MAIMONIDES Sherwin B. Nuland

JEWS AND POWER Ruth R. Wisse

THE EICHMANN TRIAL Deborah E. Lipstadt

WHEN GENERAL GRANT EXPELLED THE JEWS Jonathan D. Sarna

THE BOOK OF JOB Harold S. Kushner

ABRAHAM Alan M. Dershowitz

FORTHCOMING

JUDAH MACCABEE Jeffrey Goldberg

THE DAIRY RESTAURANT Ben Katchor

FROM PASHAS TO PARIAHS Lucette Lagnado

YOUR SHOW OF SHOWS David Margolick

MRS. FREUD Daphne Merkin

MESSIANISM Leon Wieseltier

Copyright 2016 by Masha Gessen

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gessen, Masha, author.

Title: Where the Jews arent : the sad and absurd story of Birobidzhan, Russias Jewish autonomous region / Masha Gessen.

Description: First edition. New York : Nextbook/Schocken [2016]

Series: Jewish encounters series. Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015049370 (print). LCCN 2015050024 (ebook). ISBN 9780805242461 (hardback). ISBN 9780805243413 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : Birobidzhan (Russia)History. Evreiskaia avtonomnaia oblasti (Russia)History. JewsRussia (Federation)Birobidzhan. BISAC: HISTORY /Europe/Former Soviet Republics. HISTORY /Jewish. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY /Literary.

Classification: LCC DK 771. B 5 G 47 2016 (print). LCC DK 771. B 5 (ebook). DDC 957/.7dc23

LC record available at: lccn.loc.gov/2015049370

ebook ISBN9780805243413

www.schocken.com

Cover illustration: Poster produced in the Soviet Union in 1929 by OZET (Organization of Jewish Land Workers) to advertise a fund-raising lottery to support Jewish migration to Birobidzhan. Text, from top to bottom: We will finish with the old more quickly if we participate in the OZET lottery. Every OZET lottery ticket bought will increase the number of Jewish agricultural laborers. To the green news shoots of the laboring fields. Photograph of poster by Buyenlarge / Getty Images.

