Oxford Cultural Biographies

Series Editor

Gary Giddins

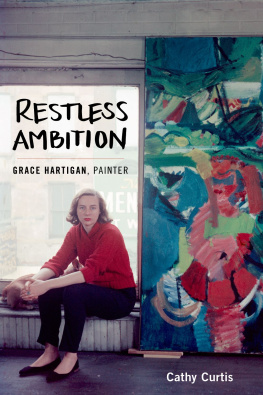

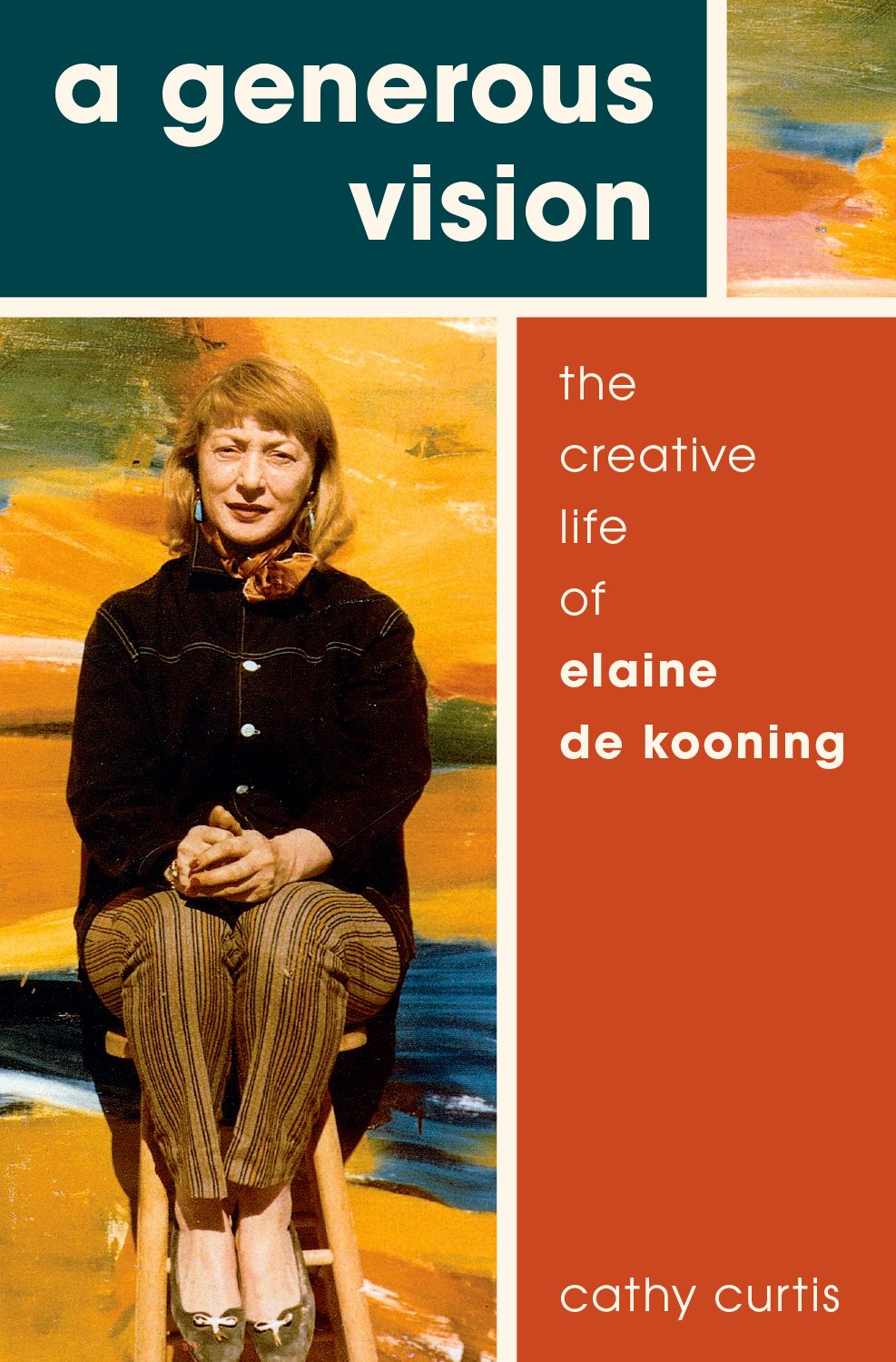

Cathy Curtis

A Generous Vision:

The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Cathy Curtis 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Curtis, Cathy (Writer on art), author.

