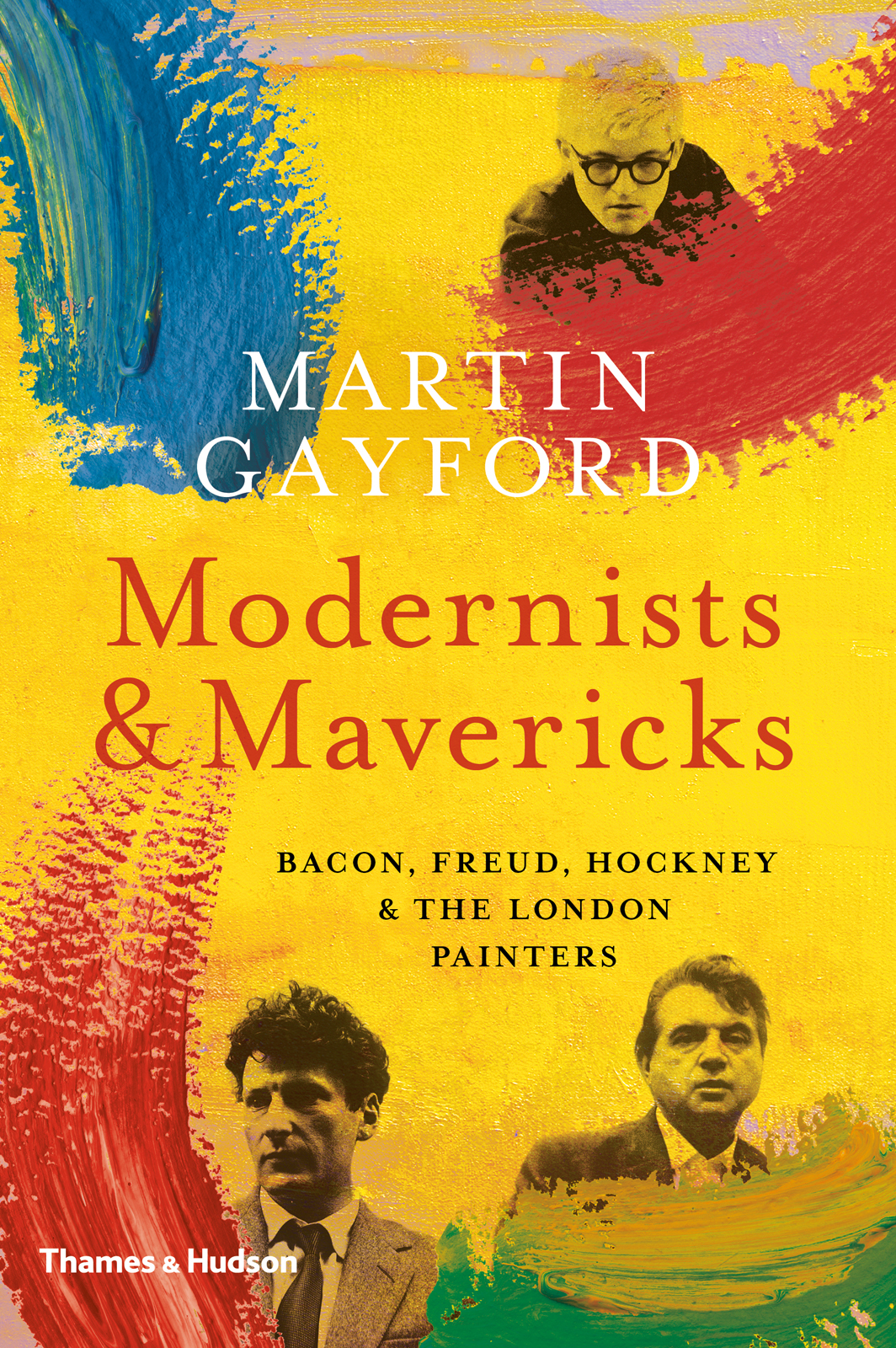

Timothy Behrens, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews at Wheelers restaurant in Soho, London, 1963. Photo by John Deakin

About the Author

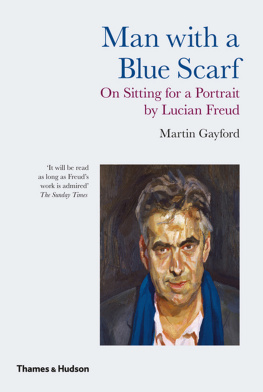

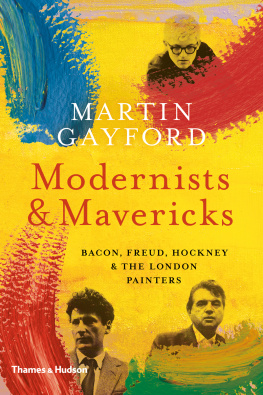

Martin Gayford is the art critic for the Spectator. Over the years, he has spent innumerable hours talking to artists, including many who feature in Modernists & Mavericks, and has had his portrait painted by Lucian Freud and David Hockney. His books include Man with a Blue Scarf, A Bigger Message and Rendez-vous with Art (with Philippe de Montebello) all published by Thames & Hudson. He is also the co-author with David Hockney of A History of Pictures.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Man with a Blue Scarf:

On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud

A Bigger Message:

Conversations with David Hockney

Interviews with Francis Bacon:

The Brutality of Fact

Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

O n the evening of 12 November 2013 Francis Bacons Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969) went under the hammer at Christies New York. After a lengthy bidding war, the work sold for $142.4 million (89.6 million). A picture painted in London well within living memory became, for a while, the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction.

