessary. That way, ideas grew. The seams that zigzagged down all four sides of Ib Reading would soon be painted over, leaving scars visible only in a raking light.

Freuds Holland Park studio: work in progress on Sunny Morning Eight Legs , at a six-legged stage, 1997

Freuds working methods were demanding while unassuming throughout. Presuming nothing save the presence of whoever or whatever he had felt like painting, he would go ahead with little or no preconception beyond the glimmerings of potential. Early on, as a beginner, there had been the buzz, the magic almost, of making imagined things substantial, making them convincing somehow. In that way, once I got going, they led me on; I liked to have nothing there so that I felt they came from nowhere. Later he came to depend on engaging with what he actually saw, intuition reminding him, by the by, that a sitters outward appearance was to do with whats inside his head.

No other painter in modern times has more straightforwardly made so much of the particular. He used to mock me for being obliged, he said, as an art critic to maintain eternal vigilance. Which of course was what in practice he demanded of himself. His was an intent alertness sustained hour by hour, week in week out. Painting had to be unremitting, never (in his words) indulgent to the subject matter; Im so conscious that that is a recipe for bad art. He talked about perseverance as an instinct. Ruthlessness too, he assumed, but that went without saying. I always thought that an artists life was the hardest life of all.

Painting absorbs whatever affects the painter. Every consideration, emotional or otherwise, Freud believed, stretches a paintings potential. I dont think theres any kind of feeling you have to leave out. If the feeling wasnt there, then ultimately the painting failed. Yet the feeling in a painting was necessarily filtered, distanced, objectified. He stressed the need to avoid false feeling or gratuitous fervour. I dont want them to be sensational, but I want them to reveal some of the results of my concentration. His concentration over the years yielded paintings, drawings and etchings that fix insistently on what we are whoever we are, on the motif whatever it may be, getting a hold on the ingrained uncertainties that spice a life.

Freud liked unpredictability, particularly at the outset. I try and vary the way I start. What I mean is, sometimes I put down a lot of paint but sometimes say on a single figure I start in a different place. Often Ive started round the stomach and different parts. Its to do with my horror of method, which may come of my having had such a rigorous method at the very beginning.