Cover design by Kelly Blair

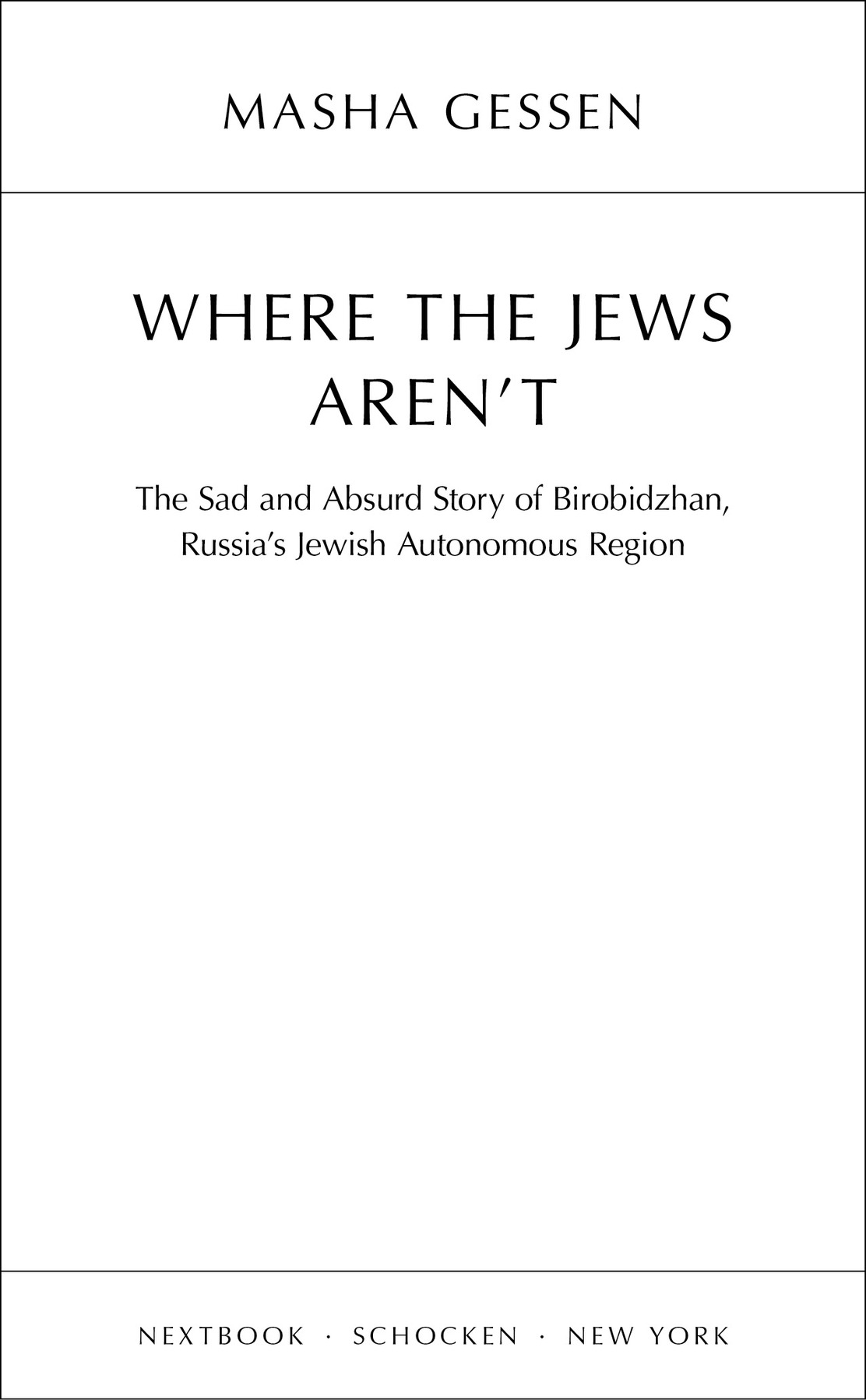

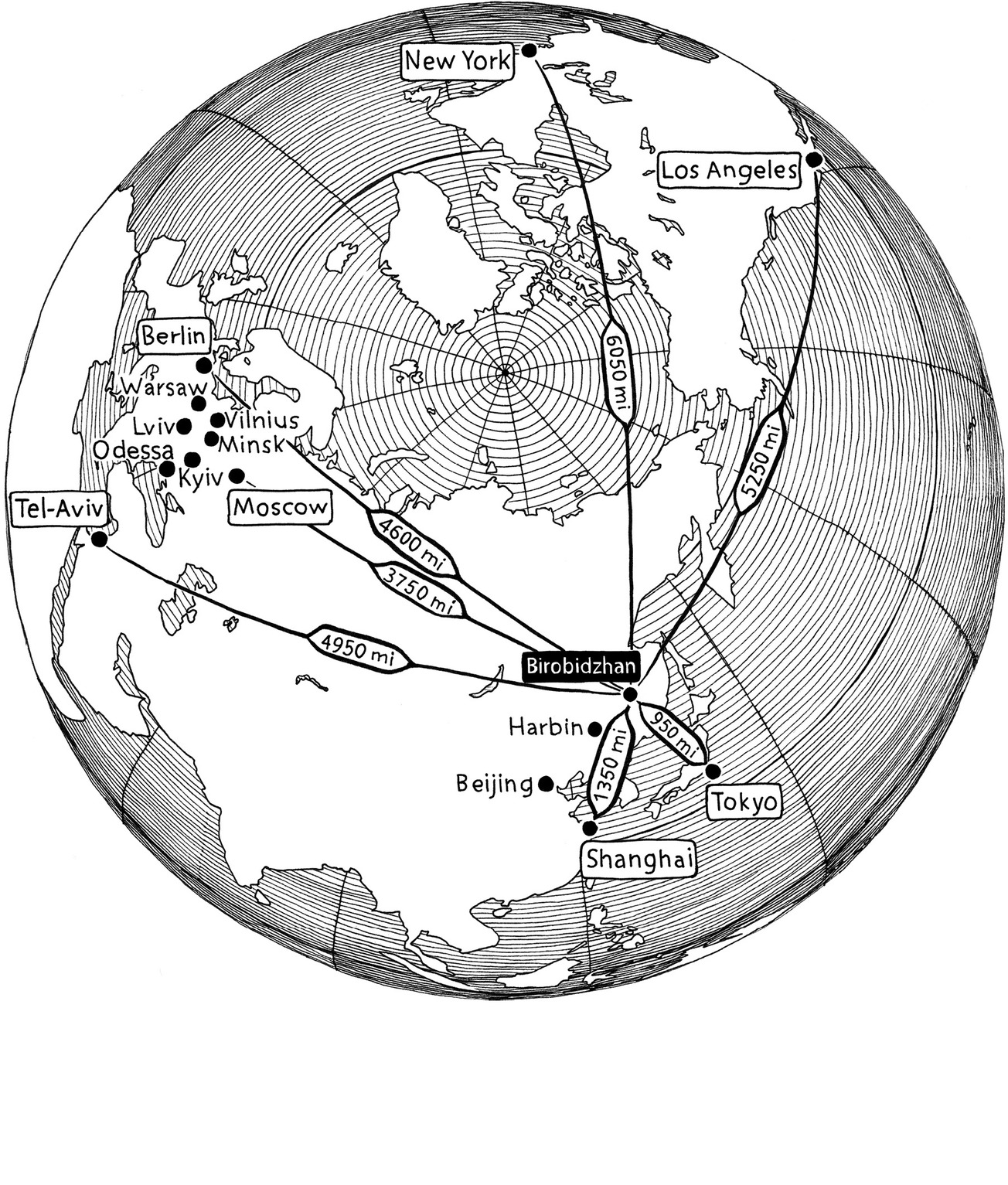

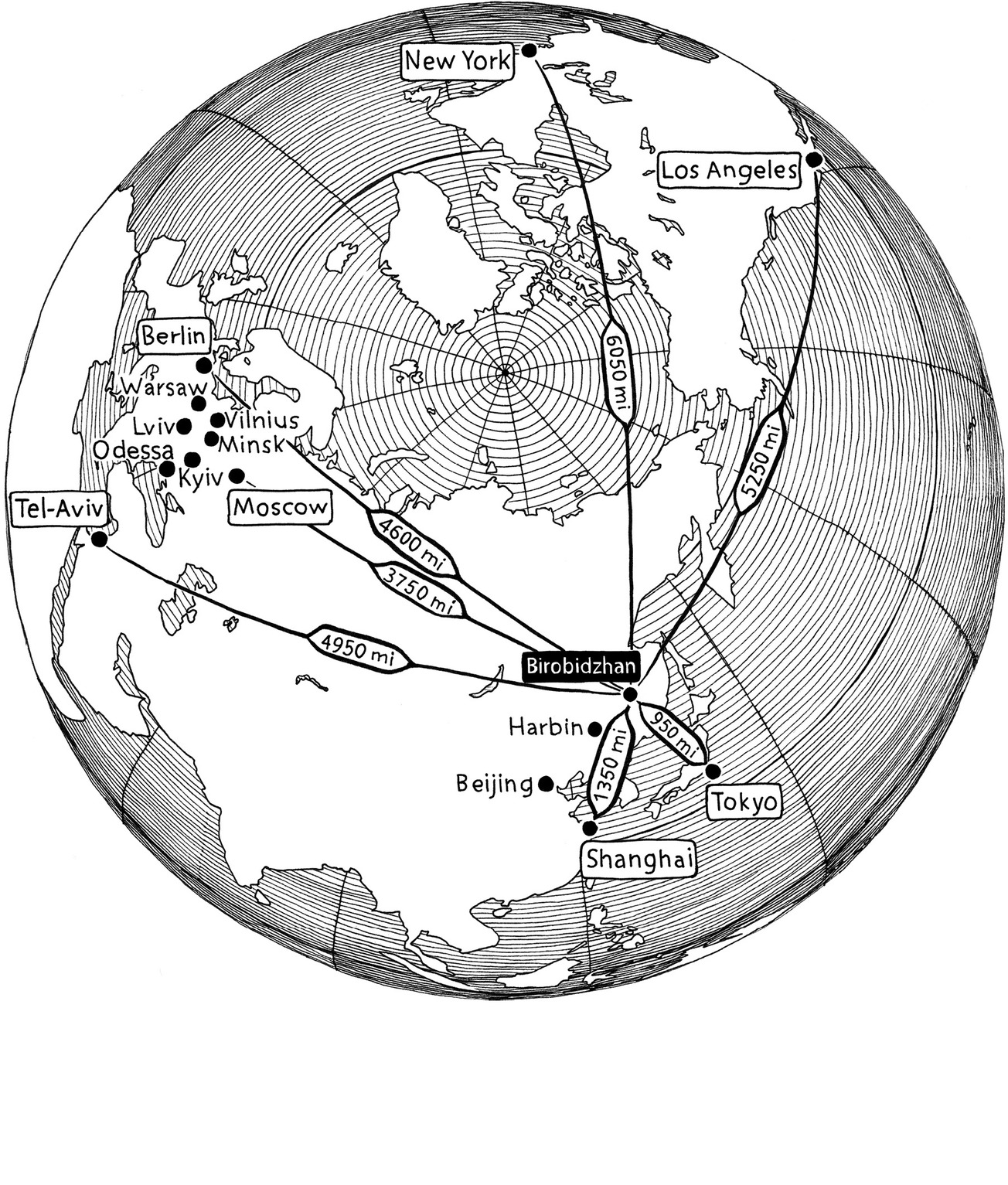

Infographic on endpapers and map on by Darya Oreshkina.

v4.1

ep

Contents

To my parents, who had the courage to emigrate

And thus have I been sitting for so long at the gate of this city, into which no one enters and from which no one leaves.

Everything I once knew I have now long forgotten, and in this mind of mine nothing more than a single thought remains:

All, all have long since died, and I alone am alive, and no longer await anyone.

And when I look above me once more, and feel the power and might that sleep in me, I no longer even sigh, but simply think:

I am the guardian of a dead city.

DAVID BERGELSON , Nokh Alemen (When All Is Said and Done)

PROLOGUE

A t the age of twelve I sat on the floor and had what felt like the most important conversation of my life with my best friend, who was mostly silent. I sat on the floor because I had been ambushed by puberty and now towered over my friend when standing. He was the other Jewish kid on the block, so we had been inseparable for years. There used to be two other Jewish children our age living one block over, in another nine-story, twelve-entrance concrete apartment monolith. One of those kids had disappeared about a year earlier, and his friend, the other one, told us in a hushed, serious voice that the kid had emigrated to Israel.