Title: A generous vision : the creative life of Elaine de Kooning / Cathy Curtis.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2017. | Series: Oxford cultural biographies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017016260 | ISBN 9780190498474 (cloth : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9780190498504 (oxford scholarship online)

ebook ISBN 9780190498498

Subjects: LCSH: De Kooning, Elaine. | PaintersUnited StatesBiography. |

Women paintersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC ND237.D3339 C87 2017 | DDC 759.13 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017016260

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

To Svetlana Alpers, professor emerita, University of California, Berkeley, who introduced me to close looking and independent thinking

Contents

one need not be a lawyer, only a veteran of courtroom TV shows, to know that nothing rouses a jurist to bellow Objection! like an attempt by opposing counsel to indulge in hearsay testimony. Yet hearsay provides the primary texture of way too many biographies, where uncorroborated, unsourced scuttlebutt is casually asserted as fact to fill in blanks or enliven a narrative. Cathy Curtis is, of course, not that kind of biographer, and her A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning is admirable not least in its refusal to pass off a good yarn as history or adjudicate conflicting accounts with Voice of God certainty. Interviews are habitually freighted with hearsay, but in weighing, balancing, and pinpointing her choir of sources, Curtis earns and keeps the readers trust. As the first biographer of an artist long relegated to the category of great mans wife, she has a unique perspective from which to traverse a much-chronicled time and place. At center stage is a subject so personably large and stubbornly anarchicnot to mention artistically undervalued and deserving of serious reconsideration in her own rightthat she exerted undeniable gravity in her world and leaps off the page into ours.

Curtis begins with a brief preface, enumerating the standard biographical tools that were not at her disposal: an unfinished memoir, journals and notes that seemingly disappeared, lost or unavailable correspondence. Nothing daunted, she weaves her story out of a comprehensive mastery of previously published works amplified by exhaustive original research, which included the judicious perusal of de Koonings often overlooked critical writings. Despite a few major exhibitions of her paintings in recent years, Elaine de Kooning has been treated rather shabbily by critics and historians of her era, who recall her more for her extravagances than her talent. A Generous Vision is a necessary corrective, refocusing our attention on her as artist, writer, and teacher.

Is this a feminist biography? You bet. Curtis is particularly sensitive to the rules and assumptions of sexual power. From early childhood, Elaine Fried refused to be defined by gender expectations; when she married Willem de Kooning, at a time when he could barely finalize let alone exhibit a painting and each dollar had to be allocated to paint, food, or rent, she brooked no condescension from him or anyone else. Before she published and long before she established her domain in portraiture, she alluringly shouldered her way into the world of downtown artists, whether it meant the Club (which previously barred women) or Cedar Tavern. Esteban Vicente remarked, No one could keep [Elaine] out of anything she wanted to be part of. She made her mark at Black Mountain, although she attended as wife and student. She was as adept as the men at musical beds, perhaps more so, since the men usually contented themselves with nubile worship, while she took lovers who could and did influence the art world on behalf of herself and her husband. She could be an indifferent, uncaring, and callous wife, but she always kept faith with her muse. Willem expected her to stop painting when they got married, and when he asks her to support them, she responds, I never ask you to get a job. Dont ask me. I want to paint as much as you do, and Im willing to starve along with you.

De Kooning was an incisive critic and an influential teacher, but it is through her paintings that she has the most to say to posterity. Not surprisingly, this book is especially stimulating in passages that allow us to see how she worked. She is best known for her portraiture, a field in which she occupies a singular middle ground between formalist representation and caricature. Her use of abstract expressionist techniques to elucidate familiar images helped to make those techniques accessible to the general public. At the same time, she pioneered a redefinition of the female gaze. Curtis alerts us up front that de Kooning demanded the freedom to paint the opposite sex as sex objects. Her most celebrated portrait is that of President Kennedy, and Curtis has dramatized this fascinating episodethe commission, the process (At one point I had thirty-six canvases going at once, all different stages, de Kooning recalled), and the denouementwith copious and telling details. She is equally absorbing in describing the genesis and realization of de Koonings splendid basketball paintings, a process that began with the artists epiphany that grainy black-and-white newspaper photos, seen from a distance, are like abstract compositions, freeing her to invent her own color schemes and to infuse pure action with a sense of the tragic. When de Kooning first saw the prehistoric paintings in caves at Niaux and Bdeilhac, she remarked on the fantastic courage it must have taken for those first artists to go into the caves. A Generous Vision encourages us to consider the courage of Elaine de Kooning.

Gary Giddins, Series Editor

everyone knows that the painter Willem de Kooning was one of the titans of twentieth-century art. But few people realize that his wife, Elaine de Kooning, was a prime mover among New York artists at mid-century. Elaine was an incisive writer who pinpointed the essence of painters as dissimilar as Franz Kline and Auguste Renoir, and deftly refuted pompous critical rhetoric. She was a celebrated portrait painter whose sitters included leading artists and writers in her circle and (most famously) President John F. Kennedy. Her fascination with people and animals in motion led her to paint subjects as diverse as bullfighting, basketball, Paleolithic cave paintings, and a multi-figure sculpture in the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris.