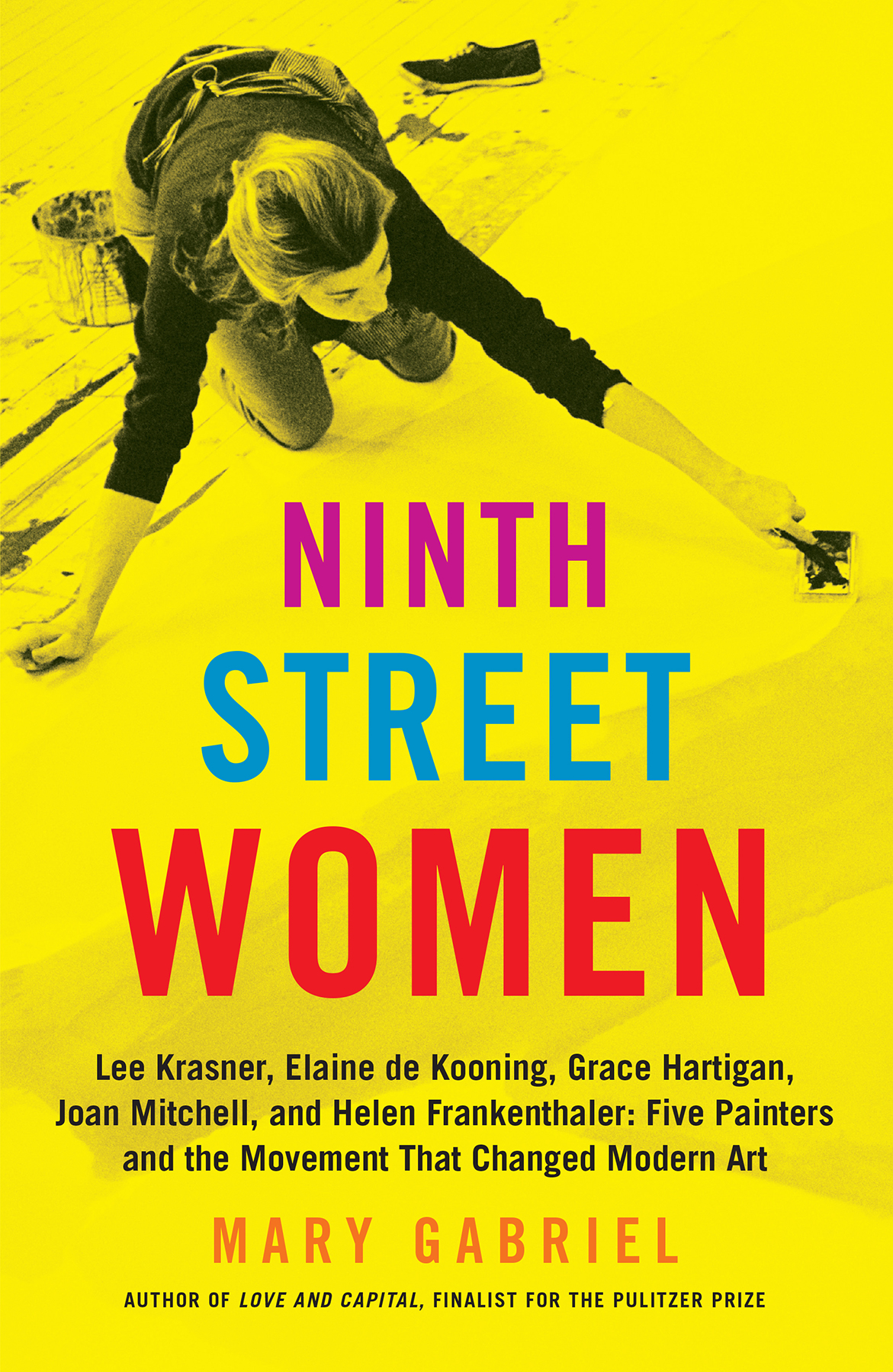

T HE IDEA FOR this book arose out of a conversation I had with painter Grace Hartigan in the fall of 1990. At sixty-eight, she was in the midst of her biggest year in decades, with multiple exhibitions scheduled and a monograph of her work newly released. The publisher of the art magazine where I worked decided that all this activity warranted a feature, which she asked me to write. It was an assignment I approached with trepidation. I had known of Grace for years; she was the head of the graduate painting program at the Maryland Institute College of Art while I was an undergraduate. From a safe distance, I had watched terrified as she walked, blond and imperious, ahead of a gaggle of eager students, held forth loudly amid rapt listeners at the Mount Royal Tavern next door, and delivered withering critiques as she toured classrooms and studios. From my student perspective, she was a tough old bird who I imagined had had to fight throughout her career against art world prejudices that viewed a womans art as womens work (inherently lesser) and that, having endured such systematic debasement, she was not inclined toward magnanimity. I therefore rang the bell at her Baltimore loft braced for an hour with an impatient, dismissive diva. Of greatest interest to me as I waited on the street below was how many minutes would pass until I could return there.