I sat on the floor because doing so underscored the dramatic bareness of the room. The apartment had felt desolate and barely inhabited for the last six months, since my parents had shipped all our books to America. After filing our exit-visa application with the appropriate authorities, they had spent night after night at the kitchen table poring over two different world atlases, letters from friends who had emigrated long ago, and assorted magazineschoosing their destination, under the yellow light of a kitchen lamp, in the dark. Except for one recent trip to Poland, they had never been outside the Soviet Union; the world seemed too large and too silent for them to make a choice. Finally, citing friends, purported job opportunities, and a familiar climate, they settled on Bostonand shipped all our books there.

This is crazy, I said to my best friend. Why leave one place where Jews are in a minority, only to go to another? He listened uncomfortably. His parents had opted to stay in the Soviet Union. This choice had opened a chasm between us. My friend and I, our parents, the parents of the kids from the other block, all of our extended families going back for centuriesour peoplehad been engaged in an ongoing argument. When should the Jews stay put and when should the Jews run? How do we know where we will be safe? Does departure ever signal cowardice? Can the failure to leave be a betrayal of life itself? There is only one right answer to any given question at any given time. If you get it wrong, you may pay with your life.

Before applying for an exit visa, my parents had spent six years arguing about emigrationin the way in which they argued: my mother cajoled my father, reasoned with him, and screamed at him, and he played stone stubborn. My mother argued that it was necessary for my future: if we stayed in the Soviet Union, I would not be admitted to university. In their preoccupation with my imaginary college career in the United States or the USSR, my parents were oblivious to the fact that in grade school I had been beaten almost daily for being Jewish and in middle school I was ostracized and feared, because I had learned to fight back. When I was eight, my brother was born and my parents turned to arguing about whether they had to emigrate for both of our futures. In 1978, when my brother was three and I was eleven, they made the calland we all finally landed on one side of the debate. From here, the people who were staying looked lost. But I thought my parents were acting foolhardily, too: I was sure that the only place we could be safe was Israel.