About the Author

Martin Gayford is art critic for the Spectator and the author of acclaimed books on Van Gogh, Constable and Michelangelo. His volume of travels and conversations co-written with Philippe de Montebello, Rendez-vous with Art, and Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud are also published by Thames & Hudson. www.martingayford.co.uk

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Hockneys Portraits and People

Hockneys Pictures

Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters

Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud

Rendez-vous with Art

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

Introduction

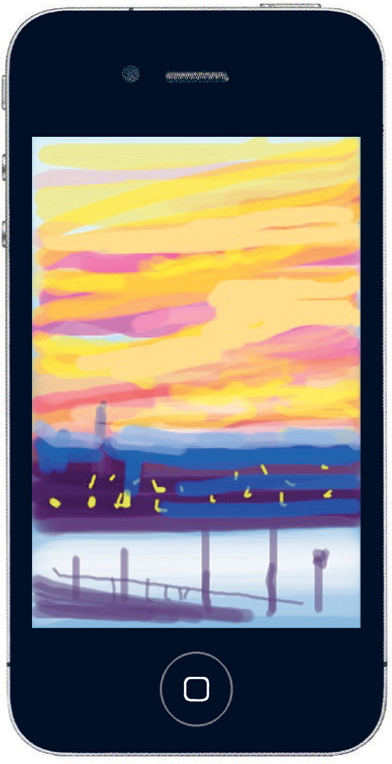

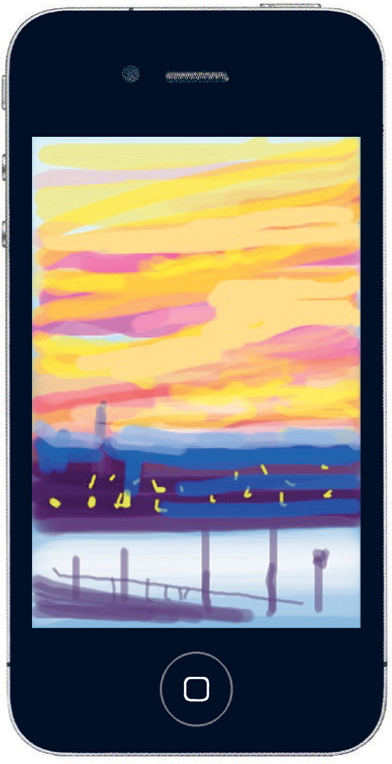

Turner with an iPhone

One morning in the early summer of 2009, I got a text from David Hockney: Ill send you todays dawn this afternoon. An absurd sentence I know, but you know what I mean. Later on it duly arrived: pale pink, mauve and apricot clouds drifting over the Yorkshire coast in the first light of a summers day. It was as delicate as a watercolour, luminous as stained glass, and as high-tech as any art being made in the world today. Hockney had drawn it on his iPhone.

The location of this sunrise was the north-east coast of England. For much of the early twenty-first century, Hockney lived in the seaside town of Bridlington, after having spent the previous quarter of a century based in Los Angeles. During the dark part of winter in East Yorkshire, the day length is short; in high summer, it begins to get light in the early hours of the morning. Hockney exulted in the early morning glory over the North Sea in another text (he is as fluent a texter as any teenager): Would Turner have slept through such terrific drama? Absolutely not! Anyone in my business who slept through that would be a fool. I dont keep office hours.

The text and the little dawn landscape were messages from Hockney, one verbal and one visual. He communicates by word and by image, and almost everything he has to say in each is worthy of attention. This is a book of conversations with the artist, discussions that have gone on now for a decade and a half, increasingly long and wide-ranging. The subject was usually pictures that is, man-made images of the world. He considered them from many points of view: historical, practical, biological, anthropological.