And then Grace opened the door.

The woman who greeted me warmly and generously was utterly disarming. She bore no resemblance to the person I had grown to fear. Confused and smitten, I followed her up the many flights to her studio, where we sat as our one-hour interview stretched into four, as the light through her massive windows faded from gold to gray, as the story she told stirred my imagination and changed my life. I was in the presence of a woman who had sacrificed everything, including her only child, to be what she was: an artist. The rewards had been few, beyond a life well lived (not materially, but spiritually) and the recognition in her waning years that she had been honest about who she was and what she needed. A rare accomplishment for a woman of any generation, it was particularly so of hers, when servitude to family was the only goal toward which a healthy woman was to aspire. Grace was living proof that, on the contrary, a life dreamed could be a life lived. All it took was courage, commitment, and humor. I remember both of us laughing a lot that afternoon. Though the subject was serious, the stories Grace told were fantastic and the woman who recounted them was as wild as the twenty-six-year-old who had abandoned everything in 1948 to paint, though she wasnt even sure how.

Grace was part of the art movement born in New York in the 1930s that shifted the capital of Western culture from Paris to New York, and changed the very history of art. It was nothing short of a revolution and, like every revolutionary endeavor, it was peopled with an assortment of talented, brilliant, and mad visionaries who existed, initially, so far outside society that they were invisible to everyone but each other. She described the people she counted as friendsmen and women, straight and gay, writers and painters and composerswho survived and thrived during the most turbulent two decades of modern U.S. history and amid a society so timidly conservative that its greatest ambition was conformity. Grace and her friends were outlaws in that world, joyfully upending every tradition that presented itselfartistic and socialand in the process creating a new way of painting, sculpting, writing, and composing that shaped the standards by which we still make and appreciate art today. But Graces stories went beyond the sweeping importance of the movement. She described the intimate struggles endured and victories achieved by people who became legend and, almost more interestingly and significantly, people long forgotten who were nonetheless vitally important to their peers. In each of those stories, because Grace spoke of friends, the trials and triumphs felt immediate. Art wasnt removed from life, it was life.

I had never encountered art history as stirring. Paintings I had only half understood now came alive because I felt I had met, if only figuratively, the artists who made them. I began to understand the cross-pollination between painting and music, or painting and poetry, through Graces myriad tales of the writers and composers she knew and loved. And I recognized the necessity of understanding the times in which Grace and her fellow artists lived. They did not create in a vacuum, as those who rely on theory to explain art often imply. They had not expunged all recognizable imagery from their work on an aesthetic whim or to coldly advance the progression of modern art begun in the previous century. They stripped their work of all life except their own internal meanderings because they existed in a world destroyed by war, dehumanized by the death camps, and denied a future by the atomic bomb. Under those circumstances, what else could they paint with any degree of honesty?

As Grace spoke, she didnt dwell on the fact that she was a woman artist or that other women formed an important part of the Abstract Expressionist group. But each time she mentioned a woman painter or sculptor, I found myself wondering why, in the official history, those names so rarely surfaced. Their contributions were significant. In fact, in the cases of Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning, the movement would not have existed or unfolded as it did without them. And yet, the story of that movement has been taught and accepted as the tale of a few heroic men.

There are many reasons for that interpretation, some endemic to the history of art, in which man is traditionally the creator and woman the muse, and some specific to America at mid-century. Prior to the Abstract Expressionists, Americans generally mistrusted male artists (female artists werent even worth discussing) and labeled them as effete or elitist. The New York crowd, beginning in the 1930s, was the first generation to make painting and sculpture an American manly occupation. The movements macho character was, therefore, part and parcel of the transformation it initiated. But another important reason the Abstract Expressionist story has belonged to men involves something much more insidious: the market. When art became a business in the turbocharged consumer economy of the late 1950s, work by women artists wasnt considered as valuable as that of men, which meant dealers didnt show it, magazines didnt write about it, collectors didnt buy or donate it to museums, and art history courses failed to mention it. Gradually, most of the women who were part of the Abstract Expressionist movement were at best sidelined and at worst forgotten, despite the fact that they had been heralded before the art business took control of the art world and that they were pioneers, breaking down centuries-old cultural and social barriers.