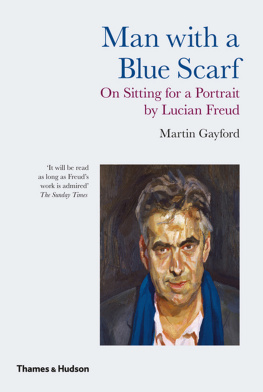

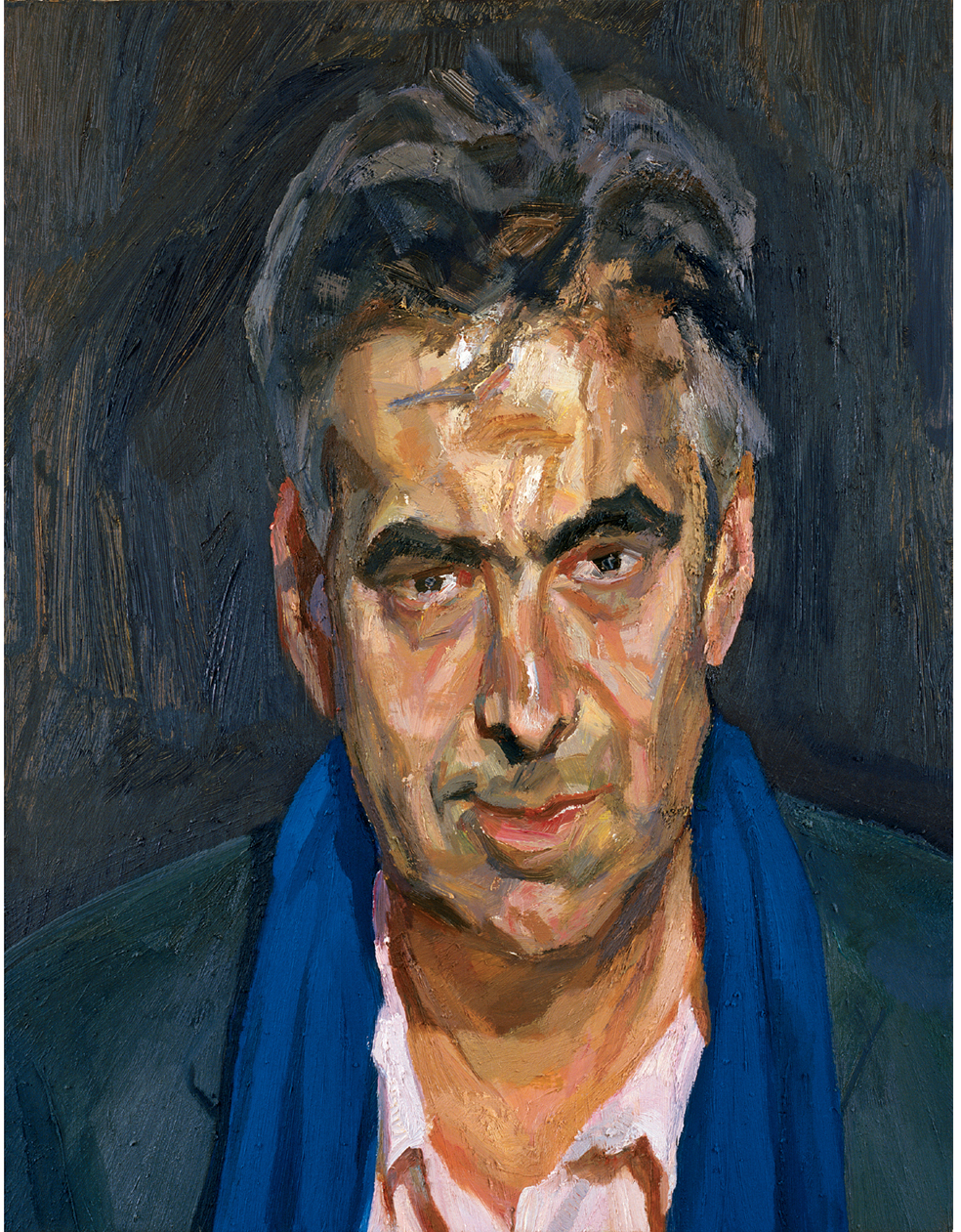

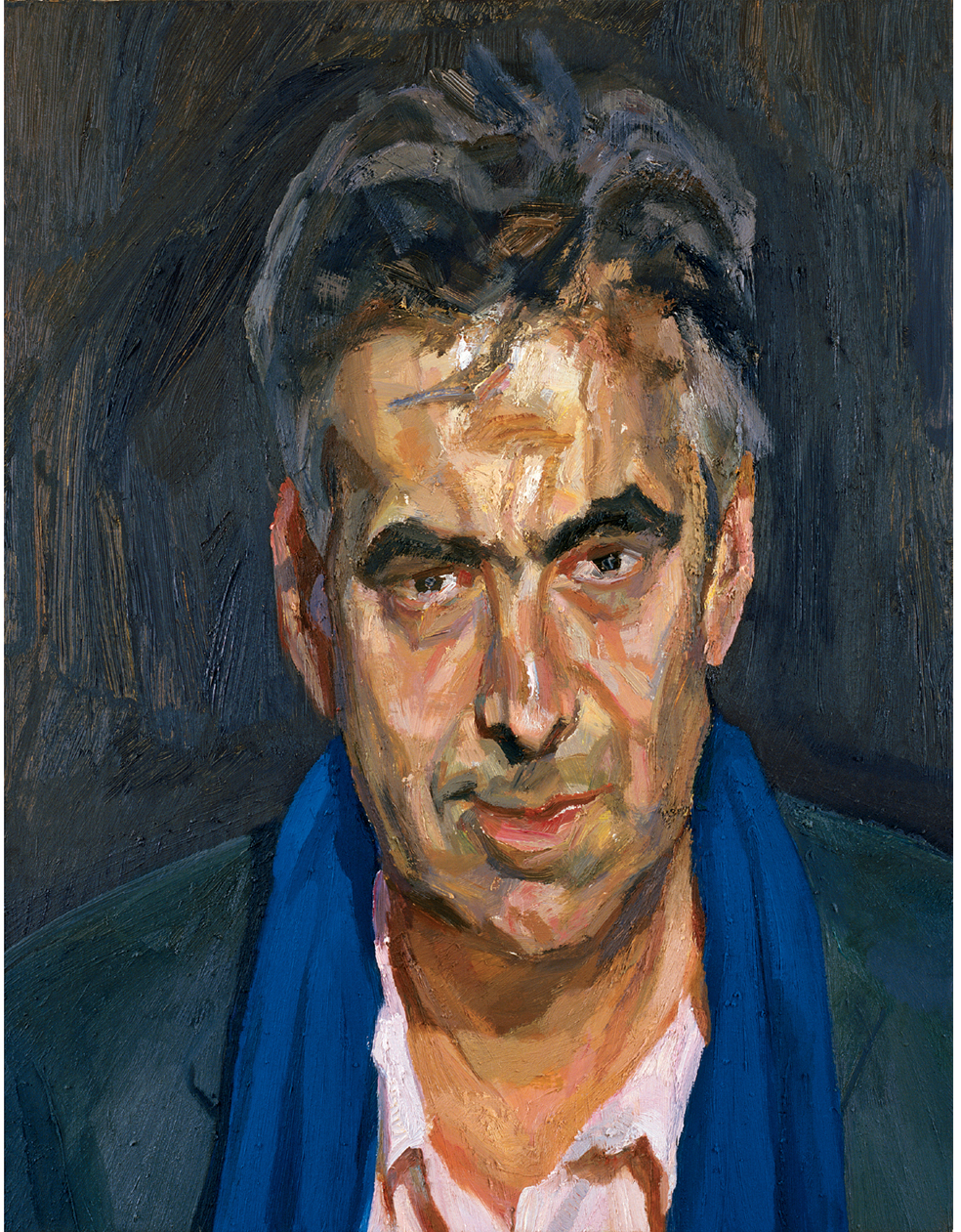

Man with a Blue Scarf, 2004. Oil on canvas, 66 50.8 (26 20). Private collection. LFA/John Riddy

MAN WITH A BLUE SCARF

Authors Note

The following is based on a diary I kept during the year and a half in which I sat for two portraits, one in oils, one etched. Some conversations and events I have omitted, in places I have amplified my thoughts of five years ago, a few exchanges and incidents have been moved a little in time to assist the narrative flow, but essentially what follows is a record of what happened in the studio.

CONTENTS

MAN WITH A BLUE SCARF

THE SITTINGS

Lucian Freud indicates a low leather chair and I sit down. Does that pose seem reasonably natural? he asks. I try to impose my ideas on my sitters as little as possible. Its a cold late autumn day and I am wearing a tweed jacket and a royal blue scarf. Perhaps, I suggest, I could keep the scarf on for the picture. LF agrees, but on certain points it soon turns out his will is law. I had thought that perhaps I could read while sitting, and had brought a book along with me, but no. I dont think Im going to allow you to do that. I already see other possibilities. He must have registered them almost instantly.

At this point LF makes chalk marks on the floorboards around the legs of the chair. This is so that we can replace it in precisely the same position with reference to the overhead light and the easel each time I come to the studio. Behind, LF positions a battered black folding screen: the backdrop to my head. Then he searches around for a suitably sized canvas among the various ones leaning against the studio wall. The first he finds is discarded as it has a dent, which he says would sooner or later cause the paint to flake off. Then he fishes another out of the corner and sets to work immediately, drawing in charcoal.

So it begins. This is how hour after hour will be spent, stretching for months into the future. Sitting in a pool of light in the dark studio, I start to muse and to observe.

I have long been convinced that Lucian Freud is the real thing: a truly great painter living among us. When, one afternoon over tea, I very tentatively mentioned to him that if he wanted to paint me I would be able to find the time to sit, my motive was partly the standard one of portrait sitters: an assertion of my own existence. For various reasons, I was feeling rather down and being painted by LF seemed a good way to push back against circumstances.