Untitled, 5 July 2009, No. 3, iPhone drawing

The earliest of our talks took place fifteen years ago; the most recent just a few weeks ago as I write. So the text is made up of layers a favourite word of Hockneys. He stresses the different washes that make up a watercolour, the coats of ink in a print, the strata of observation through time in a portrait. The words in these pages have accumulated in a similar fashion over months and years, exchanged by a variety of media old and new: telephone, email, text, sitting face to face talking in studios, drawing rooms, kitchens and cars. Many of the thoughts are Hockneys, but the arrangement is mine.

Its a series of snapshots of a moving object: what he has thought and said at many moments, and in various places. For most of this period, while Hockneys headquarters was in East Yorkshire, his interest was mainly directed towards depicting landscape in a multiplicity of ways. The last three chapters, however, track him after a double relocation: physically back to his old studio in California; and, in terms of subject matter, from outdoors to inside, from trees, plants and fields, to figures in interiors. There is a caesura in the text too. The first three quarters was completed at the beginning of 2011, the last portion over four years later, reflecting the changes of viewpoint and inner feeling brought by that interval of time.

*

Hockney tells an anecdote about a dinner party he once attended in Los Angeles. Another guest had posed a question: Are you a Constable or a Turner man? I thought, OK, whats the catch? So I asked her what the answer was. She said, Constable painted the things he loved, and Turner went in for spectacular effects. I said, But, Turner loved spectacular effects.

Hockney loves them too, but like Constable he returned to paint the landscape of his youth. Constable found many of his greatest subjects in his native village of East Bergholt in Suffolk. In the early twenty-first century, Hockney went back to the rolling hills of the Yorkshire Wolds, which he had first explored as a teenager. He drew them on paper, iPhone and iPad, painted them, and latterly filmed them simultaneously through nine high-definition movie cameras. This created another kind of spectacular visual experience, one never seen before in the history of art.

In other words, Hockney used very novel methods to tackle some of the perennial themes of art: trees and sunsets, fields and dawns. The problems of painting and drawing these things were familiar not only to Turner and Constable, but also to Claude Lorrain in the seventeenth century. Their challenges were Hockneys too: how can one translate a visual experience such as a sunrise a fleeting event involving expanses of space, volumes of air, water vapour and varying qualities of natural light into a picture? How do you compress all that into some flat coloured shapes on an iPhone or anything else?