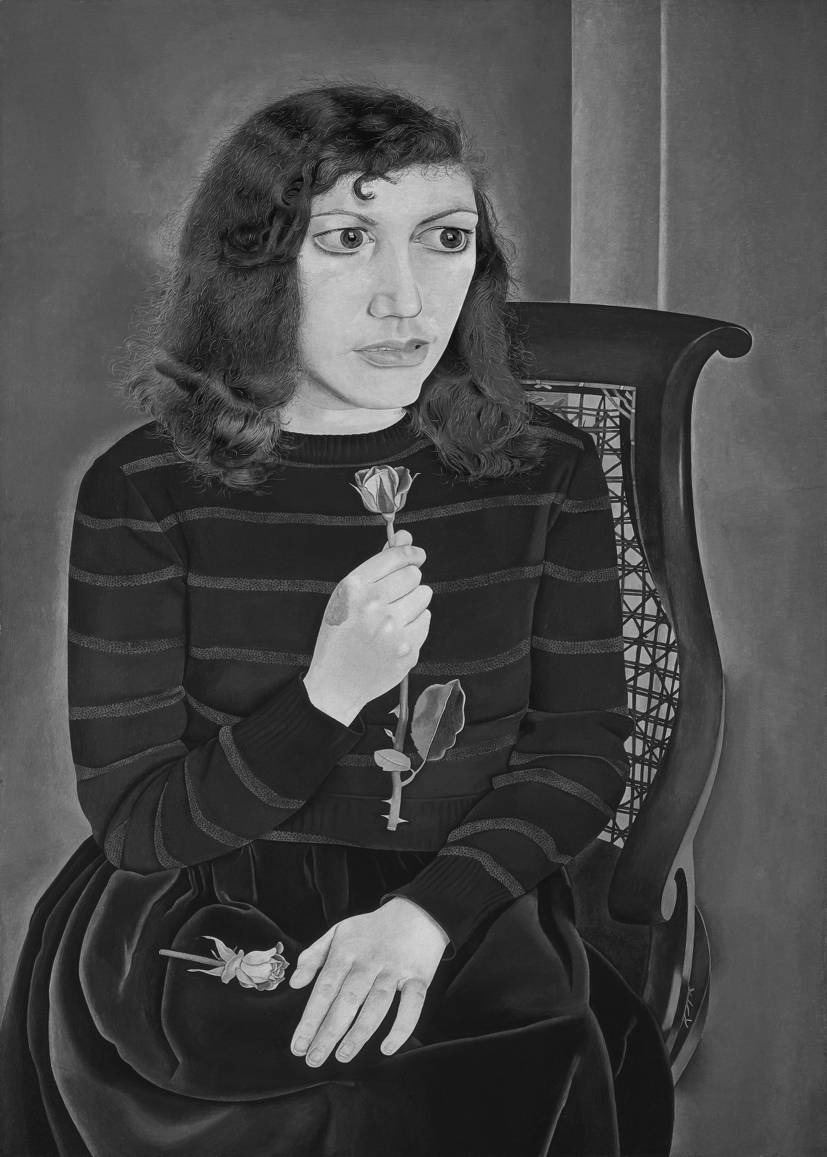

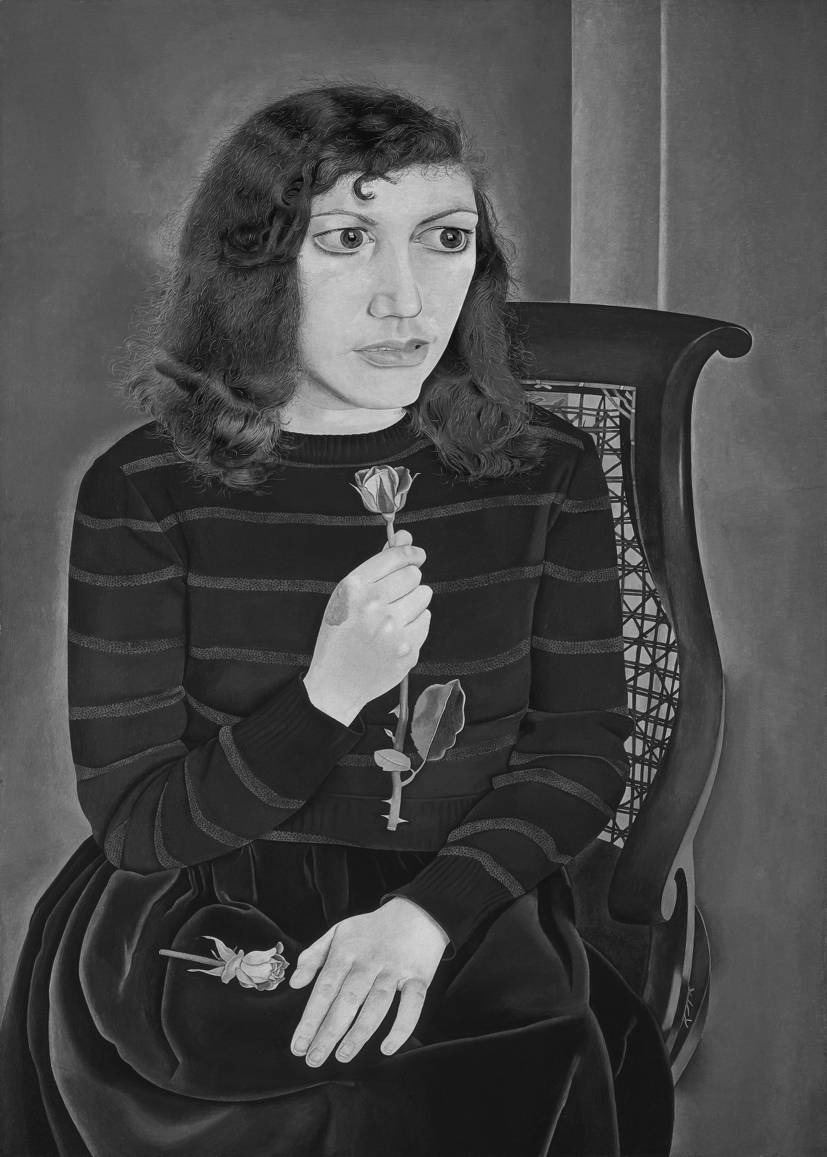

That method, conspicuously exhaustive, culminated in Girl with Roses (19478), considered by Freud his first real picture and certainly one of the first to advance on a sizeable scale the notion of close attention as the essence of a relationship. The girls stare is subjected to that of the painter. She looks towards a window shown reflected in her eyes. Such detail may prompt metaphysical analogy (windows into the sitters soul), but it represents more the desire of an exacting young painter to make the image alert.

Girl with Roses, 19478

The sitter was Kitty Garman, a daughter of Jacob Epstein whose bust of her done three years previously represented her as a sort of naiad with a streaming head of hair. Epstein talked of a trembling eagerness of life pulsing through such portrait sculpture: Head, shoulders, body and hands, like music. His future son-in-law, the spiv Lucian Freud, as he was to refer to him after the divorce, saw Kitty plain: wide eyes, braced shoulders, seated as rigidly as a playing-card queen. He had painted her a couple of times before, initially young and artless in a busmans jacket and then holding a tabby kitten as though proffering a decanter, the relaxed limpness of the paws indicating a kindly grip on the neck of this namesake cum attribute.

Girl with Roses exemplifies wariness. It harks back to One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery , a selection made by the Gallerys Director Kenneth Clark and published in 1938 in which, page after page, the black and white photogravure reproductions parade stimulating qualities: the poise of Holbeins Christina of Denmark , the salon aplomb of Ingres Madame Moitessier , one of Freuds favourite paintings and Clarks most astute acquisition for the National Gallery in his time there. Leafing through, the detail that in sudden alacrity most vividly compares with Girl with Roses is the close-up of the tabby cat clinging to the chair-back in Hogarths The Graham Children : eyes enormous, thorny claws bared.

Next page