This state of affairs would have been utterly unimaginable in 1969, when the picture was painted, let alone in the mid-1940s when Bacon and Freud first met. It would have stretched credulity even in 1992, the year in which Bacon died.

Of course, a price is just a number, and this one was perhaps a little freakish: an outlier. After all, few would claim that this triptych is even the greatest of Bacons works. Nonetheless, that such a record could be set at all makes a point: painting done in London in the decades after the Second World War has come to seem hugely more significant internationally than it did, for the most part, when it was being created.

Those twenty-five years or so, from about 1945 to around 1970, are the subject of this book. It is not written in the belief that the pictures produced within reach of the Thames were greater or more important than those made in New York, Rio de Janeiro, Delhi or Cologne. But, rather, that this was a fascinating time and place for painting and painters; and one that, despite being so close and in some ways familiar, is still little known.

For me, to speak personally, it has all the attractions and mysteries of the day before yesterday. At one time or another I have met and talked to many, indeed most, of the more prominent artists discussed in the following pages. Some have become good friends. With a few, I have spent uncountable hours in conversation. I was alive for some of the years covered in the chapters to come, though my interest in the contemporary art scene only came later. So, in a way, this is my investigation into what these fascinating people did before I encountered them.

Yet, even for participants, the past is a place that needs constantly to be recreated and re-examined. Talking about the late 1940s some sixty years later, Frank Auerbach one of the principal witnesses who have contributed to this text remarked: Im speaking here for a young man who no longer exists and of whom Im a rather distant representative. Something of the sort is true of all of us when we reach far back in time. Conversely, part of the art-historical attraction of this subject is that, unlike Cubist Paris, say, or Renaissance Venice, there is a plethora of first-hand testimony. Some of this is from people who have scarcely spoken about it before.

Modernists & Mavericks is, then, a collective interview, or multiple biography, that includes at least two generations and numerous individuals. In aggregate, this amounts to an archive of many thousand words, recorded over three decades. The book is drawn from interviews, often unpublished, with important witnesses and participants, including Frank Auerbach, Gillian Ayres, Georg Baselitz, Peter Blake, Frank Bowling, Patrick Caulfield, John Craxton, Dennis Creffield, Jim Dine, Anthony Eyton, Lucian Freud, Terry Frost, David Hockney, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, Allen Jones, John Kasmin, James Kirkman, R. B. Kitaj, Leon Kossoff, John Lessore, Richard Morphet, Victor Pasmore, Bridget Riley, Ed Ruscha, Angus Stewart, Daphne Todd, Euan Uglow, John Virtue and John Wonnacott.

This book was undertaken in the view that pictures are affected not only by social and intellectual changes, but also by individual sensibility and character. There was no historical inevitability, for example, about the advent of Francis Bacon. Indeed, his psychological and aesthetic constitution was so unusual, so strange in some respects, that it still remains difficult to comprehend. Yet without Bacon or the equally idiosyncratic contributions of Freud, Riley or Hockney the story that follows would surely have been quite different.

All histories have boundaries that are, to some extent, arbitrary. Time is a continuum; almost nothing starts or finishes neatly at a particular date. Books, however, often have to do so, if only to prevent them sprawling ad infinitum. The chronological parameters of this one from the end of the Second World War to the early 1970s correspond to notable turning points in British history, both political and cultural.

The first marked not only the end of hostilities, but also the advent of the Attlee government and the beginning of a long period of steadily, if slowly, increasing optimism and prosperity. The second turning point was less sharp but, nevertheless, the end of the 1960s signalled the conclusion of that era of hope and the start of a decade of crisis and decline.

In the arts, too, these were moments at which change occurred. After 1945 there was a great opening-up. A London art world that had previously been small and provincial turned its attention to what was happening elsewhere; at the same time, a much larger and wider group in terms of both gender and origins began to pour into the capitals art schools. The mid-1970s, in contrast, were an era in which painting of all kinds was out of fashion, neglected in favour of a variety of new media that included performance, installation and a radically redefined type of sculpture.

On the other hand, no single moment in art history represents a clean break. Several of the most prominent figures in these pages began their careers in the 1930s, including William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Bacon himself. Arguably several more, such as Freud and Gillian Ayres, produced their finest work well after the end point of the book. Some, Hockney and Auerbach among them, are energetically at work at the time of writing, still trying to outdo what they have done before.

In addition, the scope of Modernists & Mavericks is defined in two other ways: by place and by medium. Of course, the focus on London is not intended to imply that nothing important happened elsewhere in the United Kingdom, in Edinburgh, Glasgow or St Ives, for example; on the contrary, it clearly did. These are excluded because they were different centres, with their own stories. Consequently, when certain painters move as Patrick Heron and Roger Hilton did out of town, they also exit the narrative. Other talented individuals, such as Joan Eardley and Peter Lanyon, dont feature at all because their mature careers were spent far from London. Admittedly, I have followed certain individuals on journeys Bacon to St Ives, Hockney to Los Angeles my justification being that, in doing so, they remained London painters but, to use Hockneys phrase, on location.

Next page