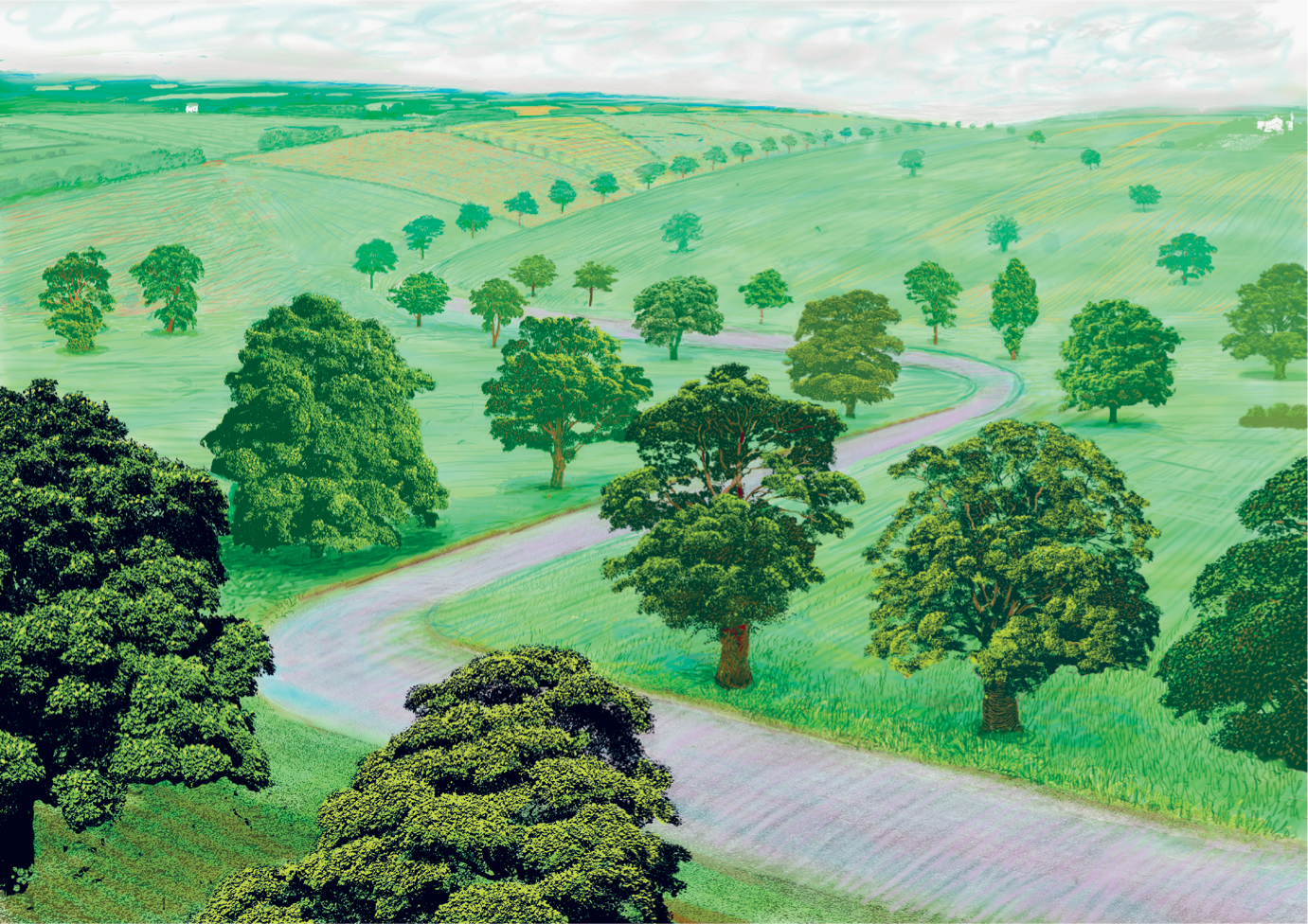

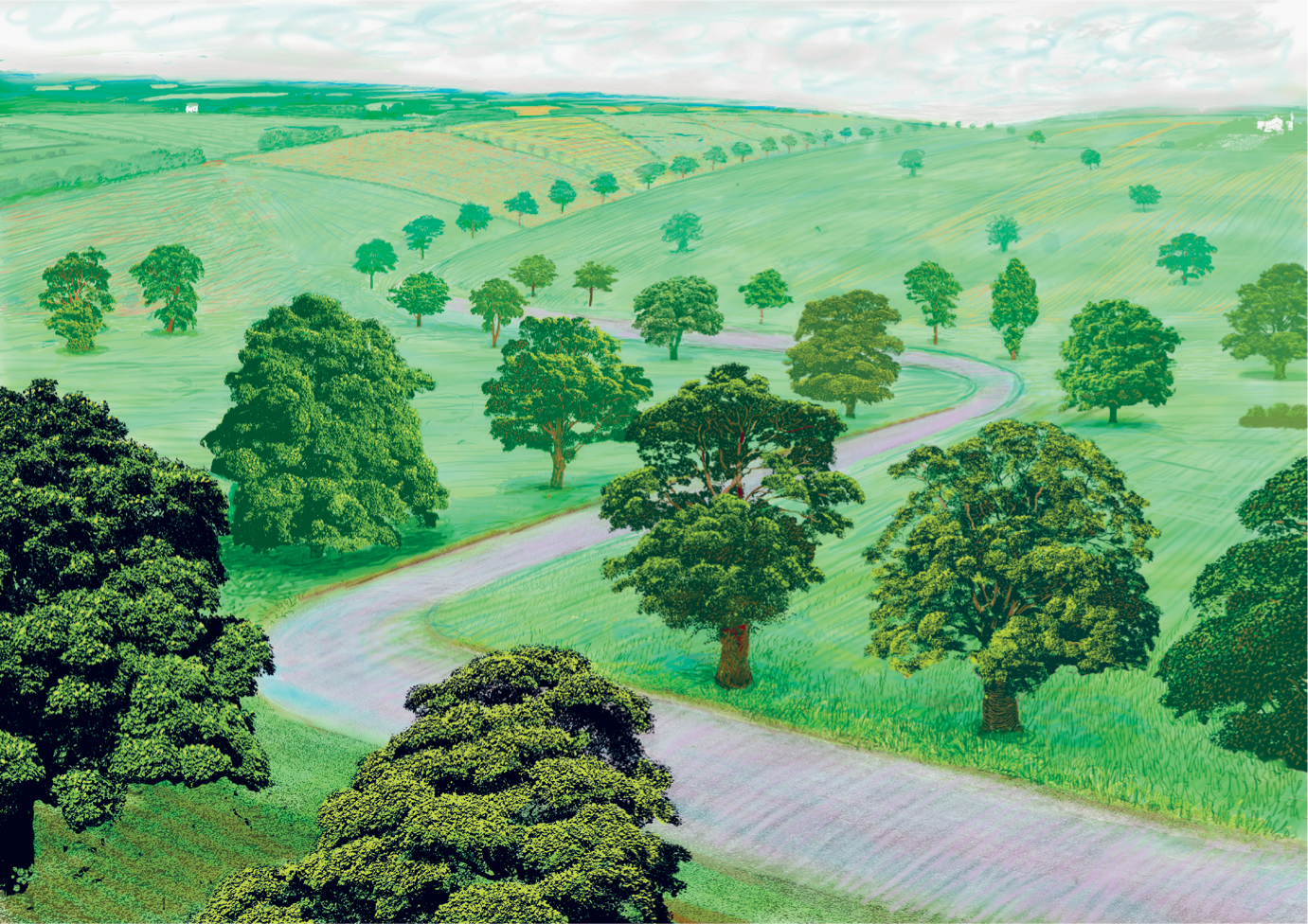

Green Valley, 2008

A picture, any picture, if you consider it for a moment, depends on several remarkable procedures. It stops time, or if it is a moving picture, it edits and alters time. Space is flattened. The subjective psychological reactions and knowledge of both the person who made it and the one who looks at it are crucial to the way it is understood.

The savants of the eighteenth century were much exercised by the question of what a person blind from birth, whose sight was suddenly restored, would make of the visible world. Amazingly, the experiment was actually performed. In the 1720s, William Cheselden, a London surgeon, removed the cataracts from the eyes of a thirteen-year-old boy. The latter gradually came to associate the objects he had known only through touch with what he now saw. One of the last puzzles he solved was that of pictures. It took two months, to that time he considerd them only as Party-coloured Planes, or surfaces diversified with Variety of paint. And that of course is exactly what pictures are, but they fascinate us and help us understand and enjoy what we see.

All good artists make the world around us seem more complex, interesting and enigmatic than it usually appears. That is one of the most important things they do. David Hockney is unusual, however, in the range, boldness and verve of his thinking. A while ago, he sent a book to a friend of his who was in prison in the United States. It was a thick History of Architecture by Sir Banister Fletcher, much thumbed and characteristically admired by Hockney for its beautifully lit photographs, but not intended as a work of reference. There was a long silence from Hockneys jailed associate. Then, eventually, there came a response. It turned out that in his cell he had been working through the entire tome from cover to cover and finally announced, Thats the first history of the world Ive ever read. Hockney was intrigued by this response and thought it over. In a way, he concluded, if its a history of the worlds buildings, it

Next page