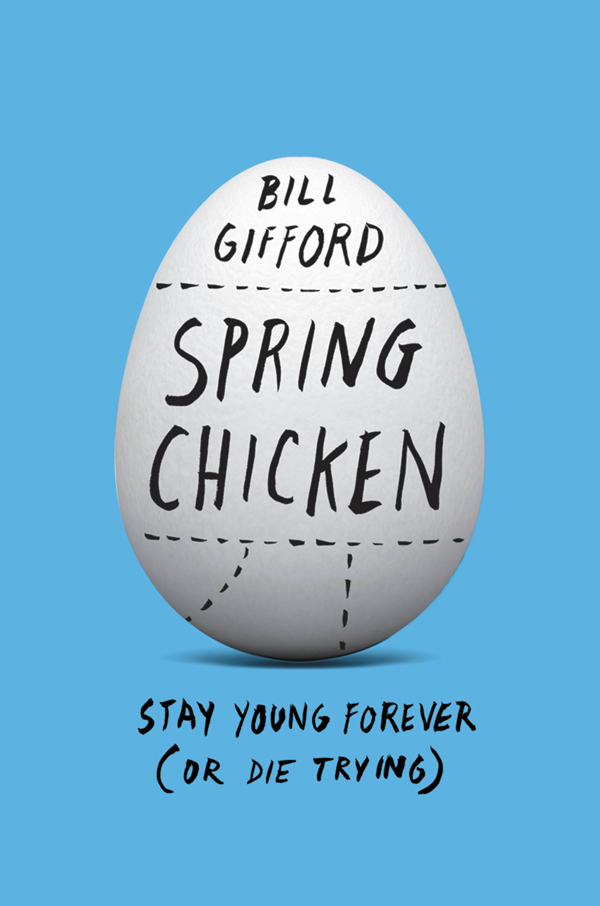

Cover copyright 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

I think the most unfair thing about life is the way it ends. I mean, life is tough. It takes up a lot of your time. What do you get at the end of it? A death! Whats that, a bonus? I think the life cycle is all backwards. You should die first, get it out of the way. Then you live in an old age home. You get kicked out when youre too young, you get a gold watch, you go to work. You work for forty years until youre young enough to enjoy your retirement! You go to college, you do drugs, alcohol, you party, you have sex, you get ready for high school. You go to grade school, you become a kid, you play, you have no responsibilities, you become a little baby, you go back into the womb, you spend your last nine months floatingand you finish off as a gleam in somebodys eye.

Sean Morey

You are never too old to become younger.

Mae West

I n his final moments of consciousness, as the young scientist crumpled to the laboratory floor, he may have realized that perhaps covering himself with varnish was not the best idea he had ever had, experiment-wise. But he was a man of science, and curiosity could be a cruel mistress.

He had been wondering for a while about the function of human skin, so durable and yet so delicate, so sensitive to burns from sun and flame, and so easily sliced open by knives much less sharp than his surgeons blades. What would happen, he wondered, if you covered it all up?

So, on what was otherwise a slow day at the lab, at the Medical College of Virginia in genteel Richmond, Virginia, in the spring of 1853, Professor Charles Edouard Brown-Squardnative of Mauritius, citizen of Britain, late of Paris (via Harvard)stripped off all his clothes and went to work on himself with a paintbrush and a pail of top-quality flypaper varnish. It didnt take long before he had coated every square inch of his naked body with the sticky liquid.

This was still an era when a scientists primary guinea pig was generally himself. In one experiment, the thirty-six-year-old Brown-Squard had lowered a sponge into his own stomach to sample the digestive juices within, which caused him to suffer gastric reflux for the rest of his life. Such practices distinguished him as by far the most picturesque member of our faculty, as one of his students would later recall.

The varnish episode would only add to his legend. By the time a random student happened to stumble across him, the professor was huddled in a corner of his lab, trembling and apparently near death. His body was so brown that it took a moment for the student to realize that he was not a wayward slave. Thinking quickly, the young man frantically began to scrape off the brown gunk, only to receive a tongue-lashing from the victim, who was furious that some obtrusive individual [had] extracted him from the corner into which the varnish had tumbled him, and, just as he was fetching his last gasp, maliciously sandpapered him off.

Thanks to that quick-witted medical student, though, Brown-Squard would go on to become one of the greatest scientists of the nineteenth century. Today he is remembered as a father of endocrinology, the study of glands and their hormones. As if that were not enough, he made major contributions to our understanding of the spinal cord; a particular type of paralysis is still called Brown-Squard syndrome. Yet he was far from an ivory-tower academic. He once spent months battling a deadly cholera epidemic on his native Mauritius, a lonely archipelago in the middle of the Indian Ocean. True to form, he intentionally infected himself with the disease by swallowing the vomit of patients, in order to test a new treatment on himself. (That nearly killed him, too.)

His Richmond professorship did not last the year; the Frenchmans eccentric ways and darkish skin proved too much for the Southern capital, so he moved back to Paris, to spend the remainder of his career shuttling between France and the United States. All told, he spent six years of his life at sea, which would have made his late sea-captain father proud. Yet despite his near-constant state of motion, he could not outrace old age. By his sixties, Brown-Squard had fetched up once more in Paris, as a professor at the Collge de France. His friends included Louis Pasteur, as in pasteurization, and Louis Agassiz, one of the forefathers of American medicine. The poor orphan from far Mauritius was inducted into the French Legion of Honor in 1880, followed by a slew of other prestigious prizes, culminating with his election as president of the Socit de Biologie in 1887, confirming his status as one of the leading men in French science.

He was seventy years old by then, and he was tired. Over the previous decade, he had noticed certain changes overtaking his body, none of them good. He had always buzzed with frenetic energy, bounding up and down stairs, talking a mile a minute, then interrupting himself to scribble down his latest brilliant idea on the nearest scrap of paper, which would vanish into a pocket. He slept just four or five hours a night, often beginning his workday at his writing desk at three in the morning. It has been suggested, by his biographer Michael Aminoff, that he may have been bipolar.

But now his once-boundless vigor seemed to have abandoned him. He had evidence, too, because he had long kept track of his body, measuring things like the strength of his muscles and keeping careful records. In his forties, he had been able to lift a 110-pound weight with one arm. Now the best he could do was eighty-three pounds. He got tired quickly, yet he slept poorly if at all, and he was tormented by constipation. So naturally, being the scientist he was, he decided to try to fix the problem.