The other reason was a curiosity to see how it was done. After years of writing, talking and thinking about art, I was attracted by the prospect of watching a painting grow; being on the inside of the process. Even so, when I made that modest proposal, I didnt really expect LF to accept. Probably, I thought, he would say something politely noncommittal along the lines of, Thats a nice idea, perhaps one day. Instead, he responded by saying, Could you manage an evening next week?

I had known him for quite some time before that day, getting on for a decade. We had talked for many hours as friends, and as artist and critic. I had eaten innumerable meals in his company; together we had visited exhibitions and listened to jazz concerts. Dozens of times I had visited his studios, to look at recently finished pictures and work in progress. This, however, was different. This time, I was not looking at the picture, but being it or at least its starting point.

The experience of posing seems somewhere between transcendental meditation and a visit to the barbers. There is a rather pleasant feeling of concentrating and being alert, but no other need to do anything at all except respond to certain requests: Would you mind moving your head just a little?, Could you move the scarf just an inch? As it is, it looks a little bit dressed. At moments sitting seems an almost embarrassingly physical affair: an enterprise that concerns the models skin, muscles, flesh and also, I suppose if there is such a thing self.

I ask if talking is allowed while Im posing, and LF says it is, although I may sound like an absolute lunatic. In practice, we alternate between conversation and periods when his concentration is intense. During those he keeps up a constant dance-like movement, stepping sideways, peering at me intently, measuring with the charcoal. He holds it upright, and with a characteristic motion moves it through an arc, then back to the canvas to put in another stroke. During this process he mutters to himself from time to time, little remarks that are sometimes difficult to catch: No, thats not it, Yes, a little, Slightly At intervals he takes a wad of cotton wool from his pocket and wipes a stroke or two away. Once or twice he steps back and surveys what he has done, with his head on one side.

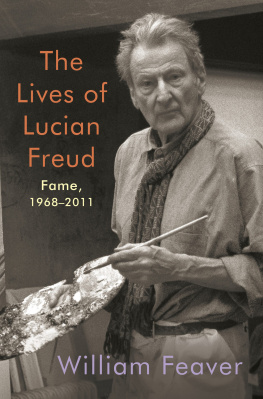

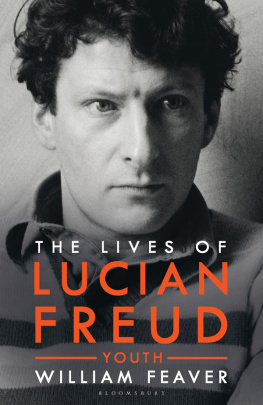

Lucian Freud has been at work for a long, long time. He was born in Berlin in December 1922. From boyhood he always intended to become a painter. His earliest surviving oil paintings date from the 1930s, by which time his family was living in England. But despite the fact that his career now stretches over six decades, it would be wrong to claim that his art is simply the continuation of a great tradition: the depiction of people, things and places from life.

It is closer to the truth to say that by an act of will and daring he revived the figurative tradition, and did so with immense conviction. Even in his youth there were many people who said that kind of figurative painting was dead. He arrived on the scene long after Marcel Duchamp had pioneered art based on found and altered objects, rather than painting or drawing. Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko were all much older than him. He worked in the era of pop art, op art, land art, performance art and many another avant-garde movement.

At primary school, in Germany in the 1920s, Freud was taught how to do up his shoes in a certain manner. So, he remembered eight decades later, I immediately thought Ill never tie them that way again. It was an entirely characteristic reaction. To be told he must do something, he has admitted, is enough to make him want to do something different. His unwillingness to follow the rules laid down has extended from fastening footwear to flouting the alleged dictats of art history.

Long ago, in reply to prognostications that his kind of painting which for want of a better word Ill call naturalistic was impossible, or irrelevant, after Czanne, or after Duchamp (art critics used to like to lay down these laws), LF said: I would have thought that the fact that something was forbidden, or almost illegal, would make it all the more exciting.

After about an hour, he suddenly flops down on a pile of rags in the corner, and asks if I want to stretch my legs. I take a look at the image that is just beginning to appear on the blank, white canvas. A glance at this charcoal drawing suggests he is planning an over life-size close-up of my head.

To pose for this, I wonder, will I have to cross my legs the same way every time? The answer is yes. LF says that weight and balance are affected by the position of the legs. So I am to spend dozens, maybe hundreds, of hours, with my right leg crossed over my left, and not the other way round.

How, I ask, does he decide to compose a picture?

I try to do something as little like what I have just done as possible. My ideal response from someone who saw a new work would be: Oh, I didnt realize that was by you.

We look at some drawings by Van Gogh, from the book I brought thinking I might pose as a reader. LF enthuses about one of an extensive landscape looking over the Crau, the plain outside Arles where Vincent often walked. Many people would say that this is derived from Japanese art, but I would happily exchange every Japanese landscape of the nineteenth century for this. It has such a wonderful sense of the earth, not just extending away towards the horizon, but also its curvature, its roundness.

Next page